This paper discusses several aspects of rock art research in general, using the status of rock art research in the Cuyo region of western Argentina as a pilot study. A number of protected and unprotected rock art sites will be discussed, focussing on four interrelated issues: Issue 1: Have the locations of rock art sites correctly been published? Issue 2: Should rock art sites be accessible for all? Issue 3: Should the location of rock art sites be revealed or not? Issue 4: Do only academics have the right to publish information about rock art?

by Maarten van Hoek

.

Rock Art at Ischigualasto, and more …

Discriminatory Exclusivity Regarding Rock Art Research in Argentina

Maarten van Hoek – rockart@home.nl

.

∞

A young Peruvian shaman, Amado Quispe, once explained the ancient yet still revered Andean concept of Yanantin as follows: For us, Yanantin doesn’t focus on the differences between two beings. That is what disconnects them. Instead, we focus on the qualities that brought them together. One on its own can’t hold everything, can’t take care of everything. Not only are they great together, but they need to be together. When there is another, it represents extra strength for both. (Webb 2012: 75).

∞

.

PART I

Rock Art at Ischigualasto, and more …

.

Introduction

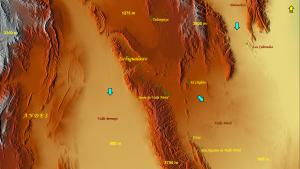

Cuyo is the name of a large district in western Argentina which includes (among others) the Province of San Juan. Since 1988 the Province of La Rioja has been added to “la Región del Nuevo Cuyo”. In this paper the term Cuyo refers to only a small part of the two neighbouring Provinces of San Juan and La Rioja; the Study Area of this paper (Figure 1). It still is a large area – roughly 120 km from north to south – in which the National Park of Talampaya and the Provincial Parks of El Chiflón and Ischigualasto (also called Valle de la Luna) are major tourist attractions. All three parks are protected by Argentinean law because of their outstanding natural beauty. More important in the scope of this paper is the fact that also many rock art sites have been recorded in those three parks. However, also outside those parks many more rock art sites have been reported in Cuyo, like the Banda Florida, Palancho and the valley of the Río San Agustín in the Sierra de Valle Fértil.

Figure 1. The Study Area. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth Relief Maps.

Figure 1. The Study Area. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth Relief Maps.

In this paper a number of protected and unprotected rock art sites in the Study Area – from Talampaya in the north to San Agustín de Valle Fértil in the south – will be discussed, mainly focussing on four interrelated issues that in fact not only concern rock art research in Argentina, but also the rock art research in Chile, Peru, Bolivia etc, etc. Issue 1: Have the locations of rock art sites in the Study Area correctly been published? Issue 2: Should rock art sites be accessible for all? Issue 3: Should the location of rock art sites be revealed or not? And finally, Issue 4: Do only academics have the right to publish information about rock art?

First five rock art regions will be discussed from north to south (Talampaya, Ischigualasto, Sierra de Valle Fértil, El Chiflón and San Agustín de Valle Fértil), focussing on the location details, mainly in relation to the four issues. Then the four issues will be discussed in more detail.

To visually support the content of this paper I created a YouTube video providing the (extra) graphical information. This video – which is in Spanish – contains numbered and unnumbered illustrations. The numbering of the illustrations in this paper and in the video is the same. However, not all illustrations that appear in the video, have been included in this paper. The illustrations that only appear in the video are referred to as Video only Figure in the text and in captions. Only one illustration, which appears in the paper, does not appear in the video. Therefore a combined use of paper and video is strongly recommended. All numbered illustrations, also the illustrations that only appear in the video, have a caption in this paper, revealing the source of the illustrations (in combination with the bibliography). All graphic material in this paper and in the video has been digitally enhanced by me and all drawings – based on various sources – have been adapted by me as well.

You can watch the video using the graphical link below, or, alternatively, you may prefer to click the following link so that the video appears next to the TRACCE publication.

.

∞

Talampaya

One of the most impressive landscapes that I have seen in Southern America is found in the National Park of Talampaya, La Rioja. Sheer vertical cliffs of pink-red sandstones rise about 150 m above the sandy floor of the canyon and at other spots in the park towering pinnacles literally dwarf the visitor. The park is also known for its rock art (examples), which is mainly (only?) found at the left (south) bank of the Río Talampaya, which is completely dry for most of the time and thus conveniently serves as a way of access.

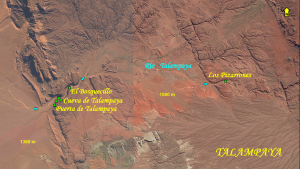

In the literature that I have available the following names of petroglyph sites occur: Puerta de Talampaya, Aguas Arriba, El Bosquecillo, Los Guanaquitos and Los Pizarrones. At the moment (2015) most sites are accessible for the tourist and an official guide from the park will gladly show the interested visitor those sites. In none of the publications that are available to me is a map that indicates the precise location of those sites, except for one site (though without further geographical context). Yet, in the field as well as at home I have gathered information about the location of the rock art sites in Talampaya. With this information I constructed a map of the area showing the locations of the rock art sites in the park (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Map of Talampaya rock art sites. All locations of rock art sites (indicated by green squares) are approximated. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Figure 2. Map of Talampaya rock art sites. All locations of rock art sites (indicated by green squares) are approximated. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Puerta de Talampaya is the largest petroglyph site in the park and a selection of photos of the petroglyph panels is given in the video. The site is located at the south side of the impressive west-facing entrance of the canyon (Figure 3). Yet, there is more rock art in the park than the visitor is allowed to see. The first day I arranged a tour with a mini-bus through the canyon, which also stops at the rock art site of Puerta de Talampaya. This site is actually (much?) larger than what is shown to the public. Only the northern part (with a fenced off pathway of 350 m in length) is ‘accessible’ for the visitor (and one is not allowed to go beyond the fence, although the first day I was kindly allowed to use the IFRAO scale beyond the fence). However, further south (many?) more petroglyph rocks have been recorded (Video only Figure 3A). Unfortunately, this southern part is a restricted area that is not open to visitors. Yet, there seem to have been individuals who – with or without permission – have photographed petroglyphs that definitely are located in the prohibited area. I explicitly asked the guide if we could visit this prohibited area, but permission was quite abruptly refused without any explanation.

