Depictions of cats in rock all over the world art are frequently characterised by specific feline properties. The feline images at the petroglyph site of Foum Chenna in southern Morocco are much less idiosyncratic. Besides a general description of the rock art site of Foum Chenna, the current paper attempts at a re-evaluation of the image of the feline at Foum Chenna, simultaneously trying to fit the image into a chronology of Moroccan rock art.

by Maarten van Hoek

The Felines of Foum Chenna, Morocco

Maarten van Hoek – rockart@home.nl

*

Introduction

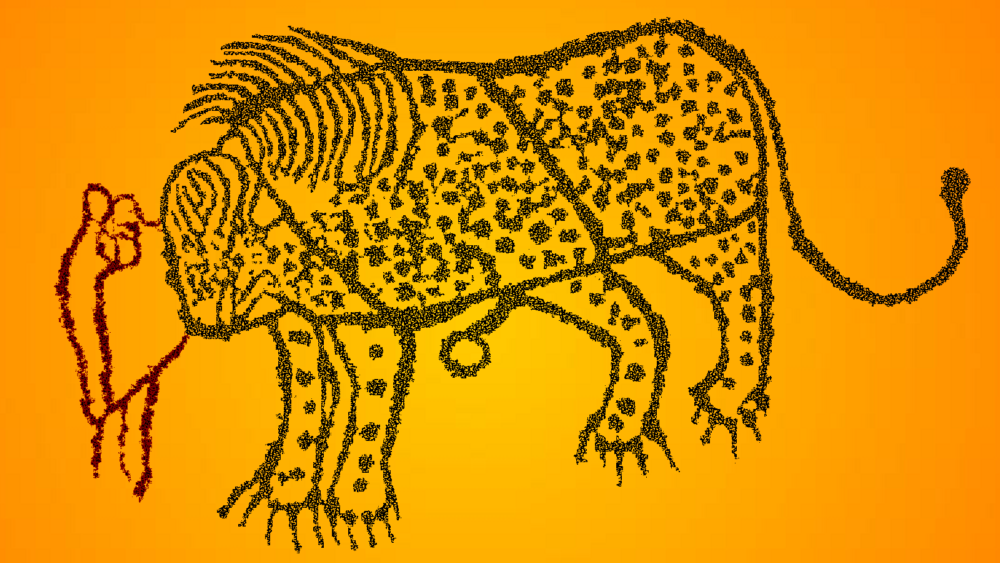

Depictions of cats in rock all over the world art are frequently characterised by specific feline properties. Often the teeth or the fangs and especially the typical (outlined and often dotted) body, the claws, the tail and the ears provide clear indications that a big cat has been d epicted. Fine Saharan examples are a large lion petroglyph from Niger (Coulson and Campbell 2001: Fig. 258) and the impressive petroglyph of a lion at Ouan Houas in the Mertoutek Region of the Haggar (Algeria), both showing fierce claws. Importantly, according to Ernesto Oeschger (2004: 19) this latter lion petroglyph was turned into a hybrid animal by adding a second head at a later stage (see Figure 50).

The feline images at the petroglyph site of Foum Chenna in southern Morocco are much less idiosyncratic. Actually, the much stylised and unembellished match-stick representations of the feline at this site are mainly identified by a fully pecked, small round head and the position of the long tail. Yet this does not mean that those rather featureless feline petroglyphs are not interesting. Closer inspection of a number of specific feline petroglyphs may offer useful information. Besides a general description of the rock art site of Foum Chenna, the current paper attempts at a re-evaluation of the image of the feline at Foum Chenna, simultaneously trying to fit the image into a chronology of Moroccan rock art.

In order to more fully appreciate the site of Foum Chenna, the complementary maps, photographs and drawings of this paper, I have made a video about Foum Chenna in which the same illustrations appear (except for Figure 50). However, the video also shows several other photos of Foum Chenna petroglyphs, but the numbering of the illustrations in the paper and in the video is the same. The illustrations in this paper have one standard size. Click any illustration to enlarge (all illustrations will open in a new window). All photos in the paper and in the video have been digitally enhanced to show up better. To view some illustrations in more detail I recommend using the video.

*

First Part: The Location of Foum Chenna

Foum Chenna is a major petroglyph site in the Anti Atlas Mountains of southern Morocco (Figure 1). It is located on the western bank of the well known river Drâa (région: Souss-Massa-Drâa; province: Zagora; commune: Tinzouline); a large part of its drainage shown in Figure 2. The site was first reported as Oumchena in 1942 by Marcel Reine (Pichler 2000: 176), but in this paper I ignore the many alternative names for this site. It has been registered as site 15/0044 in the Catalogue des Gravures Rupestres du Sud Marocain (Simoneau 1977) and described as Zone 6 – Site AA1 by Susan Searight (2001: 120-130). Nowadays the site is clearly signposted in the village of Tinzouline on the main Ouazarzate-Zagora road (N9) and can be reached from the sign by following a dirt track (Figure 3) to the WSW for about 6.7 km (as the crow flies).

Figure 1. Map showing the location of Foum Chenna in southern Morocco. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on based on Google Earth Relief Maps. The green squares indicate the major High Atlas rock art sites.

Figure 2. Map showing the location of Foum Chenna in the Anti Atlas of southern Morocco. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on based on Google Earth Relief Maps. The yellow squares indicate the rock art sites of Figure 6. The green squares indicate the approximated locations of other rock art sites in the area.

Figure 3. The dirt-track leading to the rock art site of Foum Chenna (location indicated by the yellow arrow); looking WSW. Photograph Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Nowadays it is a myth to think that not revealing the location of well-known rock art sites will prevent vandalism. As at least two web sites reveal the exact location of rock art sites in the Upper Drâa Valley (Le Maroc avant l’histoire and Gravures NO Zagora), two of which are also indicated in the accurate map of Fig. 1 by Marcel Reine (1969; PDF available on-line), I have no problem presenting my location maps in the current paper (and video), but I sincerely hope that every visitor will respect and protect the rock art and the environment at Foum Chenna (and elsewhere!). Therefore, please report to the warden before visiting the site.

Foum Chenna is one of at least four rock art sites that are situated in a low, ESE-NNW running mountain ridge (Figures 4 and 5). This approximately 45 km long ridge is probably the western extension of Jebel Azlag and this ridge has its highest summit at 1550 m O.D. (1575 m according to the O.S. Map NH 29-8 [1956]). The maps of Figures 6 and 7 show the following four rock art sites (from ESE to NNW): 1): Chaba el Beida – also known as Rich de M’Bidia (Pichler 2000: 176), also listed as Zone 8 – Site S1 by Susan Searight (2001: 300) – at 880 m; 2): Assif Ouiggane – also known as Assif Wiggane – at 1185 m; 3): Foum Chenna at 1000 m and 4): Djorf el Rhil at 1095 m. All four sites concern petroglyph sites, although at least one panel with rock paintings is said to have been recorded in the pass of Assif Ouiggane (see a photograph by Ibrahim Lamnay 2014).

