TRACCE no. 10 – by M. Leigh Marymor

Looking Back at Four Years of Advocacy for the Ring Mountain Petroglyphs – California (USA).

In the Fall of 1993, the Bay Area Rock Art Research Association (BARARA) began an effort to insure protections for the Ring Mountain petroglyphs in Tiburon (Marin County), California .

In the Fall of 1993, the Bay Area Rock Art Research Association (BARARA) began an effort to insure protections for the Ring Mountain petroglyphs in Tiburon (Marin County), California. Exactly four years later, after countless hours of planning, community organizing and bureaucratic cajoling, the Ring Mountain petroglyphs enjoy a new hope for a future free from unintentional damage and vandalism.

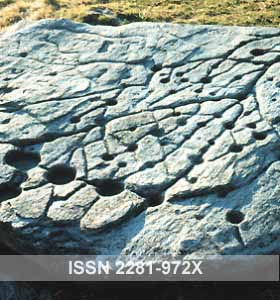

Ring Mountain Petroglyph Boulder

Perhaps the real success story at Ring Mountain focuses on the potential for rock art advocacy groups, like BARARA, to direct a communities' attention to the existence and inherent value of local rock art, and to mobilize the community to protect these cultural heritage sites.

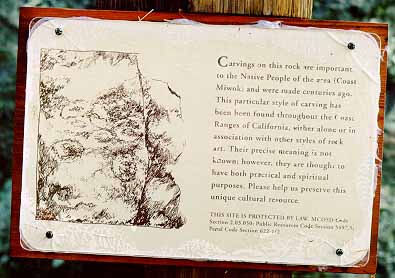

Showing new low rail barrier and interpretive sign At Ring Mountain

Specific conservation strategies grew out of BARARA’s commitment to the site and its self definition as a “catalyst” for community involvement. BARARA’s first action was to invite a broad representation of interested community groups to meet on behalf of devising protections for the site. This group included representatives from the local Native American community which laid cultural claims to the site, representatives of the owners of the site, and representatives from local museum, school, and archaeological societies which had a natural interest in the site.

A series of subsequent meetings led to the drafting of a Cultural Resource Management Plan. The draft plan was reviewed and commented on, not only by our new group of local stewards, but was also circulated widely to rock art specialists, Native American groups, and interested individuals. After hearing many voices, a consensus emerged from the review process. Any public interpretation of the petroglyphs would have to be sensitive not only to the archaeological record, but also to the sensibilities and views of the local Native Americans. Conservation strategies needed to conform to the edict, “Do no harm”, while at the same time effect interventions which had a chance to make a real impact on public behavior at the site.

The Petroglyphs

With a true community consensus in hand, BARARA was authorized by the larger planning group to advocate for the adoption of the plan by the owners of the site. This became a long drawn out affair where patience and persistence were the virtues that eventually helped win the day. Any running of bureaucratic gauntlets is bound to become somewhat byzantine, and the story at Ring Mountain was no different. Months turned to years while sympathetic bureaucrats refused to make the ultimate decisions that would allow the conservation activities to move forward. Opportunity finally presented itself when land ownership changed hands and the new owners, Marin Open Space District, embraced the communities’ involvement with enthusiasm.

Our group of advocates met with the park district in the Fall of 1996 to review our own proposals and to reach agreements on which of them would now go forward. At this meeting, one key proposal which was originally accepted by the Native American community was now rejected. There would be no “graffiti reintegration” at the site, that is, there would be no attempt to disguise existing scratched graffiti by in filling the small incisions with surface bonding acrylic paints.

We were informed that the living spirit of the stone would not be honored by physical interventions on the stone itself. What was done was done (in the form of the existing graffiti), but there should be no further marking on the surface for any reason. This proved to be a difficult response for the rock art conservationists among us to accept, as it is widely held that graffiti left in place will attract more of the same. A compromise position was reached in which all agreed to monitor the site closely and to revisit the issue at an annual meeting.

Of first importance was to create a base line document of existing conditions at the petroglyph site. We wanted to evaluate the impact of our proposed interventions and the measure was to be the rate of increase in graffiti at the main petroglyph boulder. To this end, Paul Freeman, BARARA Co-Chairperson, has led a small dedicated group of volunteers in creating a site recording document. The petroglyph panel was measured and photographed in meter squares. All petroglyphs and existing graffiti were then sketched on acetate overlays using the photo document and its grid lines as a referent. During the past year, at approximately 3 month intervals, the site has been revisited, and any new graffiti have been recorded by color coding on the acetate overlays.

Carvings on this rock are important to the Native People of the area (Coast Miwok) and were made centuries ago. This particular style of carving has been found throughout the Coast Ranges of California, either alone or in association with other styles of rock art. Their precise meaning is not known; however, they are thought to have both practical and spiritual purposes. Please help to preserve this unique cultural resource

At the beginning of January 1996, Marin Open Space installed a wooden, low rail barrier at the site, several feet away from, and parallel to the main petroglyph panel. Our intention was to suggest to the public an appropriate viewing distance and to create a psychological barrier to approaching closer. We wanted to avoid any fencing or caging that would detract from the serenity and sense of place, and we did not want to antagonize the public by imposing a structure which itself might become a target.

In the months that ensued, following the installation of the barrier, our group of stewards met again to advise the park district on appropriate wording for an interpretive sign at the site. Almost a year later, in November 1997, the interpretive sign was installed.

The Canyon Trails petroglyphs site in El Cerrito, shown here lit at Winter Solstice, is BARARA’s next conservation project

As promised, one year following our first meeting with Marin Open Space, BARARA hosted a luncheon (with expenses underwritten by a local business) to bring together the site stewards with Marin Open Space representatives for the first annual review of our conservation activities. BARARA shared its new site record and reported the occurrence of two new incidents of scratched graffiti on the rock. The park district reported that its own sign located to the back side of the site (one which requests that people do not climb on the rock in order to protect rare lichens) has been vandalized repeatedly. However, the park district itself is patient and has printed enough replacement signs to long outlast the vandals. All agreed that we should now wait to see what effects the new interpretive sign will have, that graffiti reintegration should remain on hold, and that local neighborhood groups should be encouraged to join the park’s volunteer program and be trained to become site monitors.

Of course, any one act of wonton vandalism can quickly undue all of our best efforts to protect the irreplaceable petroglyphs at Ring Mountain. We realize that our monitoring, our efforts to educate and involve the community, and our continuing reevaluation of our efforts is an ongoing commitment. Personally, my involvement is a small attempt to help repair this tiny corner of the world. And, as Ring Mountain enjoys its moment to breathe a sigh of relief, I find my attention wandering across the bay, to a small drainage, in a tiny city park in the community of El Cerrito, where a lone petroglyph boulder has attracted the graffiti tagging of a person, or persons, unknown.

Leave a Reply