Figure 3. Map of Puerta de Talampaya rock art panels. The locations of some of the rock art panels (indicated by green squares) are approximated. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Figure 3. Map of Puerta de Talampaya rock art panels. The locations of some of the rock art panels (indicated by green squares) are approximated. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Video only Figure 3A. Sketch of a petroglyph in the prohibited zone of Puerta de Talampaya. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photo by Ricardo González (2013?).

The second day I arranged for a guided walk and at that occasion the guide showed the group of visitors a small rock art site just inside the gorge. This may be the site called Aguas Arriba (Video only Figure 4). It has only a few petroglyph panels on large boulders (some petroglyphs are shown in the video). The tour continued towards a small and low cave (see video) some 150 m to the ESE of Site B. At one spot, at about two meters above the valley floor, I noticed a faint and isolated petroglyph on the enormous vertical wall of the canyon (see video). I mentioned it to the guide, who looked very surprised as if he had no knowledge of that specific petroglyph. As I could find no reference to this petroglyph in any of the publications that I have available, I take the liberty to call this site, which is located some 20 to 30 metres west of the cave, Cueva de Talampaya. El Bosquecillo is the same site as El Jardín Botanico, which is located at about 1 km NE of the entrance (Figure 5). There is only one petroglyph panel and a boulder with ‘morteros’. The location of Los Guanaquitos could not be found. It may well be an alternative name for one of the other petroglyph sites in Talampaya.

Video only Figure 4. Map of the Aguas Arriba (?) and Cueva de Talampaya rock art panels. All locations of rock art panels (indicated by green squares) are approximated. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Figure 5. Map of the El Bosquecillo rock art panel. The location (indicated by a green square) is approximated. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Figure 5. Map of the El Bosquecillo rock art panel. The location (indicated by a green square) is approximated. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

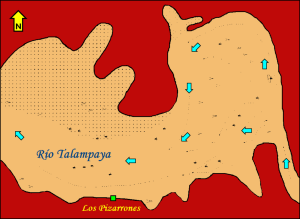

Each day, before taking off for one of the excursions I asked several officials/ guides at the Visitor Centre if I could visit Los Pizarrones, but also this request was without success, because, as the officials said, there were no excursions to that area anymore. Again, there was no explanation, even after having explained my special interest in rock art. Also, they were not willing to say anything about the location. Argentinean archaeologist Juan Schobinger briefly described Los Pizarrones (not mentioning this name however) and stated that the site was located at 5 km from Puerta de Talampaya (1966: 4). This proved to be wrong.

Much later, back home, I managed to track down the probable location of Los Pizarrones in Google Earth (Figure 6). With some trouble I could trace the site in Google Earth, using a rough sketch of the location (Figure 6B) in a paper by Lorena Ferraro, Cecilia Pérez Winter and Christian Mancino describing the vulnerability of the rock wall with petroglyphs (Ferraro et al. 2009). Los Pizarrones proved to be located some 12 km east of Puerta de Talampaya (see Figure 2). A modified and animated sketch of the petroglyphs on the north facing cliff is shown in the video (Video only Figure 6A).

Figure 6. Map of the Los Pizarrones rock art site. Location (indicated by a green square) is approximated. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Figure 6. Map of the Los Pizarrones rock art site. Location (indicated by a green square) is approximated. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Video only Figure 6A. Animated sketch of the petroglyphs at Los Pizarrones. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on an illustration in Ferraro et al. (2009: Fig. 5).

Figure 6B. Sketch of the location of the Los Pizarrones petroglyph site. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Ferraro (2009: Fig. 3).

Figure 6B. Sketch of the location of the Los Pizarrones petroglyph site. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Ferraro (2009: Fig. 3).

To my surprise it proved – after contacting Talampaya in 2015 via email – that all tours included a visit to Los Pizarrones after all, as I received the following response: Le comento que en todas nuestras excursiones Uds. podrán visitar los Petroglifos ya que dicho sector es uno de los más relevantes de nuestro Parque. As I wondered if indeed their email referred to Las Pizarrones and not to Puerta de Talampaya, I emailed them again – attaching a map of the park (Figure 2) with Los Pizarrones marked on it – to specifically ask for a confirmation. From their kind reaction it proved that nowadays Los Pizarrones is truly accessible for every (guided) visitor, which indeed is a very positive policy.

In the meantime I hoped that also at Ischigualasto the policy and attitude has changed.

Alas, in vain!

∞

Ischigualasto

Some 40 km due south of Puerta de Talampaya is the entrance to Ischigualasto Provincial Park. Though – in my opinion – less impressive as Talampaya, this park houses several most interesting geological rock formations, a number of rock art sites and possibly a few simple circular/oval geoglyphs (Guráieb et al. 2007: Fig. 2; Guráieb et al. 2014; providing the following coordinates S. 30° 7′ 57.4″ and O. 67° 52′ 12.8″).

However, when I arrived at Ischigualasto Visitor Centre in 2010 and asked if I could arrange a trip to the rock art sites in the park, I received a very unpleasant answer. To my astonishment several of the officials/guides (Guías Guardaparques) stated that there was no rock art in the park. Even when I repeatedly explained – again at two occasions – that I was convinced that there was definitely rock art in the park, they maintained their lies and insisted that there was no rock art at Ischigualasto. And then there is nothing one can do. Consequently I saw not a single petroglyph during my two guided excursions through Ischigualasto.

Why was I convinced that the park-officials were lying to me? Because – before travelling to Argentina in 2010 – I read a paper about Ischigualasto rock art written by two respected Argentinean archaeologists, María Mercedes Podestá and Diana Susana Rolandi (Podestá and Rolandi 2001), that was published in 2001. In their paper was a map of Ischigualasto (Fig. 4) indicating at least three separate rock art sites (Agua de la Peña, Piedra Pintada and El Kiosco) and a few illustrations of some petroglyph panels. On top of that, in 2005 archaeologists María Mercedes Podestá, Diana Susana Rolandi and anthropologist Mario Sánchez Proaño published an informative book about rock art in the NW of Argentina in which a photograph of a petroglyph boulder at the Piedra Pintada site in Ischigualasto appears (Podestá et al. 2005: Plate 28).