Figure 4. Part of the low mountain ridge in which at least four petroglyphs sites have been recorded, looking SW. Photograph Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure 5. Part of the low mountain ridge in which at least four petroglyphs sites have been recorded, looking south. Photograph Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure 6. Map showing the location of Foum Chenna in the Drâa Valley of southern Morocco. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on based on Google Earth Relief Maps. The green square indicates the location of the Foum Chenna rock art complex; the yellow squares indicate other rock art sites in the Drâa Valley.

Figure 7. Map showing the altitudes of the sites in the Drâa Valley mentioned in the text. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on based on Google Earth. The yellow squares indicate rock art sites. The green squares indicate the locations of some settlements and fortifications in the area.

As I only surveyed Foum Chenna, the altitudes of the other three rock art sites have been approximated by me, as have their locations on the maps (all distances and altitudes in this paper are based on Google Earth). Observations concerning all other rock art sites mentioned in this paper are based on previously published works and on photographs by other people, many of which have been uploaded onto the internet.

The Four Foum Chenna Petroglyph Sites

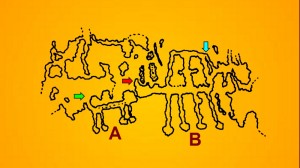

There are actually four petroglyph sites (Figure 8) in the small valley in which Oued Chenna is located (Oued means river or stream). Site Foum Chenna 1 (the main site) is found at the NW bank of the dry river valley (Figure 9). Near the entrance and NE of the main part are some isolated petroglyph boulders on the less steep hill slope (Figure 10). However, the biggest part of Foum Chenna 1 is a steeply sloping rock wall comprising a much fragmented outcrop of hard sandstone – probably quartzite (Figure 11) – and many mainly angular blocks of stone at the foot of the cliff. Most probably most of these boulders once tumbled down from the cliff. The area with petroglyphs – starting at an altitude of about 1000 m O.D and extending roughly 20 m in height from the present-day (artificial) ground level – measures approximately 90 m in length from NE to SW.

Figure 8. Map showing the locations of the four rock art sites at Foum Chenna. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on based on Google Earth. The yellow square indicates the approximated location of Foum Chenna 4.

Figure 9. Map showing the locations of the rock art site of Foum Chenna 1. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on based on Google Earth.

Figure 10. The NE part of the rock art site at Foum Chenna 1, looking north across the gravel plain, the Drâa Valley in the distance and the mountain ridge of Jebel Bou Zeroual beyond. Photograph Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure 11. The SW part of the rock wall at Foum Chenna 1, looking north. Photograph Copyright by Maarten van Hoek. The numbers 5 and 7 refer to Panels 5 and 7 discussed in this paper.

Especially the main site has suffered a lot of damage, most of which has been caused by natural forces. Prof. Werner Pichler, well known for his research into the ancient Libyco-Berber inscriptions of northern Africa and the Canary Islands, already noticed progressive erosion at Foum Chenna. He remarked that ‘During the last fifty years a great number of boulders, including some with engravings, fell down.’(Pichler 2000: 176). Moreover, Susan Searight remarks that – probably in 1994-1995 – a heavy downpour at Foum Chenna damaged many panels and overturned and (partially) buried several detached petroglyph boulders (Searight 2001: 121). Fortunately there is only very little evidence of recent anthropic damage such as vandalism (see however Figure 19), also because the site is supervised by a warden living near the entrance.

Nowadays an ugly but indispensable concrete platform of about 40 by 15 m in front of Site 1 – with two open shelters offering a little shade – has been constructed in order to protect the rock art against future flooding and further (natural and anthropic) damage. Several (concrete) walls protect much of the northern side of the valley (also Sites 2 and 3 are protected). After 2011 some of the once buried petroglyph boulders proved to have been relocated (for instance a fine petroglyph boulder in front of panel 34), thus better showing the still good quality images. Many other boulders are still (partially) buried however.

Site Foum Chenna 2 is a small outcrop/boulder site with only a few petroglyph panels (Figure 12). It is also located at 1000 m O.D., approximately 286 m south of Site 1, while Site 3, also small, is an outcrop/boulder site (at 1006 m O.D.) which is found 375 m SSW of Site 1. Site 3 has a slightly larger number of panels with images (Figure 13). I did not visit Site 4 (Figure 14), which is said to be a minor site located at the opposite (western) side of the valley (Reine 1969: 39). I estimate Site 4 to have an altitude of 1000 m O.D. as well, while it may be located about 340 m SE of Site 1. The valley floor at its widest point is 385 m (NW-SE), while the actual mouth of the now dry river valley measures 210 m (NW-SE). The altitude of the valley floor at that point is about 980 m.

Figure 12. Part of the rock art site of Foum Chenna 2, looking NNW. Photograph Copyright by Maarten van Hoek. The yellow arrows indicate two outlined petroglyphs.

Figure 13. Part of the rock art site of Foum Chenna 3, looking NW. Photograph Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure 14. Looking SW from Foum Chenna 1 across Oued Chenna towards the estimated location of Foum Chenna 4. Photograph Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Relevant Local Archaeology

There are numerous ancient structures in this mountain ridge, many clearly visible with Google Earth (see for instance Figure 8). Most of these chiefly small structures probably are ancient cattle pens that are mainly found in the valleys. Their occurrence proves that the area – now a dry and deserted desert – has seen wetter and thus better times. According to Marcel Reine (1969: 37) the valleys that traverse the mountain ridge were once used to reach the Grara area, much further SW of the ridge (see Figures 6 and 7), which is rich in metal ores. This probably is also the main factor explaining the above average occurrence of rock art in this now inconspicuous valley.

In this context it is significant to note that at least two of the valleys in the mountain ridge that have rock art also have complexes of ruins that most likely are ancient villages and, more importantly, fortifications. In Assif Ouiggane is an oppidum (fortification) on a small natural platform (at 1185 m) that itself has a large number of petroglyph rocks (Searight 2001: 95, 298). Moreover, in its immediate neighbourhood at least three other petroglyph sites (and possibly one site with a rock painting) have been reported by Ibrahim Lamnay in 2014; all four sites pinpointed north of the oppidum by him. Two of those sites may the same as the rock art sites previously recorded by André Simoneau (1974: 29 – 30) in the Assif. WSW of the oppidum and at a lower altitude (1105 m) is a complex of ruins. This complex possibly is an ancient village that is located very near the ancient pass through the ridge (indicated with a dotted line in Figure 7).

A similar situation is found at the Foum Chenna pass. On top of the hill of which Site 1 forms the SW facing cliff is a large complex of a cluster of buildings (at 1070 m O.D) and at least five parallel, curved walls that clearly have been arranged to form lines of defence (see Figure 9). Obviously the fort is in a very strategic position, controlling the northern entrance of the pass and the flat, gravely expanses further north and east (Reine 1969: 39). About 3 km to the SW in the same pass is another fortification (at 1345 m) as well as a possible village very near the valley floor (at 1069 m); both at the west side of the pass. There are at least two more possible fortifications in the immediate neighbourhood. One is found at 1240 m at the east side of the valley; the other is at 1160 m at the west side (both not shown in Figure 7). Especially the fortification at 1069 m has a commanding position overlooking and controlling the southern entrance to Foum Chenna. The above average representation of rock art, the fortifications, the ancient villages and the cattle pens in the Foum Chenna valley clearly emphasise the importance of this ancient corridor.

