TRACCE no. 12 – by Grant S. McCall

Why the Eland? An Analysis of the Role of Sexual Dimorphism in San Rock Art.

The eland is by far the most commonly depicted animal in Southern African art, and the most recognized by the modern viewer.

Yet, the reason for the dominance of the eland is still something of a mystery, and it has not yet been dealt with in a serious fashion. Not enough is known by modern researchers of San ethnography to ascribe properly mythological meaning to every animal (Garlake, 1995). However, even modern San ethnographies, including my own work among the Ju/’hoansi (formerly referred to as !Kung San), show that the San still have a strong connection with the eland in ritual and belief.

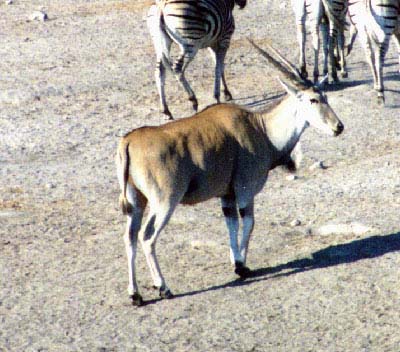

Male eland from Etosha Nat. Park in Namibia. The dewlap is of average size

My own research (which has been mainly just a passing gustatory interest) has shown several reasons for the popularity of eland among the Ju/’hoansi. The first is that the eland is very large, in fact the largest antelope in the world. Eland can exceed one ton in weight. Secondly, the eland has the most fat on it of any animal in the area. This can not be underestimated in a foraging society where calories are hard to come by. Lastly, and most relevant to my experience, eland are the most tasty of the large animals in the area. In fact, they taste very, very much like beef. I sense quantitative archaeologist-readers groaning at the inexactitude of this statement, perhaps favoring a caloric analysis, but I state again, eland is delicious. Eland have several other notable features. They are very athletic creatures, perhaps the most athletic of any antelope in the world. In fact, these massive animals are sometimes known to confuse predators by actually leaping over one another in flight. Their other notable feature is that they are renowned among the park rangers I discussed this with as being uncannily stupid. In fact, several of said rangers have described having to nudge eland with their vehicle to remove them from the road. Stupidity among prey animals is a highly desirable and venerated quality among hunter-gatherer cultures. This interesting combination of features has led to several attempts to domesticate the eland in modern times, some meeting with significant success.

A last feature which will be of particular concern to my argument is the sexual dimorphism of the eland. Males and females differ in a significant manner. Unlike many antelope, both sexes have horns. However, the male has a dewlap, which is a large fatty flap of flesh on the bottom of the neck. The female lacks this feature entirely. This particular dimorphism is entirely unique to the species.

Line of eland from Sevilla, in the Southwestern Cape. Note the male eland at the head, with characteristic male dewlad, depicted in dark red, while the females, with characteristic female neck lines follow, depicted in yellow-orange

Male eland from Sevilla showing characteristic male dewlap, with the body depicted in dark red

Female eland from Sevilla showing characteristic female neck line, with the body depicted in yellow-orange

To my mind, these features went a long way toward explaining the significance of the eland among the San. However, a particular depiction of some eland caught my attention on a recent visit to the Sevilla rock art trail in the South Western Cape region of South Africa.

The Sevilla trail is situated in the foothills of the Cedarberg mountains, in the valley of a reliable river. There are more than a dozen sites along the four kilometers of the trail. One site along the trail in particular had an unusually large number of paintings in it. One of the especially odd features of this particular site was a small cave above the main panel of painting. Standing on my companion’s shoulders, I managed to enter this cave, which I knew to contain paintings. There was a remarkable and well-known image on my right.

A yellow-orange colored eland, implying a female, from Solomonslaagte in the Southwestern Cape

There were some equally remarkable, but lesser discussed paintings of a herd of eland. What was truly remarkable was how well preserved the paintings were, completely sheltered in the cave. The white color which traditionally is faded in other paintings in the region is very well preserved on these eland. The white color is used to paint the legs, head, and neck of the eland. When the white fades away, it leaves behind the body of the animal, painted in another color. What is more remarkable about these eland is the color scheme in which they are painted. The eland leading the herd was depicted in a dark red color, and the following eland were depicted with yellow ocher.

When I examined the figures closer, to my astonishment I noticed that the leader had the characteristic dewlap of the male eland, and the following animals did not have the dewlap, and therefore must be considered female. In short, the male and female elands in the same herd were depicted in different color schemes. The artist was so concerned with sexual dimorphism of his subject matter that he went as far as to paint one in red, one in yellow. Indeed, with this in mind, I noticed several other depictions of eland in the area that followed the rule: males painted in red, females in yellow.

This is not an unheard-of idea. David Lewis-Williams and Thomas Dowson have suggested this notion of sexual dimorphism as a possible reason for the veneration of the eland (1989). They have suggested that San treated the eland in the fashion they did because of the unique differences between the sexes. In particular, he points out that the eland is unique because the male has more fat than the female. He assumes that the San are a naturally sexist society, and therefore would prefer the male, and since the male has more fat than the female in only this singular case, this makes for an obvious preference in terms of species.