After my visit in 2010, several other publications (both on paper and on the internet) affirmed the existence of rock art at Ischigualasto. Therefore, rock art was definitely known to exist in the park – thus also in 2010 – and I am convinced that the officials at the Visitor Centre at Ischigualasto knew about it (more about this issue later on). Why did they lie to me? To protect ‘their’ rock art or to prevent a foreigner from visiting rock art at Ischigualasto? In any case it is unacceptable that employees at Ischigualasto, a park that boasts to be World Heritage (Patrimonio de la Humanidad), use this method. I rather received the answers the Talampaya officials gave me, than being lied to.

But there are more issues about Ischigualasto rock art than only accessibility, as it proves that information about the location of the rock art sites at Ischigualasto in works published by academic (Argentinean) rock art researchers is often confusing, vague, conflicting and sometimes incorrect. At the moment at least six (possibly 7) different rock art sites (depending on the definition of a rock art site) have been recorded at Ischigualasto. Most sites are located NNW of the Visitor Centre. From north to south and numbered in Figure 7: 1): a new (?) site called La Chilca Norte by me; 2): Quebrada de La Chilca; 3): El Salto; 4): Piedra Pintada; 5): Agua de la Peña; 6): (El) Kiosco (or Kiosko) and 7): Agua de las Marcas. There are more rock art sites outside the park and SE of the Visitor Centre, but those will only be briefly discussed in another section. The six/seven rock art sites of Ischigualasto will now be discussed in ‘random’ order.

Figure 7. Map of Ischigualasto rock art sites. All locations of the geoglyphs (yellow square) and rock art sites (green squares) are approximated. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Figure 7. Map of Ischigualasto rock art sites. All locations of the geoglyphs (yellow square) and rock art sites (green squares) are approximated. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

SITE 5: Agua de la Peña: To start with, the site of Agua de la Peña was described in a paper by María Mercedes Podestá, Diana Susana Rolandi, Anahí Re and Oscar Damiani (Podestá et al. 2003a), of which a curtailed version was published in the NAyA web site (Noticias de Antropología y Arqueología. The NAyA web page (Podestá et al. 2003b) does not contain illustrations but revealed that Agua de la Peña is located at S. 30° 5′ 21.3″ and O. 67° 55′ 57.8″. The same coordinates for Agua de la Peña have also been published by Diana Susana Rolandi, María Mercedes Podestá, Ana Gabriela Guráieb, Anahí Re and AixaVidal (Rolandi et al. 2005: 107).

However, the 2003-paper (Podestá et al. 2003a) was published again in 2006 by María Mercedes Podestá, Diana Susana Rolandi, Anahí Ré, María Pía Falchi and Oscar Damiani (Podestá et al. 2006). The map in the 2006-version (2006: Fig. 5) showed the location of Agua de la Peña at the same location as indicated by the coordinates in 2003 (and 2005). This petroglyph site proved to be only 290 meters SE of the tourist track leading to the main attraction of Ischigualasto: the rock formations of ‘El Submarino’ (see video), which are located only 1450 m to the NW of the rock art site (Figure 8). Without realising it, I passed this petroglyph site in the park at a very short distance and it would thus have been no problem at all for a guide to show me the petroglyphs at Agua de la Peña (Video only Figure 8A) and at El Kiosco (which is only located a short distance to the SSE – see Figure 8).

Figure 8. Map of the rock art sites very near the tourist track leading to ‘El Submarino’, Ischigualasto. The red square roughly marks the location of Kiosko as incorrectly stated by Podestá and Rolandi (2001: 66). Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Figure 8. Map of the rock art sites very near the tourist track leading to ‘El Submarino’, Ischigualasto. The red square roughly marks the location of Kiosko as incorrectly stated by Podestá and Rolandi (2001: 66). Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Video only Figure 8A. Part of the petroglyph panel at Agua de la Peña, Ischigualasto. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Re et al. (2010: Fig.10).

SITE 6: Kiosco: Now it is getting complicated. According to María Mercedes Podestá and Diana Susana Rolandi (Podestá and Rolandi 2001) the petroglyph site of Kiosco is ‘localizado a 2 km al este de Agua de la Peña’ (2001: 66), although their map (2001: Fig. 4) shows Kiosko to the SE and not to the east of Agua de la Peña. Also the 2005 publication (Rolandi et al. 2005: 105) repeats that Kiosco is found 2 km east of Agua de la Peña (a spot marked with a red square in Figure 8). Thus, in at least two scientifically presented papers Argentinean academics offer confusing information, which, moreover, proves to be incorrect.

Fortunately, a publication by Ana Gabriela Guráieb, Diana Carro and Marcos Rambla (Guráieb et al. 2014) provided the coordinates of S. 30° 6′ 16.3″ and O. 67° 55′ 27″ for a site they called El Kiosko, which proved to be a spot 1900 m SSE of Agua de la Peña! As Ana Gabriela Guráieb, Diana Carro and Marcos Rambla mention the existence of petroglyph art at that site (Guráieb et al. 2014) there is no doubt that it concerns the same site as Kiosco. Guadalupe Romero and Anahí Re (Romero and Ré 2013: Fig. 4) published a photo and a drawing of one of the rock art panels at Kiosco (Video only Figure 8B).

Video only Figure 8B. Petroglyphs on Panel 1A at Kiosco, Ischigualasto. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek based on Romero and Ré (2013: Fig. 4).

As I was not allowed to visit any of the rock art sites in the park, I am not able to tell which publication provided the correct information about the location of Kiosco (or any other site that I did not visit), but I think the location published by María Mercedes Podestá and Diana Susana Rolandi (2001) is incorrect.

SITE 7: Agua de las Marca: The historic rock art site of Agua de las Marcas was also mentioned in the paper by María Mercedes Podestá, Diana Susana Rolandi, Anahí Re and Oscar Damiani (Podestá et al. 2003a). The NAyA web page (Podestá et al. 2003b) revealed that Agua de las Marcas is located at S. 30° 10′ 50″ and O. 67° 53′ 44.7″. The map in the 2006-version (Podestá et al. 2006: Fig. 5) showed the location of Agua de las Marcas at more or less the same location as indicated by the coordinates in 2003. It is found 5.3 km WSW of the Visitor Centre and only 840 m NE of the main asphalt road – RN-150 – from Baldecitos to Chile (Video only Figure 9).