*

Second Part: Rock Art of Foum Chenna

It is estimated that Foum Chenna has more than 3000 individual petroglyphs (Reine 1969). It must be emphasised however that Susan Searight (2001) explicitly remarks that the disturbed situation at Foum Chenna inhibits the exact recording of the alleged 3000+ images at Foum Chenna. This disturbed situation still exists nowadays, although protective measures have been taken in order to prevent further disturbance by occasional floods. It seems however that her 2001 survey only deals with Site 1. Her Table 22 includes 425 units on 216 panels without stating whether all four sites have been included. Yet Searight mentions the existence of more petroglyphs ‘up valley’ (probably referring to Sites 2 and 3 and possibly Site 4 as well). It is not my intention to fully describe all the rock art panels that I have surveyed at Sites 1, 2 and 3. Instead, in the current paper I focus in particular on representations of the feline at Foum Chenna.

The petroglyphs at Foum Chenna were predominantly made by pecking out match-stick figures. A few (pre?)scratched figures – again, mainly at Site 1 – have also been recorded. An example is marked with a light-blue arrow in Figure 15 and enlarged in Figure 16: petroglyph C. More deeply incised markings are very rare. There are however many clearly unfinished petroglyphs. Most images consist of single-line compositions and fully pecked elements; outlined figures occur only very sporadically. I only know of at least two definitely outlined zoomorphs – possibly camelids – on two panels of the outcrop at Site 2 (marked with yellow arrows in Figure 12), and two possibly outlined anthropomorphic figures at Site 1 that both look more recent.

Figure 15. Part of the rock wall at Foum Chenna 1, looking NNW. Photograph Copyright by Maarten van Hoek. The arrows indicate several features mentioned in the text. Light blue arrow: Figures 16, 17 and 18; green arrow: Figure 26.

Figure 16. Petroglyphs on a panel at Foum Chenna 1, southern Morocco. Photograph Copyright by Christophe Vigerie, 2011: photo 60, reproduced here with his kind permission (2014: pers. comm.). The information in the photograph has been added by the author.

A photograph of panel Chenna 1 – 31, published on the internet and probably taken by Werner Pichler (2007), shows the almost un-patinated petroglyphs of an anthropomorph and a camelid, both with an outlined body. These instances may be much younger than the standard repertoire at Foum Chenna as seems to be confirmed by the following text (Skounti et al. 2003: 93; cited by Werner Pichler 2007): ‘L’anthropomorphe et le dromadaire à la bosse exagérée à gauche sont très récents, peut-être même contemporains: non seulement leur patine est claire, mais la technique utilisée pour les dessiner est totalement différente de celles des figures environnantes’.

This does not mean that outlined figures are always younger. Possibly four or five petroglyphs of ostriches, larger than the average Libyco-Berber petroglyphs, prove to have an outlined body. They are found on a large, almost vertical wall at Foum Chenna 1, roughly measuring 4 m in width and 2 m in height (approximate positions marked with four blue arrows in Figure 15; the ostrich petroglyphs are too much patinated to show in this photograph). The style of those outlined ostriches is similar to those found at Adrar Temgart Issardane (Simoneau 1976: Fig. 11a), a petroglyph site NW of the town of Akka and 235 km SW of Foum Chenna. Close inspection of the petroglyph panels at Foum Chenna may reveal more examples of such outlined petroglyphs that probably are older than the standard petroglyph art at Foum Chenna.

Most likely the great majority of the petroglyphs at Foum Chenna are of Libyco-Berber origin (as are the other three petroglyph sites in this low ridge). Werner Pichler (2000) argues that, basing upon the occurrence of camels and horses, a very plausible hypothesis is to date the whole ensemble of the Foum Chenna engravings back to the second half of the first millennium B.C., while – relevant in this work – Marcel Reine (1969: 40) seems to place the feline petroglyphs to the Third Stage (The Horse Period) and the Fourth Stage (the Camel Period) of Foum Chenna. In this paper I would like to suggest a slightly different chronology for the feline at Foum Chenna.

Indeed, differences in patination indicate the use of the site over a rather long period of time, while some images look relatively modern. Superimpositions are rare but do occur especially at more crowded panels. I already mentioned the large petroglyph wall that has possibly four or five outlined petroglyphs of very ancient looking outlined ostriches (indicated with four blue arrows in Figure 15). Several of those ostriches are clearly superimposed by later petroglyphs. One of those petroglyphs (indicated with a light blue arrow in Figures 15 and 17) shows an outlined ostrich that is partly pecked and partially abraded/polished. It has a very long, single line neck; the (very small?) head seems to be missing or was lost in a crack. This ostrich (red in Figure 18) is clearly superimposed by later images (black in Figure 18).

To the left of the ostrich is a circular pattern of widely distributed markings (A in Figure 16; yellow arrow in Figure 17) that may well represent the draft sketch of an unfinished ostrich petroglyph. The circle is superimposed by a brighter petroglyph of a mounted zoomorph (B in Figure 16); a much stylised feline perhaps? Between the ‘ostrich’ and zoomorph B is a zoomorph that is partially (pre?)scratched and partially pecked; even the faint indications of a rider with its shield are visible (C in Figure 16; the shield indicated with a green arrow in Figure 17).

Below the ostrich petroglyph – on a rather rough patch of the rock – is a previously unrecorded (?) line of Libyco-Berber inscriptions (red arrow in Figures 15 and 17; marked in white in Figure 18). Prof. Lionel Galand has been so kind to examine the line of inscriptions in Figure 17 for me and he confirmed that ‘two or three of the signs ….. look like genuine ‘Berber’ characters; the other ones are not clear, but we might admit that this is an ancient inscription’ (2014: pers. com.).

Figure 17. Petroglyphs on a panel at Foum Chenna 1, southern Morocco. Photograph Copyright by Christophe Vigerie, 2011: photo 59, reproduced here with his kind permission (2014: pers. comm.). The information in the photo has been added by the author.

Figure 18. Petroglyphs on a panel at Foum Chenna 1, southern Morocco. Drawings Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on the photograph (Figure 17) by Christophe Vigerie, 2011: photo 59. The colour-information in the drawing has been added by the author.

One boulder at the NE end of Site 1 shows a number of completely patinated, fully pecked petroglyphs superimposed by recent looking, un-patinated markings (Figure 19). Marcel Reine suggests that the deeply patinated petroglyphs on this boulder belong to the First Phase of rock art production at Foum Chenna (1969: 39; see his Fig. 15 [his Figs 3 and 15 – or their captions -should be switched]). The drawing by Marcel Reine (1969: Fig. 15 ) does not show the un-patinated markings (Figure 20) and therefore they most likely represent recent instances of unwanted vandalism made after his visit to the site.

Figure 19. Vandalised petroglyph boulder near the NE end of Foum Chenna 1. Photograph Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure 20. Drawing of the ancient petroglyphs on the vandalised boulder of Figure 19. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Marcel Reine (1969: Fig. 15 – 3).

Several petroglyphs (mainly at Site 1) look like being obliterated on purpose by later random pecking (centre of Figure 21). It is unknown to me at what stage this has been done, but those instances may also be regarded as a kind of palimpsest. The act of (ritually?) obliterating earlier images may have had a specific symbolic meaning and reminded me of possibly similar situations in the Andes of South America (Van Hoek 2007).