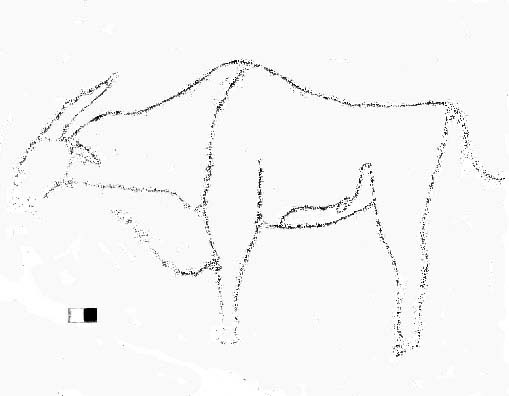

Engraving from the Transvaal showing an eland with both male and female neck and belly lines

Engraving from the Transvaal showing a male eland with an unrealistically large dewlap

While Lewis-Williams and Dowson perhaps take an extreme view of this situation, I agree that it is the sexual dimorphism that is important to the San. In this case in the Cedarberg, that importance takes the form of, in certain paintings, depicting the sexes in different colors. This notion also draws to mind an engraving from the Transvaal, pictured here, of an eland depicted with both male and female features. Lewis-Williams and Dowson intepret this engraving as indicating a San belief in the bisexuality of eland. However, to my mind, in the light of modern San ethnography, it indicates a heightened awareness of the sexuality of the eland, and of the differences between the sexes. Lewis-Williams also points to the following engraving (likewise from the Transvaal) of an eland with a massively exagerated dewlap, emphasizing the male sex of the animal.

The artist depicts the eland in a manner that says above all else that the subject is male, perhaps super-male. In contrast, in Zimbabwe, where the eland is not the most commonly depicted animal, the kudu takes its place. This is interesting because the kudu is another antelope with an extreme sexual dimorphism. Male kudu are distinguished by massive and majestic twisted horns. In addition, they are much larger than the females. They take on a distinctive gray color, while the females have reddish-brown color. The males also have thin white vertical stripes, which the females do not share. Here, too, it seems that differences between the sexes are a major part of the animal’s importance.

Also interesting is the difference in the ways in which the human sexes are portrayed. Males are depicted by and large as thin figures, with (obviously) penises. Females are portrayed with exaggeratedly fat flesh, and enlarged buttocks and breasts (Lewis-Williams, 1998). Here, too, is an emphasis on difference between the sexes.

What, then, explains this fascination with sexual difference among the artists? I believe the answer lies in the marked difference in gender roles in the San society. In terms of modern Ju/’hoansi ethnography, the socioeconomic roles of males and females are vastly different. In simplistic terms, one imagines in such a hunter-gatherer society men hunting and women gathering. However, the division of labor between the sexes among the Ju/’hoansi is extremely complicated. Indeed, there is a stark contrast in the economic functions of men and women. Men and women share very few tasks (Lee, 1979). It therefore seems plausible that the San would wish to emphasize sexual difference in their rock art.

No doubt there are much deeper reasons why eland, or the kudu, had such significance to the San. However, the sexual dimorphism of these species seems to be a major concern to the artist. This seems to fit into the broader socioeconomic framework of modern San hunter-gatherers. Perhaps for the San, the eland was a sort of analogy to their own society. So important to the order of the society — and its functioning as a unit in terms of economic success — was division of labor, and the broader difference in gender roles. It seems plausible that the obvious and peculiar sexual dimorphism in the eland was an apt analogy to the differences in gender role among their own society to the San.

Grant S. McCall

References

- Garlake, Peter. The Hunter’s Vision: The Prehistoric Art of Zimbabwe. University of Washington Press, Seattle: 1995.

- Lee, Richard B. The !Kung San: Men, Women, and Work in a Foraging Society. Cambridge UP: 1979.

- Lewis-Williams, David. Quanto? The issue of many meanings in southern African San rock art research. South African Archaeological Bulletin, 53:168, 1998. pp. 86-96.

- ——, and Thomas Dowson. Images of Power: Understanding Bushman Rock Art. Southern Book Publishers, Johannesburg: 1989.

back to index TRACCE no.

![]()

I find it strange that more carvings are not done with the Eland as the subject, I have been researching them because I acquired three carvings, Two book ends (10 in) and a (about 20 inch) carving of a mother and calf suckling, as yet no luck on origin or artist ( however it must be African), they all are made by one person. My point is “why are not more done with this subject?” other than Rock Art?. I must ask, is it some sort of taboo to represent them by African Artists? (All pieces have minor damage to Horns, as very ornately done)

Very confused in Florida

(All pieces are hand rubbed with I think Olive Oil, Due to the Book ends being a little more shiny than the Mother and calf, plus bookends are a bit more smoothed off on edges, that requires Olive oil to do that way on wood)

I relate all this info to show just how old and the quality of the pieces, decidedly not junk pieces, the book ends have been restored at some point on the flat pieces that hold the books, yes a shame, however the Eland carvings are very nice