Video only Figure 9. Location of the rock art site at Agua de las Marcas, Ischigualasto. Location (indicated by a green square) is approximated. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

SITES 3 and 4: Piedra Pintada – El Salto: As is often the case in South America, the name Piedra Pintada (painted rock) does not always refer to a panel with rock paintings, but often to a rock with only petroglyphs, which is also the case at Ischigualasto. María Mercedes Podestá, Diana Rolandi, Anahí Ré, María Pía Falchi and Oscar Damiani (Podestá et al. 2006: 176) mention that the site of Piedra Pintada is located 18 km from Agua de Marcas (as the crow flies, without providing any bearing). Piedra Pintada is in most publications described by Argentinean archaeologists together with El Salto, and – even more confusingly – sometimes also together with the site of Quebrada de La Chilca. In my opinion the limits between those three rock art groups are most ambiguous. Moreover, the three sites do not seem to have their own numbering of boulders/panels each, which again is most confusing.

There are now two serious inconsistencies regarding location details published by Argentinean scientists. First of all, María Mercedes Podestá, Diana Rolandi, Anahí Re and Oscar Damiani (Podestá et al. 2003b) revealed in the NayA web page that Piedra Pintada is located at S. 30° 01′ 53″ and O. 67° 58′ 53″, which indeed is a spot 18 km NNW of Agua de las Marcas. However, at that spot there is definitely no match for the sketch of the Piedra Pintada – El Salto complex provided by María Mercedes Podestá, Diana Susana Rolandi, Anahí Ré, María Pía Falchi and Oscar Damiani (Podestá et al. 2006: Fig. 6). The only possible match that I could find with Google Earth is 25 km to the NNW of Agua de las Marcas, but this spot is not the site of Piedra Pintada or El Salto; it is the main concentration of rock art in the Quebrada de La Chilca. Moreover, their sketch (Figure 10) proved to be most inaccurate when I finally could spot the true location of the southern end of the Piedra Pintada complex in Google Earth, which is marked by an isolated rock formation called Promontorio Piedra Pintada (Figure 11). The coordinates of the summit of this promontory in Google Earth are S. 30° 1′ 41.81″ and W. 67° 58′ 41.53″.

Figure 10. Sketch (incorrect – see Figure 11) of the rock art complexes at Piedra Pintada – El Salto, Ischigualasto. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on the incorrect sketch in Podestá et al. (2006: Fig. 6).

Figure 10. Sketch (incorrect – see Figure 11) of the rock art complexes at Piedra Pintada – El Salto, Ischigualasto. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on the incorrect sketch in Podestá et al. (2006: Fig. 6).

Figure 11. Factual location of the rock art complexes at Piedra Pintada – El Salto, Ischigualasto. All rock art locations (indicated by green squares) are approximated. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Figure 11. Factual location of the rock art complexes at Piedra Pintada – El Salto, Ischigualasto. All rock art locations (indicated by green squares) are approximated. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Secondly and more confusingly, in an earlier publication María Mercedes Podestá and Diana Susana Rolandi (Podestá and Rolandi 2001) also state that Piedra Pintada is located about 18 km from Agua de la Peña (again without any bearing). However, Piedra Pintada (El Promontorio) is only 8 km NNW of Agua de la Peña, while at 18 km NNW of Agua de la Peña is the dry river bed of the Quebrada de la Chilca. But at that spot I do not know of any petroglyph site (however, there may be a rock art site at 19 km NW of Agua de la Peña (which will be discussed further down). Are you still with me? It proves that much conflicting and thus obviously incorrect information has been published by several respected Argentinean academic archaeologists.

Why am I convinced that Promontorio Piedra Pintada is located at the spot 8 km NW of Agua de la Peña without ever having been there? Two publications, one by María Mercedes Podestá, Anahí Re and Guadalupe Romero Villanueva and a second by Guadalupe Romero Villanueva (Podestá et al. 2011: Fig. 2; Romero Villanueva 2012: Fig. 3) included a rather detailed map of the whole length of the Piedra Pintada – El Salto – Quebrada de la Chilca rock art complex. The Piedra Pintada – El Salto Section proved to be much different to the sketch (see Figure 10) previously published (Podestá et al. 2006: Fig. 6). But, together with all other pieces of information, the situation finally became more transparent.

It proved that the rough sketch by María Mercedes Podestá, Diana Susana Rolandi, Anahí Ré, María Pía Falchi and Oscar Damiani (see Figure 10) is inaccurate and even incorrect. Their sketch is also confusing as – for instance – their Bloque 16 does not appear on the map, while Bloque 17 is marked on the north side of the quebrada, but in another map it appears on the south side, together with Bloque 16 (Podestá et al. 2011: Fig. 2). I therefore include Google Earth maps with the hopefully correct locations of the petroglyph boulders/panels at the Piedra Pintada – El Salto complex (Figure 11 and Video only Figure 12). In this respect I emphasise again that I have not visited any of those sites and the locations as marked on my maps (based on publications by Argentinean academics) may therefore be inaccurate, incomplete (where are Bloques 1, 2, 3 and 42?) and even incorrect.

Video only Figure 12. Detailed location map of the rock art complexes at Piedra Pintada – El Salto, Ischigualasto. All rock art locations (indicated by green squares) are approximated. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

The same confusion goes for the extension of the Piedra Pintada / El Salto site. María Mercedes Podestá, Diana Susana Rolandi, Anahí Ré, María Pía Falchi and Oscar Damiani (Podestá et al. 2006: 176) state that ‘Estos bloques, que suman en total 41, se extienden a lo largo de 3.5 kilómetros hasta la zona denominada El Salto …’, while earlier María Mercedes Podestá, Diana Susana Rolandi, Anahí Re and Oscar Damiani (Podestá et al. 2003b) state that ‘Los bloques se ubican a lo largo de ambas márgenes del río La Chilca hasta el sector denominado El Salto a lo largo de aproximadamente 1 km, …’. Finally, Anahí Ré, María Mercedes Podestá and Diana Susana Rolandi stated that: ‘ … los bloques de Piedra Pintada-El Salto (PP-El Salto) (Figura 3), que constituyen una localidad arqueológica, se disponen a lo largo de dos kilómetros en ambas márgenes… (Re et al. 2009: 420). Thus, according to respected Argentinean archaeologists the complex extends over 1, or 2, or 3.5 km. It proves that they offer, again, much conflicting information. According to Google Earth the complex extends from El Promontorio to El Salto for about 3.7 km, following the course of the dry river bed (2.7 km as the crow flies). In the video a small selection of images showing the variety of petroglyphs at Piedra Pintada has been included (Video only Figures 12A, B, C and D).