Figure 21. Petroglyph panels at Foum Chenna 1. Photograph Copyright by Maarten van Hoek. The numbers 4 and 7 refer to Panels 4 and 7 that are described in this paper. The alleged obliterated petroglyph is visible to the left of the 7.

The Imagery at Foum Chenna

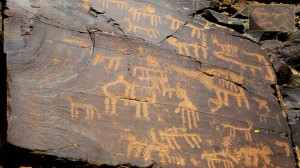

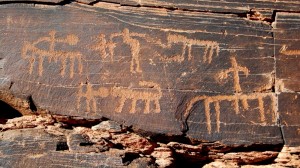

The recognisable images at Foum Chenna mainly include horsemen, felines, birds (ostriches and bustards), sheep, horses, dogs, camelids (dromedaries), anthropomorphs and lines of Libyco-Berber inscriptions. Also numerous unidentified zoomorphs and further ‘enigmatic’ or amorphous markings – including ‘random’ pecking – have been recorded.

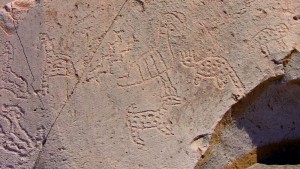

The petroglyphs at Foum Chenna are often arranged in scenes depicting confrontations, like fights or hunts. Fights between different groups of warriors, or the hunting of felines, sheep and ostrich, or simply the close association of animals and humans in a small panel are characteristic of the standard Libyco-Berber style (Searight 2001: 123).

Most biomorphic images at Foum Chenna are represented in the ‘standard’ position, which means that they have been drawn with vertically drawn legs pointing downwards (more general info about this subject). Thus, the human body and legs have been drawn in a vertical position and the body of the zoomorphs (felines, horses and camelids) in a horizontal position; their legs in a vertical position. Yet, some zoomorphic images appear in a vertical position. One vertical rock art panel at Assif Ouiggane features an upside-down petroglyph of a (dead?) feline that – seemingly – is attacked/devoured (?) by another feline (Figure 22). These petroglyphs are found on a fixed outcrop wall and thus the rock and image could not have been rotated.

Figure 22. Feline petroglyphs at Assif Ouiggane, southern Morocco (the other petroglyphs on this panel have been omitted). Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek; based on a photograph by Ibrahim Lamnay 2014.

There are some unexpected images at Foum Chenna. For instance, one petroglyph at Site 1 shows a horseman apparently sitting backwards on the horse’s back (observe his feet), while holding a curved object (Figure 23); a bow perhaps? Two petroglyphs, also at Site 1, may represent daggers (approximately 17 cm in length); their triangular ‘blades’ pointing downwards (their locations are indicated with two yellow arrows in Figure 15).

Although Susan Searight claims that human hands on their own have only been noted in the High Atlas (2001: 69), one large petroglyph on Panel 5 at Site 1 may well be interpreted as a downward pointing human hand (Figure 24; see also Figure 38). The image may be regarded to depict a right hand or, when it is the back of the hand that faces the observer, a left hand. The age of this petroglyph is unknown, but it may be related to the well-known symbol of ‘Fatima’s Hand’; one of the characteristic elements from the Arabic iconography. However, hand symbols in Saharan rock art may of course be much older (Oeschger 2004: 6).

Figure 23. Petroglyph panel at Foum Chenna 1. Photograph Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure 24. Panel 5 at Foum Chenna 1; the yellow arrow points to a possible dog petroglyph. Photograph Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

As a rule sexual organs are not shown, except for one lance-carrying horseman petroglyph and a few other horse petroglyphs, all at Site 1, in which the stallions seem to show male genitals (see some examples in the video: fourth part). However, male gender is probably frequently indicated by the objects carried by the anthropomorphic figures and by the rider-animal configurations.

Feline Petroglyphs at Foum Chenna – Introduction

Because Susan Searight rightly acknowledges the general difficulty to identify animal species of the very schematic style of the Foum Chenna petroglyphs, I refer in this paper to the possible representations of leopards, panthers and/or lions as ‘felines’.

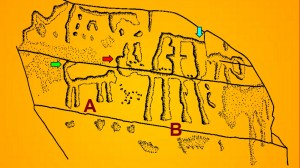

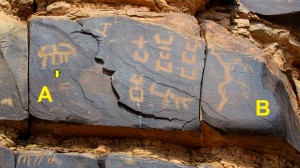

Although Susan Searight (2001: Table 22) listed 27 felines on 20 panels at Foum Chenna, I am sure that there are more examples, but she rightly refers to numbers as minima. Regarding the definition of a ‘panel’ it is a problem that it is not clear how Searight defines a panel. For instance, her panel 33 (2001: Fig. 30c), a vertical rock face, labelled Panel 4AB in this paper and situated a few metres NE (right) of my Panel 7 (Panel 4 not shown in Figure 11), said to comprise 1 horseman, 1 Barbary sheep, 3 lines of Libyco-Berber letters, 1 serpentiform (2001: 127), may as well be regarded to represent two panels (A and B in Figure 25) as the serpentiform – showing a triangular head – is located on Panel 4B, to the right of a well-defined crack.

Figure 25. Petroglyph panels at Foum Chenna 1. Photograph Copyright by Maarten van Hoek. The numbers (except Panel 4A and B) refer to the numbering used by Susan Searight (2001).

Another problem is that her descriptions of the images on the panels do not seem to match with the factual content of the panels. This applies to her panel 33, where one of the zoomorphic petroglyphs (either interpreted by Searight as a horseman or a Barbary sheep) may actually represent a feline. This issue will be explained further on.

Also the description of her panel 34 is confusing as it is not clear which sections actually are parts of panel 34 (Figure 25). According to Searight, 3 horsemen, 1 man on foot, 2 leopards/lions, 4 not identified animals, 2 bustards, 1 line of Libyco-Berber letters, 1 oval, 1 enigmatic appear on panel 34 (2001: 127; Fig. 30c). Searight moreover remarks that panel 34 features ‘three horsemen and a man on foot that are closely associated with two felines and two bustards’ (2001: 129). However, after close inspection of my photographs of this part of the rock cliff I could not distinguish this scene of ‘closely associated images’, because the two felines and also the two bustards could not be traced. In fact, there may well be more feline petroglyphs on this panel.

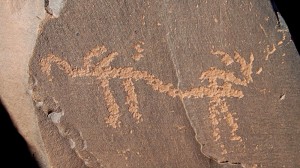

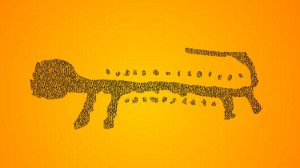

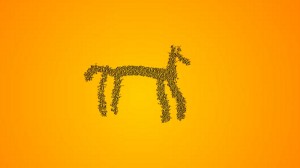

In general depictions of felines at Foum Chenna are characterised by a rather long, horizontally orientated body consisting of one single groove that ends in a small, fully pecked round head that is without any detail. In general there is no neck or just a very short neck. The (typical triangular or semicircular feline) ears are invariably absent (while ears often show in horse, dog and camelid petroglyphs). The other end of the body continues as a long tail that is almost invariably hovering over the back of the animal, either curved or straight. The upward-pointing tail is one of the main characteristics of the feline and distinguishes the Foum Chenna feline from horses, sheep and camelids that have a downward-pointing tail. Petroglyphs of dogs also may display an upward pointing tail, but dogs usually are distinguished by their narrow, often pointed head with distinctive ears (see video -fourth part- and the yellow arrow and inset in the right-hand top corner in Figure 24). The four legs of the feline are either closely grouped in two pairs (for example feline A in Figure 29) or the legs are evenly distributed below the linear body (feline B in Figure 29). The paws are often – but not always – indicated by slightly larger dots (although petroglyphs of some other zoomorphic species show those features too). At least in one case the paws show ‘toes’ (see Figure 40) and in another case even claws (see Figure 38).

