TRACCE no. 8 – by Grant S. McCall

Following Tracks (Namibia). In the country of Namibia, in southern Africa, one may find one of the most dense occurrences of rock art in the world.

Within one hundred miles of one another lie three of the most important sites in the entire world.

Within one hundred miles of one another lie three of the most important sites in the entire world.

These are the paintings in the Brandberg, the engravings and paintings at Twyfelfontein, and the engravings at Piet Alberts Kopjes. Of these three sites, the most impressive must be Twyfelfontein. Twyfelfontein is certainly the most prolific occurrence of rock engravings in the world. The current estimate numbers the engravings there at more than two thousand (which I believe to be very conservative).

The quality of the engravings is no less remarkable. Twyfelfontein also is a rare example in southern African rock art of paintings and engravings occurring at the same site. Indeed, in one case there, they even occur in the same shelter. But with all that could and has been examined at Twyfelfontein, the author chooses to look at a common, seemingly nondescript theme that inhabits the engravings of Twyelfontein, which has been misinterpreted for decades now.

At Twyfelfontein, a very common theme is the depiction of the tracks of certain animals. An engraved track can be associated with nearly every variety of animal common to the region. Predictably, these tracks can be observed in the engravings at Piet Alberts Kopjes, as well. In addition to depiction of lines of spoor, there are also animals depicted with tracks affixed to their legs. The interpretation of these tracks has always been so astoundingly simple that most texts do not even bother with their mention.

To most scholars, it has always been assumed that the tracks were something of a school book, or a way of teaching children which track belonged to which animal.

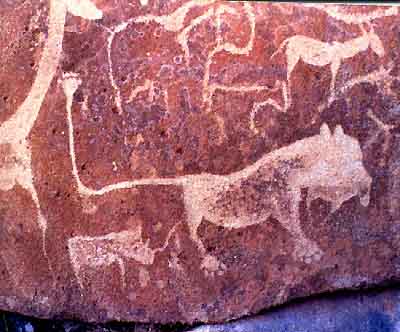

Tracks from Twyfelfontein

This is a collection of tracks from Twyfelfontein. Giraffe, eland, lion, and springbok tracks are easily seen in this picture.

There are a few troublesome aspects to that idea, however. There are dozens of depictions of the tracks of every variety of animal. Why would the artist expend so much energy on engraving multiple sets of tracks for a given animal? One set would certainly suffice for instructional purposes. In addition, while many of the tracks are rendered so precisely that one can easily distinguish between even very similar species of antelope, many tracks are depicted unrealistically.

For instance, there are several examples of five-toed creatures depicted with six or more toes. This would not encourage an accurate knowledge of tracking amongst the tracker-in-training. The last qualm arises from an interview the author had with a bushman shaman at his village outside Tshumkwe, in Bushmanland.

The shaman indicated that, in his band at least, such a knowledge of tracking would acquired by observing more experienced trackers. When introduced to him, the concept of a formal educational system suggested for the tracks at Twyfelfontein seemed entirely foreign.

While many aspects of culture differ immensely from one band of bushmen to the next, the author believes this lack of formal instruction to be common to all bands, past and present. The degree of formality and rigidity implied by this idea is simply not natural to the hunter-gatherer bands that left them. The better interpretation is more complicated. J.D. Lewis-Williams reports a painting elsewhere with similar tracks trailing behind, perhaps left by, a large therianthrope.(1) Similarly at Twyfelfontein, there are several occurrences of animals that appear actually to be shamans in animal form with tracks affixed to their legs.

Lewis-Williams also reports many depictions of shamans holding the foreleg of an antelope, one would assume with intent to produce tracks with it (2) Bert Woodhouse reports many therianthropes with clearly defined hooves. (3) A remarkable example of this is found just forty miles from Twyfelfontein in the Brandberg at Maack’s Shelter. There are several clear depictions of shaman in a therianthropic form, with hooves clearly visible. It would seem that the tracks are in some way associated with shamans in the form of animals.

Therianthrope from Maack’s Shelter

This is a therianthrope from Maack’s Shelter. I argue that is a shaman with the front features of a hartebeest, involved in a game-controlling activity. Note the clearly defined hooves on the forelegs.

Lion from Twyelfontein

This is a lion from Twyelfontein, with tracks affixed to its legs. I argue that this is actually a shaman in lion form. Note the line extending from the lion to the rhino, indicating that the rhino is being led by the lion.

Lewis-Williams suggests that making tracks in the manner mentioned above is an attempt to supernaturally control game animals.(4) He supposes that a shaman could affect the wanderings of game by leaving tracks for the herds to follow.(5)

This idea seems absolutely correct with respect to the engravings of spoor at Twyfelfontein and Piet Alberts Kopjes. The therianthropic shamans at Maack’s Shelter are clearly attempting to entice the game also depicted to follow them.

At Twyfelfontein, there are several depictions of what seem to be shamans leading game. This is often denoted at Twyfelfontein by a line extending from the shaman to the game animal. In one case, such a line extends from a track directly to a game animal. This implies that, as Lewis-Williams theorized, the animal was attracted by the track. Thus, the tracks at Twyfelfontein are related to this practice of supernaturally controlling game movement by leaving tracks for the game to follow.

Zebra from Twyfelfontein

This is a zebra from Twyfelfontein. Note the line extending from the track on the right to the zebra. Some have argued that this indicates the track belongs to the zebra, but it is another variety of track, not belonging to a zebra. I argue that the line indicates that the animal is being attracted by the track.

Thus, in this case the simple explanation was false. Many themes in rock art such as the one discussed are foreign to our sensibilities as modern folk. What seems to the modern viewer to be a very backward meaning for the tracks would have been immediately comprehensible to the hunter-gatherer shamans who understood the practice. As modern researchers, what seems the simplest interpretation is doomed to exude facets of the modern world. It is all a modern viewer knows.

Obviously, the ancient bushman shaman artist would have had no concept of a modern convention such as a school book. Conversely, a modern viewer would have only peripheral knowledge of a practice such as supernaturally leading game by leaving a track for the game to follow.

Because of this incompatibility in culture, what seems the simplest interpretation is clearly incorrect. As researchers, we must reject the simple, and instead turn to the logical intepretation for our interpretations.

Grant S. McCall

http://www.geocities.com/Athens/Forum/3339/rockart.html

Notes

- Lewis Williams, J.D. – Dowson T., 1989.Images of Power. Southern Book Publishers, Johannesburg, . 102.

- Lewis Williams – Dowson, 102-103.

- Woodhouse B., 1979.The Bushman Art of Southern Africa. Purnell & Sons, Cape Town, 90.

- Lewis Williams – Dowson, 102-103.

- Lewis Williams – Dowson, 103.

Leave a Reply