Video only Figure 12A. Petroglyphs on ‘Bloque’ 1 at Piedra Pintada, Ischigualasto. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Re et al. (2009: Fig. 13).

Video only Figure 12B. Historic petroglyphs at Piedra Pintada, Ischigualasto. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek based on Rolandi et al. (2009: Fig. 3).

Video only Figure 12C. Petroglyphs on ‘Bloque’ 12 at Piedra Pintada, Ischigualasto. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Podesta et al. (2006: Fig. 7).

Video only Figure 12D. Petroglyphs on Panel 2A at Piedra Pintada, Ischigualasto. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Romero and Re (2013: Fig. 6).

SITE 2: Quebrada de La Chilca: This site should not be confused with another petroglyph site in Cuyo called La Chilca, which is said to be located roughly ‘20 km from Villa Union’. In the publications that I have available, all maps located Quebrada de La Chilca to the NW of Piedra Pintada (Podestá et al. 2006: Fig. 5; Re et al. 2009: Fig. 2; 421). The map by Diana Susana Rolandi, Ana Gabriela Guráieb, María Mercedes Podestá, Anahí Ré, Rodolfo Rotondaro and Rodrigo Ramos (Rolandi et al. 2003: Fig 1) – as published in the PDF available on the internet – is extremely vague and of no scientific use at all. So, where is Quebrada de La Chilca located? The map published by Guadalupe Romero Villanueva (Romero Villanueva 2012: Fig. 3) seems to provide the most reliable details (Video only Figure 13).

Video only Figure 13. Detailed location map of the rock art complexes in the Quebrada de La Chilca, Ischigualasto. All locations (indicated by green squares) are approximated. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Moreover, there is a photograph on the internet the caption of which reads ‘Barrancas Coloradas en El Salto’. I agree, the great majority of the Ischigualasto photos uploaded onto Google Earth are in the incorrect position. However, the man who posted this photo either has knowledge of the area (he knew the name of El Salto, even if incorrectly applied) or he was accompanied by someone (an official from the park?) who possibly provided the name of El Salto. The man probably used GPS to be able to upload the photo onto the correct location (S. 29° 58′ 42.35″ and W. 68° 1′ 40.29″). Interestingly, his photo is almost the same as the one published by María Mercedes Podestá, Diana Susana Rolandi, Anahí Ré, María Pía Falchi and Oscar Damiani (Podestá et al. 2006: Lámina 1a), which proves that the man posted his photo at the correct location. But most likely this petroglyph site is not El Salto.

Another photo – uploaded by the same man – with the caption ‘marcas de un pasado lejano…’ shows the same petroglyph boulder as has been illustrated by María Mercedes Podestá, Diana Susana Rolandi, Anahí Ré, María Pía Falchi and Oscar Damiani (Podestá et al. 2006: Lámina 1d). The spot where their photo was taken proves to be located at S. 29° 58′ 38.34″ and W. 68° 1′ 41.22″, while the caption of Lámina 1d reads ‘Bloque 52 de Quebrada de La Chilca’. The rock proved to be one of complex of petroglyph boulders at the extreme northern end of the Quebrada de La Chilca site (according to Podestá et al. 2011: Fig. 2). Video only Figure 13A shows one of the other petroglyph panels at this complex.

Video only Figure 13A. Petroglyphs on ‘Bloque’ 50 at Quebrada de La Chilca, Ischigualasto. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photo in Romero and Re (2013: Fig. 5).

SITE 1: La Chilca Norte: However, there is possibly another, (still?) unrecorded petroglyph site NW of the extreme northern end of the Quebrada de La Chilca site (Figure 14). The same man who uploaded the photos of the site he called (erroneously?) ‘El Salto’, also visited a petroglyph site much further north in the Quebrada de La Chilca. He uploaded some photos of an (unrecorded?) petroglyph site; all posted in June 2010. The captions of the four photos that show the rock art all read ‘Loma de los petroglifos – Qda La Chilca – San Juan’ (Photo 1 – Photo 2 – Photo 3 – Photo 4). Having used either GPS or being informed by initiated people, the coordinates he provided (S. 29° 57′ 2.24″ and W. 68° 3′ 6.04″) indicated a spot about 4.6 km NNW of Bloque 52. Although I have not been allowed to visit the site, I think that this may be a new petroglyph site in the Quebrada de La Chilca. In order to avoid further confusion I have labelled this site La Chilca Norte. In the video a selection of images showing the variety of petroglyphs at La Chilca Norte has been included (Video only Figures 14A, B, C and D).

Figure 14. Possible location of the (new?) petroglyph site at La Chilca Norte. All locations of the rock art panels at this site (indicated by green squares) are approximated and most uncertain. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Figure 14. Possible location of the (new?) petroglyph site at La Chilca Norte. All locations of the rock art panels at this site (indicated by green squares) are approximated and most uncertain. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Video only Figure 14A. Petroglyph panel at La Chilca Norte. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photo by Thekingcrimson in Panoramio (2013).

Video only Figure 14B. Petroglyph panel at La Chilca Norte. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photo by Thekingcrimson in Panoramio (2013).

Video only Figure 14C. Petroglyph panel at La Chilca Norte. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photo by Thekingcrimson in Panoramio (2013).

Regarding the sites of La Chilca Norte and Quebrada de La Chilca I have some further comments. The photos of Quebrada de La Chilca were uploaded onto the internet in June 2010, only a few months after I was lied to about the existence of rock art in Ischigualasto and thus being disallowed to visit any rock art site in the park. How do the officials of the Visitor Centre at Ischigualasto explain that at least four people with private motorcycles visited an area in the park where tourists are not allowed to go to (at least I could not find any information at the Visitor Centre or in any web site about guided excursions to the Quebrada de la Chilca) only a few months after they refused me access?