Although some feline petroglyphs apparently occur in ‘isolation’ (i.e. not directly associated with other images on the same panel), most felines seem to be hunted or chased by humans or they are pursuing other zoomorphs. In at least two scenes an armed anthropomorph on foot seems to be confronting a feline. One panel (Figure 26A; location of this panel marked by the green arrow in Figure 15) shows one of those scenes in which an anthropomorph on foot is confronting a feline, its shield almost touching the feline’s head (A in Figure 26B). Above this miniature scene are a cross-mark – a Libyco-Berber inscription? – and a strange, flexed anthropomorphic (?) figure. Also this latter element (marked with ‘?’ in Figure 26B) might represent a Libyco-Berber inscription that possibly has been animated (anthropomorphised) and linked to the adjoining petroglyphs. However, Prof. Lionel Galand – after examining Figure 26A – commented that there was no question of real writing in this case (2014: pers. com.).

Figure 26A. Feline petroglyph and possible Libyco-Berber inscriptions on a panel at Foum Chenna 1, southern Morocco. Photograph Copyright by Christophe Vigerie, 2011: photo 58, reproduced here with his kind permission (2014: pers. comm.).

Figure 26B. Feline petroglyph and possible Libyco-Berber inscriptions on a panel at Foum Chenna 1, southern Morocco. Photograph Copyright by Christophe Vigerie, 2011: photo 58, reproduced here with his kind permission (2014: pers. comm.). The information in the photograph has been added by the author and the interpretation is his responsibility.

*

Third Part: The Felines of Foum Chenna

Important in the scope of this paper is that several feline petroglyphs at Foum Chenna are physically linked with elements directly attached to their body, mainly to their backs. Such elements range from amorphous and therefore ‘enigmatic’ components to a petroglyph that is clearly identifiable as a bird. Because it is not my intention to describe all the feline petroglyphs at Foum Chenna, only eight panels with distinctive feline petroglyphs from Foum Chenna 1 will be discussed here in more detail. The order in which these panels (Panels 1 to 8) are described is completely arbitrary.

Panel 1

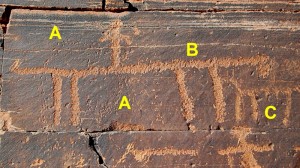

The NE part of Panel 1, located at the bottom of the cliff, clearly shows four felines that all are looking into the same direction, probably NE (Figure 27). Felines A, B and C are clearly hacked, while feline D seems to be pecked. Feline D seems to be ‘enclosed’ by two anthropomorphic figures, each armed with a round object; most likely a shield (almost as big as the human figure). The head of the feline is larger than expected, especially when compared with the three other felines on Panel 1. Moreover, it is almost similar in size to the shield of the person standing in front of the feline. The head of the feline may have been re-pecked (and possibly enlarged) at a later stage. Feline D also has an enigmatic object on its back. This circular object may be a shield petroglyph, although it is a quite illogical place for a shield. For that reason it may be something else (the hump of a camelid?) or even somebody else as the element might represent a rider. It namely seems that there are more instances at Foum Chenna where anthropomorphs are ‘riding’ animals that normally cannot be ridden.

Figure 27. Feline petroglyphs on Panel 1 at Foum Chenna 1, southern Morocco. Photograph Copyright by Christophe Vigerie, 2011: photo 9, reproduced here with his kind permission (2014: pers. comm.). The information in the photograph has been added by the author.

Panel 2

Panel 2 appears on a fallen block of stone (Figure 28). The original position is shown in Fig. 5 (circle 1) of the paper by Marcel Reine (1969). The feline on Panel 2 has no neck and a straight tail hovering over the back. However, there are two pecked areas, one apparently emerging from the back and another from the round head. The pecked area from the back seems to continue and is superimposed by the tail of the feline. The meaning of those pecked areas is unknown and it is also uncertain whether they actually are associated with the feline. The groove from the back may actually be the lower part of a zoomorphic figure once existing above the feline (see Reine 1969: Fig. 5).

Figure 28. Feline petroglyph on Panel 2 at Foum Chenna 1, southern Morocco. Photograph Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Panel 3

This panel is still in situ (2013) and features two zoomorphic petroglyphs (A and B in Figure 29) that I interpret as two confronting felines. As one feline is distinctly smaller, the scene may be interpreted as a harmonious adult-and-cub configuration, rather than a conflict scene.

Figure 29. Feline petroglyphs on Panel 3 at Foum Chenna 1, southern Morocco. Photograph Copyright by Maarten van Hoek; A and B refer to the description in the text.

The web page describing Panel 3 (listed as Chenna 1 – 41 in the LBI-Project web site of Werner Pichler [2007]) includes an older drawing of this panel (Earlier Documentations: Fig. 1) that shows a very short tail of the smaller feline (green arrow in Figure 30) and different configurations of the head and tail of the larger feline (respectively the red and blue arrows in Figure 30). The final drawing by Werner Pichler (2007: Fig. 1) shows a somewhat longer tail of the smaller feline (green arrow in Figure 31) and another configuration of the head and tail of the larger feline (respectively the red and blue arrows in Figure 31).

Figure 30. Feline petroglyphs on Panel 3 at Foum Chenna 1, southern Morocco. Drawing: Copyright by Werner Pichler/Institutum Canarium (2007: Earlier Documentations; Fig. 1). A and B and the arrows refer to the description in the text.

Figure 31. Feline petroglyphs on Panel 3 at Foum Chenna 1, southern Morocco. Drawing Copyright by Werner Pichler/Institutum Canarium (2007: Fig. 1). A and B and the arrows refer to the descriptions in the text.

It now seems that the smaller feline (13 cm in length) actually has a longer tail. Moreover, the layout of the larger feline (21 cm in length) has possibly been blurred by earlier images and/or later additions, which create the confusing impression of a large camelid figure. I have tried to reconstruct the image of the two felines (Figure 32), but it is possible that especially the tail of feline B is longer and/or differently curved. Also in this case it is possible that the central part of the configuration on the back of the larger feline (Figure 33) represents an anthropomorph. It may perhaps represent a rider, as several petroglyphs of horsemen and camelids at Foum Chenna feature similarly stylised riders.

Figure 32. Feline petroglyphs on Panel 3 at Foum Chenna 1, southern Morocco. Drawings Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure 33. Feline petroglyphs on Panel 3 at Foum Chenna 1, southern Morocco. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Panel 4

Previously not recognised as a feline is a zoomorphic petroglyph on Panel 4 (yellow arrow in Figure 34). Susan Searight interpreted the zoomorph possibly as either a Barbary sheep or – more likely – as a horseman (2001: 127, panel 33: Fig. 30c), the latter interpretation allegedly more appropriate because of the much stylised ‘anthropomorph’ that seems to be sitting on the back of the animal. Also the drawing by Werner Pichler (2007: Fig. 2) of Panel 4 (listed as Chenna 1 – 15 in his LBI-Project) seems to confirm the interpretation of a horseman (Figure 35).

Figure 34. Petroglyphs on Panel 4 at Foum Chenna 1. Photograph Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure 35. Petroglyphs on Panel 4 at Foum Chenna 1. Drawing Copyright by Werner Pichler/Institutum Canarium (2007: Fig. 2).

However, in my opinion the zoomorph – measuring approximately 15 cm in length – appears to be an altered petroglyph of a feline. There are two indications that support this assertion. Firstly, the patination of the original feline is slightly darker than the added/altered parts, and secondly, the – in my opinion – added parts are more crudely and unevenly executed (Figure 36). When using different colours for the original and the added parts the image of a feline undeniably emerges (Figure 37: several surrounding markings have been omitted). Again, the reconstruction of the feline’s tail is uncertain. The whole combination seems to have been an attempt to change the original feline petroglyph into an image of a horseman. This might be an indication that feline representations at Foum Chenna are generally older.

Figure 36. Petroglyph on Panel 4 at Foum Chenna 1. Photo Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure 37. Petroglyph on Panel 4 at Foum Chenna 1. Drawings Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Panel 5

Near the SW end of the main cliff at Foum Chenna 1 is an interesting panel (location indicated in Figure 11). It features the large left hand petroglyph and many other images, including some felines (see Figure 24). One rather large feline petroglyph shows claws; a rather unique feature at Foum Chenna (Figure 38). Interestingly, the feline petroglyph has been superimposed by or is superimposing a second petroglyph, or the ensemble was intentionally made by the same hand at the same time. A careful (but probably subjective) reconstruction (Figure 39) reveals the possibility that the second petroglyph represents a bird (an ostrich perhaps?). It is unknown if this configuration was intended or that it represents one of the scarce instances of unplanned superimposition. It is also unknown to me which petroglyph is older.

Figure 38. Petroglyphs on Panel 5 at Foum Chenna 1. Photo Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure 39. Petroglyphs on Panel 5 at Foum Chenna 1. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Panel 6

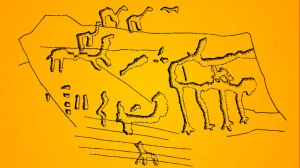

A petroglyph panel that I have seen – but did not photograph – is shown in the paper by Marcel Reine (1969: Fig. 6; Circle 4). Panel 6 is also listed as Chenna 1 – 38 in the LBI-Project of Werner Pichler where a good photograph (2007: Fig. 1; see Figure 40) and a drawing (2007: Fig. 2; see Figure 41) have been included. The feline – measuring 20 cm in length – shows four evenly distributed legs, all ending in three-toed paws. The curved tail ends at (or touches) a curved groove that is clearly no part of the feline. Between that groove and the back of the feline is an area with rather crude markings. When graphically separating the feline from the other features a possibly premeditated configuration emerges (Figure 42). It is namely possible that an unfinished bird petroglyph is standing/sitting on the back of the feline. Again, the reconstruction of the tail-end of the feline is uncertain.

Figure 40. Petroglyphs on Panel 6 at Foum Chenna 1. Photograph Copyright by Werner Pichler/Institutum Canarium (2007).

Figure 41. Petroglyphs on Panel 6 at Foum Chenna 1. Drawing Copyright by Werner Pichler/Institutum Canarium (2007).

Figure 42. Petroglyphs on Panel 6 at Foum Chenna 1. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on the photograph of Figure 40 by Werner Pichler/Institutum Canarium (2007).

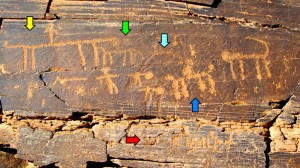

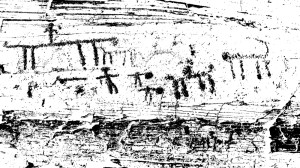

Panel 7

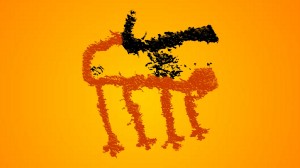

Panel 7 is an almost vertical rock face situated a short distance NE of Panel 5 (see Figure 11), NW of Panel 4 (see Figure 21) and approximately at the same height above ground level. Cracks divide the panel into three sectors (Figure 43). Besides some amorphous markings the upper segment (C) has two petroglyphs of horsemen carrying a round shield, a possible sheep and a possible dog. The left segment (B) has two rather large (possibly unfinished) markings. The petroglyph I am interested in is found in sector A, which has a number of amorphous markings, two groups of finely incised lines that have been arranged like a shower (one emerging from below the ‘belly’ of the feline), one horseman with a round shield and an uncharacteristic feline-bird combination (shown in red in Figure 44).

Figure 43. Petroglyphs on Panel 7 at Foum Chenna 1. Photo Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure 44. Petroglyphs on Panel 7 at Foum Chenna 1. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Although it is by no means certain that the feline-bird combination is intentional or even that both the feline and the bird have been manufactured by the same hand at the same time, it is worth considering the combination as a whole; as if it was manufactured by the same person with the intention to create a intimate arrangement. Importantly, there is no physical or graphical separation between the two zoomorphs; they seem to form one unit. Moreover, there is no recognisable difference in patination, although the peck markings of the feline seem to be slightly bigger and deeper and may thus have a slightly darker appearance. The feline looks to the right (to the NE), whereas the bird – that is clearly sitting/standing on the shoulder of the feline – is looking to the left (to the SW). What is also interesting is that the bird seems to exhibit its two wings that are folded (as two parallel grooves) over its back; a feature not noticed by me elsewhere at Foum Chenna.

It is uncertain what species the bird is, but it seems that the length of its wings is bigger than the usually much shorter depicted wings of an ostrich (Figure 45). Also in other rock art regions of the Sahara, for example in the Aïr Mountains of Niger (Lhote 1987: Planche 9; Fig. 310), images of winged ostriches usually display considerably small wings. For that reason I think that the bird on Panel 7 represents a bustard. If so, it probably is the Arabian Bustard (Ardeotis arabs) which may range up to 70 to 90 cm in height.

Figure 45. Possible ostrich petroglyph on a panel at Foum Chenna, southern Morocco. Photograph Copyright by Christophe Vigerie, 2011: photo 40, reproduced here with his kind permission (2014: pers. comm.).

Unfortunately, I have no clear picture of what Searight acknowledges to represent an obvious image of a bustard, even when she remarks (2001: 67) that ‘the bustard is clearly distinguishable from the ostrich by its heavier, squatter form’. She also admits that images of the bustard are fairly rare, being engraved on a few sites only in south Morocco (although she only refers to sites in Zone 5 and 7, while Foum Chenna is in her Zone 6).

The bustard is no bird of prey and thus the combination will probably not represent an attack by the bird, also because it is also hard to believe that a bustard or even a raptor would attack a wild cat like a lion or leopard. But equally it is obvious that the feline is not attacking the bird. As this feline-bird combination seems to be unparalleled in Foum Chenna and is unknown to me at other Saharan rock art sites, it will be hard to reveal the meaning of this configuration.