There is more. As early as 2008 an (Argentinean?) family of four (?) clearly visited the ‘new’ petroglyph site of La Chilca Norte, apparently with private motorcycles. It seems that this party even camped (with a fire … in the Quebrada de La Chilca?). They speak of an excursion, although I do not know whether this was an official excursion organised by the Ischigualasto Visitor Centre. Pancho Pastor posted some photographs of this excursion on the internet. In one of those photos two people of this party appear in front of Bloque 58 – Panel A (Podestá et al. 2006: 183) in the Quebrada de La Chilca. The caption of another – more disturbing photograph – was: Esto es lo mas pintoresco de la excursión (al menos para mi ) y ademàs es una exclusividad de mi grupo ya que lo descubriò uno de los coroneles (Tom Murua) mientras el resto emparchaba una rueda de las Guanaqueros. En honor a èl lo he bautizado los Morrillos de Murua o los petroglifos de Tom’. If indeed they were accompanied by an official from the park at that occasion, then it is even the more alarming to see that a child in that photo is sitting right on top of one of the vulnerable petroglyph panels (Video only Figure 14D). It concerns the same panel a photo of which was posted onto the internet two years later by the other party with motorcycles. Was this family allowed to visit this site? If so, why? Were they supervised by an official guide at that occasion?

Video only Figure 14D. Petroglyph panel at La Chilca Norte. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photo by Pancho Pastor in Patagonia Off Road (2008).

∞

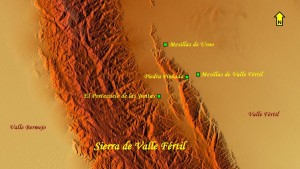

La Sierra de Valle Fértil

To the SE of the Visitor Centre at Ischigualasto is a rugged area, part of an extensive mountain range called Sierra de Valle Fértil, with at least eleven rock art sites (Figure 15). A fairly clear map of this area has been published by Anahí Ré, María Mercedes Podestá and Guadalupe Romero (Re et al. 2011: Fig. 2). On their map eleven sites appear: 1: Portezuelo de las Piedras Marcadas, 2: Puerta de las Quebradas, 3: Quebrada de Los Lagares, 4: Corral, 5: La Toma, 6: Los Rincones Norte, 7: Los Rincones Sur, 8: Piedras de Ontivero, 9: Puerta de la Quebrada de las Casas, 10: Quebrada de las Cacas Costado Norte and 11: Quebrada de las Vacas (2011: Table 1). No further location details are available in their paper.

Figure 15. Location map of the rock art complexes in the northern part of the Sierra de Valle Fértil and adjacent areas. All rock art locations (indicated by green squares) are approximated. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Figure 15. Location map of the rock art complexes in the northern part of the Sierra de Valle Fértil and adjacent areas. All rock art locations (indicated by green squares) are approximated. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

However, Ana Gabriela Guráieb, Diana Carro and Marcos Rambla (Guráieb et al. 2014) state that the petroglyph site of Puerta (de la) Quebrada de las Casas is located at S. 30° 16′ 17.3″ and O. 67° 44′ 37.1″, and the site of La Toma at S. 30° 13′ 49.37″ and O. 67° 46′ 82″ (O = Oeste = West). The latter location is incorrect as 82″ does not exist. Most likely the correct coordinates for La Toma in Google Earth are S. 30° 13′ 47.98″ and W. 67° 46′ 3.47″ (Figure 16). In the video a small selection of images showing the variety of petroglyphs in this part of the Sierra de Valle Fértil has been included (Video only Figures 16A, B, C, D, E and F). Further south in the Sierra de Valle Fértil are some more rock art sites that will be discussed more comprehensively later on.

Figure 16. Detailed location map of three rock art sites in the Sierra de Valle Fértil. All locations (indicated by green squares) are approximated. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Figure 16. Detailed location map of three rock art sites in the Sierra de Valle Fértil. All locations (indicated by green squares) are approximated. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Video only Figure 16A. Petroglyphs on Panel 2A at Los Rincones Sur, Sierra de Valle Fértil. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Re et al. (2009: Fig. 9).

Video only Figure 16B. Petroglyphs at Puerta de las Quebradas, Sierra de Valle Fértil. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Rolandi et al. (2006: Fig. 2).

Video only Figure 16C. Petroglyphs on Panel 8B at Puerta de las Quebradas, Sierra de Valle Fértil. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Re et al. (2011: Fig. 5a).

Video only Figure 16D. Petroglyphs on Panel 28A at Puerta de las Quebradas, Sierra de Valle Fértil. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Re et al. (2011: Fig. 5d).

Video only Figure 16E. Petroglyphs on Bloque 18 at Portezuelo de las Marcas, Sierra de Valle Fértil. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Re et al. (2006: Fig. 6).

Video only Figure 16F. Petroglyphs on Panel 9B at Portezuelo de las Marcas, Sierra de Valle Fértil. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Re et al. (2006: Fig. 7).

∞

El Chiflón

To the east of the Sierra de Valle Fértil is the Provincial Park El Chiflón (Figure 17 and Video only Figure 18). During an organised excursion through the northern part of the park (which encircles Cerro Tortuga), the guide informed me that also petroglyphs had been recorded in the park and at long last he showed me one of the locations, which proved to be only 100 m NW of the Visitors Centre and just north of the main road to Chile (RN-150). There are two sites with petroglyphs at this spot: Explanada Estación Guías (comprising at least two boulders with very faint petroglyphs) and Alero Explanada Estación Guías (a site comprising a small rock shelter). In the video a small selection of images (Video only Figures 18A) shows the variety of the very faint petroglyphs (at Explanada Estación Guías) and some other archaeological remains at El Chiflón.