On the other hand, instances of humans mounting zoomorphs (mainly horses and camelids and occasionally elephants) are rather common in Saharan rock art, because they usually concern instances of riders. The riders at Foum Chenna are often represented by one single, short and straight line, or as elements shaped like a T or like a cross; in the last two cases the horizontal bars represent the arms. Therefore, combinations of anthropomorphs sitting on horses and camelids are to be expected. But a bird on a feline is surprising.

However, other unexpected combinations occur in Saharan rock art, like the petroglyph of an anthropomorph standing on an ostrich at Gouret (Lhote 1987: Planche 40; Fig. 1454), or the petroglyphs of an ostrich standing on a bovine at Aoukaré (Lhote 1987: Planche 69; Figs 138 and 139), both in the Aïr Mountains of Niger.

More distant analogies have been reported from the deserts west of the High Andes in South America. Several petroglyphs at Toro Muerto in the Majes Valley of southern Peru display the combination in which a bird, in most cases a raptor, is either directly hovering over a zoomorph or actually holding a zoomorph in its claws. In some cases it is obvious that the condor has been displayed (Figure 46). Núñez Jiménez (1986: 60) calls such combinations ‘Yawar Fiesta’, referring to a Post Colonial Andean conflict-ritual in which the condor, tied to the back of a bull, represents the Andean people and the bull the Spanish conqueror. However, Núñez Jiménez rightly argues that the much older petroglyphs of the bird-zoomorph combination have nothing to do with this Post Colonial custom. The condor, a sacred bird in Andean worldview, is regarded to convey messages between the ordinary world and the realm of the gods. Yet, the meaning of this Andean condor-zoomorph combination will remain enigmatic.

Figure 46. Petroglyphs of a condor sitting on a zoomorph on a boulder at Toro Muerto, southern Peru. Photograph Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Panel 8

In one case a petroglyph of a feline – with a relatively large, fully pecked circular head – has a row of dots arranged parallel to each side of the elongated body of the animal (Figure 47). Marcel Reine compares the style of this ‘panther’ petroglyph with similar representations in Egypt, without, unfortunately, referring to a specific site (Reine 1969: Fig. 4). A similar arrangement of dots has possibly been noticed at a feline petroglyph on a panel listed as Chenna 1 – 35 by Werner Pichler (2007 – Earlier Documentations: Fig. 1). The dots could represent symbols of power.

Unfortunately, both panels could not be located during my visit and they may have been detached, displaced and buried during the heavy torrents of 1994-1995. Panel 8 was located just below the purported archer petroglyph (see Figure 23) and just a couple of metres NE of Panel 3 (see Figure 29). The former location of Panel 8 is also traceable in a photograph by Werner Pichler (2007: Fig. 2). Panel 8 may still at Foum Chenna, but the block may also have been transported or even stolen.

Figure 47. Petroglyph of feline at Foum Chenna 1. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph by Marcel Reine (1969: Fig 4).

*

Interpretation

Undeniably the schematic style of the Libyco-Berber images often inhibits the unambiguous identification animal species. What we ‘recognise’ as a feline may well have been intended to represent another type of animal. For instance, Alain Rodrigue illustrates two Libyco-Berber petroglyphs (2002: Fig. 20-5), which he interpreted as ‘Piéton et félin’, which, for matters of convenience, I translate here as ‘anthropomorph and feline’. However, the animal definitely does not look like the typical feline representations of the Upper Drâa valley that are characterised by a rather long body ending in a round head (without ears) and a long up-curving tail. In my opinion the zoomorph (Figure 48) could equally represent a dog, a fox, a jackal or even a horse.

Figure 48. Petroglyph of a Libyco-Berber zoomorph. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on a drawing by Alain Rodrigue (2002: Fig. 20-5).

It seems that – in general – feline petroglyphs are rare in the Libyco-Berber rock art sites of the Anti Atlas. Therefore their above average occurrence at Foum Chenna may be significant. Although I have not seen any of the three other Libyco-Berber rock art sites in the mountain ridge, it seems that at least in the pass of Assif Ouiggane feline petroglyphs also occur (see Figure 22), also possibly more than average. I have no record of feline petroglyphs at the petroglyph site of Chaba el Beida, but a photograph taken by Marcel Reine at Djorf el Rhil might show two petroglyphs of possible felines (1969: Fig. 17), although the characteristic position of the tail hovering over the back seems to be lacking (possibly weathered off or simply invisible in the photo?).

It may now be important that Djorf el Rhil is not regarded by Marcel Reine to be on a through route, but instead represents a meeting place (1969: 43). Perhaps it is associated with one of the several temporary habitation sites in the area, as may be evidenced by complex of ruins directly at the foot of the cliff at Djorf el Rhil (visible with Google Earth). Perhaps also Chaba el Beida is not a on a (significant) through route. On the other hand, Assif Quiggane and especially Foum Chenna are located on routes regarded to be important because they lead to the mineral-rich Grara region. For that reason both passes seem to have been heavily guarded and controlled by fortifications (Searight 2001: 202). It is now possible that especially the feline images once served as warning signs or as powerful symbols controlling access to the pass. If this is indeed the case, then it is useful to look for possible parallels.

In Morocco there are more Libyco-Berber rock art sites where images of felines have been reported, but it seems that generally the number of feline petroglyphs at those sites is low (Searight 2001: Appendix 11). For instance, at Jebel Rat in the High Atlas the site of Tizi n’Tirlist (Zone 3 – HA5) several Libyco-Berber petroglyphs have been recorded, including a feline hunt scene (Searight 2001: 196; Fig. 11d). It may be important that this site is also on or near a pass (Searight 2001: 85). Another petroglyph at Jebel Rat (at a site called Tizi n’Tirghist, which may be the same as Tizi n’Tirlist) may be interpreted as the stretched-out skin of a feline, the species recognisable by the cupules representing the toes of the animal (Manard 2012: internet). It is not certain however if this ‘skin’ petroglyph is of Libyco-Berber manufacture. The petroglyph and especially the five dots at the paws are more reminiscent of the High Atlas rock art style.

Interestingly, besides Foum Chenna I only know of one significant exception. Susan Searight refers to the recording by Alain Rodrigue of at least 23 feline petroglyphs at the Libyco-Berber rock art site of Ram Ram (Zone 1 – NC11), just north of Marrakech (2001: 292). Taking into account possible misinterpretations, this means that of the total of 254 identifiable petroglyphs at Ram Ram a percentage of roughly 9% concerns felines. This percentage is remarkably higher than the percentage of feline petroglyphs at Foum Chenna. Crucially, Searight (2001: 192) remarks that Ram Ram is a site in a strategic position and on an important through route. She also remarks that Rodrigue noticed that petroglyphs of camelids are missing at Ram Ram. This may be an indication that (most of) the Libyco-Berber images at Ram Ram are older than the introduction of camelids in this area. This hypothesis may imply that the feline petroglyphs at Foum Chenna also date from (only?) the Horse Period.