Figure 17. Location map of the rock art sites at El Chiflón. All locations (indicated by green squares) are approximated. Yellow square indicates a site with ‘morteros’. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Figure 17. Location map of the rock art sites at El Chiflón. All locations (indicated by green squares) are approximated. Yellow square indicates a site with ‘morteros’. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Video only Figure 18. Detailed location map of the rock art sites at El Chiflón. All locations (indicated by green squares) are approximated. Yellow square indicates a site with ‘morteros’. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Video only Figures 18A. Collection of photographs of archaeological remains and rock art at El Chiflón. All photos Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Those two petroglyph sites are also described in a publication by Ana Gabriela Guráieb, Diane Susana Rolandi, Diana Carro and Marcos Rambla (Guráieb et al. 2010), who also mention the fact that – apparently after my visit in 2010 – a row of small houses (cabañas) was built very near the rock art. Indeed, this row of houses is clearly visible in Google Earth today. Such a development in a (sacred!) rock art site is completely unacceptable and should never have been allowed for (compare this with Twyfelfontein Lodge in Namibia, southern Africa). Finally, their publication also mentions the rock art sites of Base del Pucará El Chiflón (see Video only Figure 18), Loma de la Cañada and (Alero) Las Petacas (Falchi et al. 2012-2014: Fig. 6 – arriba), which is possibly the same site as Cerro Blanco and possibly Amaná as well. The name Loma de la Cañada is not indicated on their map (Guráieb et al. 2010: Fig. 1).

Remarkably, several of the locations of the sites at El Chiflón described in the publication by Guráieb et al. (2010) also appear in a video that was published in 2013 by Ana Gabriela Guráieb, Diane Susana Rolandi, Diana Carro, Marcos Rambla, Soledad Atencio and María Pía Falchi (Guráieb et al. 2013.). In this rather blurred video they also provide pretty indistinct photos of several rock art panels, and they also mention two rock art sites of which the locations are unknown to me as their names do not appear on any map that I have available: Alero Colgado (somewhere near Cerro Tortuga) and Peña del Niño (at Cerro Blanco). Their video will play an important role in this paper, as will be explained in the discussion further down.

∞

San Agustín de Valle Fértil

A good base to explore the attractions of San Juan and La Rioja is the pretty village of San Agustín de Valle Fértil. Pablo Cahiza (2007) describes the rock art sites in the neighbourhood of this village. He has marked seven rock art sites on his map (2007: Mapa 1) and also includes the coordinates of most of those sites (which have been reproduced in this paper). Four of the sites (Figure 19) will be discussed here, again in random order.

Figure 19. Location of four rock art sites near San Agustín de Valle Fértil. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth Relief Maps.

Figure 19. Location of four rock art sites near San Agustín de Valle Fértil. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth Relief Maps.

Only 1.8 km NNE of the centre of the Plaza San Agustín in the village is the rock art site of Mesillas de Valle Fértil (S. 30° 37′ 9.8″ and W. 67° 27′ 39.8″) with sixteen petroglyph boulders (Figure 20). There once may have been many more boulders, as Pablo Cahiza refers to earlier sources that mention the existence of more than 30 boulders. These ‘missing’ boulders may have been removed or even stolen. In front of the local museum (Museo Arqueológico – Centro Cultural Pachamalui) at San Agustín de Valle Fértil are some petroglyph boulders (Video only Figures 20A) that possibly come from Mesillas de Valle Fértil. I emailed the museum a few times to ask for additional information, but they never answered.

Figure 20. Location of three rock art sites near San Agustín de Valle Fértil. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Figure 20. Location of three rock art sites near San Agustín de Valle Fértil. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Video only Figures 20A. Collection of photographs of rock art in front of the local museum at San Agustín de Valle Fértil (Museo Arqueológico – Centro Cultural Pachamalui). All Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Pablo Cahiza (2007: Fig. 3) also reports one petroglyph boulder (Video only Figure 21) at El Portezuelo de las Juntas (S. 30° 40′ 44.7″ and W. 67° 33′ 7.8″); a site 9.4 km SW of the village square, and easily accessible just north of a dirt-road.

Video only Figure 21. Petroglyphs on a boulder at Portezuelo de las Juntas. Drawing Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Cahizo (2007: Fig. 3).

About 10 km NW of the Plaza de San Agustín is the rock art site of Mesillas de Usno (S. 30° 33′ 43.9″ and W. 67° 32′ 27″). At least four petroglyph boulders are located less than 200 m east of the main road (RP-510) and directly north of the village of Usno. The site has been described in the Diario de Cuyo, stating that there are dozens of petroglyph boulders and that this site was recently turned into a ritual centre for the descendants of the original Diaguita natives. Interestingly, the name Usno is said to have been derived from the quechua term ‘ushnu’, which means ‘lugar sagrado’, or ‘sacred place’. The fact that – all over the world – rock art sites almost invariably are ‘lugares sagrados”, is the central theme of my video.

The only site that I visited in this area is also the best known petroglyph panel of the region (Figure 22). This rock outcrop is called Piedra Pintada (again with only petroglyphs, though) and is found on an almost vertical cliff (at S. 30° 37′ 42.3″ and W. 67° 29′ 8.7″ in Google Earth), only 1.8 km WNW of San Agustín de Valle Fértil village centre. It is merely 25 meters NW of the dirt-road that leads out of the village. As this site (and other sites) are presented as a local tourist attraction it is clearly signposted (see Video only Figures 23). Therefore you cannot miss the petroglyph panel (Video only Figures 24), but fortunately the panel itself is very hard to reach, as it is located on a steep cliff about 15 meters above ground level (Photo).

Figure 22. Location of Piedra Pintada near San Agustín de Valle Fértil. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Figure 22. Location of Piedra Pintada near San Agustín de Valle Fértil. Map Copyright by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Video only Figures 23. Tourist signs indicating the location of the Piedra Pintada site very near San Agustín de Valle Fértil. All photos Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Video only Figures 24. Photographs of the Piedra Pintada site very near San Agustín de Valle Fértil. All photos Copyright by Maarten van Hoek.

Yet, the site is unsupervised and for that reason the ‘picnic’ place just below the cliff is often untidy and one can clearly see the signs of people attempting to climb the cliff. Also the indicator at the foot of the site proved to be damaged. Although Pablo Cahiza remarks that the state of preservation of Piedra Pintada is very good (2007: 254), I noticed some vandalism (graffiti) on the panel; testimonies of the violation of this ‘ushnu’. This act of violation at this unprotected tourist attraction at the edge of a tourist village brings me to discuss the four issues introduced at the introduction.

∞

.

PART II

Discriminatory Exclusivity Regarding Rock Art Research in Argentina

Having described a number of rock art sites in Cuyo, while primarily focussing on location and accessibility of those sites, I now will consider the issues introduced at the beginning of this paper. Most of my remarks in this paper are firmly based on non-falsifiable facts (although I cannot guarantee that the information published by Argentinean scholars is correct), together with my personal surveys and personal experiences in Argentina, and my personal opinions about certain matters.