Based on these observations I would like to propose a brief and simplified chronology for Foum Chenna rock art. In this respect I prefer to follow Marcel Reine’s suggestion that at Foum Chenna the fully pecked, deeply patinated zoomorphs (Figures 19 and 20) belong to the earliest rock art tradition at Foum Chenna; his ‘Metal Age’ (Reine 1969: 39); a pre-Libyco-Berber Period. Perhaps the large, outlined petroglyphs of ostriches (and possibly some other petroglyphs not yet identified as very ancient) also belong to this first phase (Figure 17 and 18).

The following rock art phase is the Libyco-Berber Period introducing the horseman armed with a round shield and (occasionally depicted at Foum Chenna) a lance (see video; fourth part). Also the enigmatic Libyco-Berber inscriptions (the earlier generation of the Tifinagh inscriptions) belong to this phase. Susan Searight roughly dates this period from 1000 B.C. to A.D. 1000 (2001: Table 30). This is a very long period, which also explains subtle differences in style. It can be divided into two phases. The first phase starts with the introduction of the domesticated horse; the Horse Period (roughly from 1000 B.C. to A.D. 0). Camelids were unknown in northern Africa during that phase. Then, around 500 B.C., camelids were introduced into the Eastern Sahara and over time representations of camelids (actually only of the dromedary) also appeared in the rock art repertoire of the Western Sahara; the Camel Period (around A.D. 0 to present).

I now would like to propose that also at Foum Chenna the feline petroglyphs are part of the Horse Period iconography. One argument could be the fact that feline petroglyphs are often rather deeply patinated, especially the scene on Panel 3 (see Figure 29). Another reason is the hard to prove idea that existing petroglyphs of zoomorphs (mainly horses or felines) may have been changed into camelids by adding a hump onto the back. This may have been done with feline D on Panel 1 (see Figure 27) that may have been re-pecked (in contrast with the felines A, B and C in Figure 27 that seem to have been hacked). Another possible example is marked with a dark-blue arrow in Figure 17. Likewise felines may have been changed into horses carrying a rider as may be the case with the possible (!) feline B in Figure 16, feline B in Panel 3 (see Figures 29 to 33 and the felines of Panel 4 (see Figures 35 to 37) and Panel 6 (see Figures 40 to 42). It is also possible that images of horses were changed into camelids shortly after the introduction of the camelid into the area. An example may be the petroglyph of a zoomorph with a remarkably short neck which looks more like a horse when depicted without the hump on the back (Figure 49). Remarkably, the zoomorph has also a (smaller) ‘hump’ below the belly. This smaller hump may have been executed to erase the feet of a rider, while simultaneously the larger hump on the back obliterated the rider. Unfortunately this hypothesis cannot be proven anymore.

Figure 49. Zoomorphic petroglyph at Foum Chenna 1 that might depict a horse that has been altered into a camelid. Drawings and photograph Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Taking into account the absence of camelid petroglyphs at the Libyco-Berber rock art site of Ram Ram – north of the High Atlas – it may well be worthwhile to more thoroughly investigate the possibility that at Foum Chenna the image of the feline indeed only belongs to the Horse Period as well. Moreover, this paper illustrates that – possibly – zoomorphic images at Foum Chenna once were re-designed in order to represent other species. This practice may be compared with the lion petroglyph of Ouan Houas that seems to have had a head added (Figure 50). I therefore recommend that future research of Libyco-Berber petroglyphs, especially at Foum Chenna and neighbouring sites, also systematically investigates the possibility that existing images of zoomorphs once were changed into another species.

Figure 50. Petroglyph of a lion at Ouan Houas, Mertoutek, Haggar, Algeria. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on a rubbing by Ernesto Oeschger (2004: 19).

*

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Mr. H. J. Ulbrich of the Institutum Canarium for his kind permission to use and publish some of the graphic material from the LBI-Project (Pichler 2007): International Project for the application of an on-line database for the storage and analysis of Libyco-Berber inscriptions of the Canary Islands and Northern Africa (sponsored by the Institutum Canarium). The material provided in the LBI-web site mainly belongs to the legacy of the late Prof. Werner Pichler. I am also grateful for the sympathetic permission of Mr. Christophe Vigerie to use and publish some of his photographs from his photographic collection (Picasaweb 2011). I also thank Prof. Lionel Galand for inspecting and judging photos with possible lines of Libyco Berber inscriptions. However any interpretation or graphical presentation in this paper is my responsibility only. Last but not least I thank my wife Elles for ongoing and much appreciated support in the field and at home.

*

Bibliography

Coulson, D. and A. Campbell. 2001. African Rock Art. Paintings and engravings on stone. New York.

Lhote, H. 1987. Les gravures du pourtour occidental et du centre de l’Aïr. Éditions Recherche sur les Civilisations; Memoire no. 70. Paris.

Núñez Jiménez, A. 1986. Petroglifos del Perú. Panorama mundial del arte rupestre. 2da. Ed. PNUD-UNESCO – Proyecto Regional de Patrimonio Cultural y Desarrollo, La Habana, Cuba.

Oeschger, E. 2004. Sahara Algeria; Rock Art in Oued Djerat and the Tefedest Region. Adoranten 2004; pp 5 – 19.

Pichler, W. 2000. The Libyco-Berber inscriptions of Foum Chenna (Morocco). Sahara 12. Segrate/Italia. 176-178.

Pichler, W. 2007. LBI-Project. International Project for the application of an on-line database for the storage and analysis of Libyco-Berber inscriptions of the Canary Islands and Northern Africa (sponsored by the Institutum Canarium).

Reine, M. 1969. Les gravures pariétales libyco-berbères de la haute vallée du Drâa. In: Antiquités africaines (PDF), Vol. 3; pp 35 – 54. Persee.

Rodrigue, A. 2002. Préhistoire du Maroc. La Croisée des Chemins, Casablanca.

Searight, S. 2001. The Prehistoric Rock Art of Morocco. A Study of its extension, environment and meaning. PhD. Thesis. Bournemouth University.

Simoneau, A. 1971. La région rupestre de Tazzarine. Documents nouveaux sur les chasseurs-pasteurs (1). Revue de Géographie du Maroc. Nr. 20 :107-120.

Simoneau, A. 1974. Les cavaliers du Haut Drâa. Bulletin d’Archéologie Marocain. t. VIII (1968-72), 27-36.

Simoneau, A. 1976. Les rhinocéros dans les gravures rupestres du Dra-Bani. In: Antiquités africaines (PDF), Vol. 10; pp. 7-31. Persee.

Simoneau, A. 1977. Catalogue des sites rupestres du Sud-Marocain. Rabat.

Skounti, A. et al.. 2003. Tirra – Aux origines de l’écriture au Maroc. Etudes et Recherches No.1. CEALPA.

Van Hoek, M. 2007. Toro Muerto, Perú. Posibles alteraciones prehistóricas en detalles de petroglifos. In: Rupestreweb.

*

Websites featuring Libyco-Berber petroglyph art

Lamnay, I. 2014. Gravures NO Zagora (Site A).

Lamnay, I. 2014. Gravures NO Zagora (Site C).

Van Hoek, M. 2014. The Felines of Foum Chenna. YouTube.

Vigerie, C. 2011. Gravures Nord de Zagora.

YouTube. 2012. Foum Chenna.

*

*

Leave a Reply