∞

ISSUE 1

Have the locations of rock art sites in the Study Area correctly been published?

No, not in every case, and although every sincere scientist will agree that published information should be correct, mistakes are easily made. Incorrect or conflicting information can be the result of inaccurate observations and/or the uncritical use of information in earlier publications. Or one just makes understandable mistakes as, again, a mistake is rather easily made. Unfortunately, errors cannot always be corrected; sometimes only with difficulty. For instance, the observant spectator of my four La Rioja YouTube videos (2014) will have noticed that I misspelled the name of San Augustín (this should read Agustín) and that the location of El Chiflón is incorrectly marked on my introductory map. In fact it is located some 7 km to the ENE. In this paper and video all these errors have been corrected by me (and yet there may remain other errors).

Unfortunately there are many publications (whether scientific or not) that provide confusing and/or incorrect information. For instance, in the case of Kiosco (Ischigualasto), the location as stated by María Mercedes Podestá and Diana Susana Rolandi (2001: 66) is incorrect. Antonio Núñez Jiménez (1986) published several maps of petroglyph sites in Peru that are definitely incorrect (Van Hoek 2011a). Since 2008 Cristóbal Campana Delgado published and re-published an incorrect map of Alto de la Guitarra in northern Peru, even after having been personally informed by me in 2005 (and several times after 2005) about the incorrectness of that map (Van Hoek 2014).

The current paper, one previously published paper (Van Hoek 2011b) and five videos (see my Bibliography) reveal the location of many rock art sites in Cuyo of which I only visited eight rock art sites (El Toro, El Chiflón, Talampaya, Anchumbil, Parque Diaguita, Palancho, the Piedra Pintada at San Agustín de Valle Fértil and Banda Florida) and one geoglyph site (Vinchina). Therefore I know the exact locations of those eight sites.

The locations of all other sites mentioned in this paper were found by using information from books and papers I have at home and, most importantly, from publications downloaded from the internet. Most details about location of rock art sites were found in works, often posted on the internet, published by Argentinean academics. I emphasise again that I do not know the exact locations of those sites not visited by me. All location details of those rock art sites described here are based on the publications referred to in this paper. The location details (in the text and in maps) of all rock art sites that I did not visit – described in this paper and my video – may therefore be inaccurate or even incorrect. Should you not wish to publish possibly inaccurate or incorrect information, please contact the Argentinean scholars to ask for further details.

However, in this paper I also demonstrated that the locations of several rock art sites published by several respected Argentinean academics are often confusing, conflicting and sometimes incorrect. Their maps are often too vague or too large of scale. If this is done on purpose – in order to confuse the reader or to ban visitors – then those Argentinean academics severely underestimate the increasing amount of information that is available on the internet and thus the enormous power of the internet, especially of Google Earth. Moreover, if Argentinean academics claim to have the exclusive right to survey/excavate archaeological sites and publish information about those sites, do they also have the exclusive right to make mistakes?

Having said that, also captions should provide correct information. In this respect it is most surprising that several photos published in the official web site of the INAPL (Instituto Nacional de Antropología y Pensamiento Latinoamericano), Buenos Aires, Argentina, have a completely wrong caption. This organisation is the official institute that coordinates all (?) scientific rock art research in Argentina, which is – moreover – managed (at least in 2015) by Diana Susana Rolandi (la directora y investigadora del INAPL), one of the scholars who criticised me. For instance, the captions of several photos depicting rock art panels from Palancho and Sapagua incorrectly state that those panels are found at the site of Las Guachipas, Salta (hover the mouse over the thumbnails). This kind of incorrect information is scientifically unacceptable and carente de todo valor científico. When someone uses this incorrect information, the errors may easily be reproduced. Moreover, when someone would like to visit those sites and only would use those captions, she or he will be directed to the wrong spot. Well, Guachipas (or Las Juntas) (Photo 1 – Photo 2) is 475 km NNE of Palancho and 293 km SSE of Sapagua; so you better buckle up!

∞

ISSUE 2

Should Rock Art Sites be Accessible for All?

Of course not! Vandals and other disrespectful people should be always be repulsed! Moreover, many rock art sites are on private land and access must be granted before visiting a rock art site on private land, but I found that in most cases in the Andes local people take much pride in guiding you to ‘their’ rock art site. There are – of course – more instances where access is rightfully restricted, and in general I do not challenge that.

What I do passionately dispute however is the unjust difference that is often made between academic (or professional) archaeologists and non-academic people, not only regarding the right of access, but also regarding the right to publish information about a rock art site (see Issue 4), or even the right to attend a symposium about rock art. A good example of the latter issue is the discriminatory exclusion of non-academics at the XIX Congreso Nacional de Arqueología Chilena, held in Arica, Chile, in 2012. (Rupestreweb Groups): Sólo se aceptarán resúmenes de participantes que posean el grado de Licenciado en Antropología, mención Arquelogía o el Título Profesional de Arqueólogo.

What might be the reason to ban people from a rock art site? In their criticism personally towards me María Mercedes Podestá, Diana Susana Rolandi and María Pía Falchi accuse me of ‘intervenir en un sitio arqueológico’, which indeed sounds very negative. They seem to suggest that – especially in my case – there is question of disturbing (and vandalising?) of whatever archaeological evidence (compare this with similarly false allegations by Gori Tumi Echevarría López from APAR-Perú). In this respect I invite the interested reader to view the photos of large crowds on top of rock art sites (Photo), or people with vehicles near rock art sites (Photo) and people starting campfires at rock art sites (Photo). Those people, often locals, are truly disturbing archaeological sites and/or are giving a very bad example. Contrary, I assure the interested reader that my wife and I never did anything else than walking in Cuyo at sites that are either open to the public or for which we were granted permission to enter (most of the time accompanied by archaeologists, guides or locals). Moreover, after about 40 years of experience in the field, I know what not to do.

When visiting Talampaya in 2010, I was told that there were no excursions to Los Pizarrones or to other restricted petroglyph areas in the park, while in 2015 they confirmed by email that excursions did include visits to Los Pizarrones. Therefore I advise every visitor to Talampaya who is interested to see the impressive wall covered with petroglyphs (see Video only Figure 6A) to ask for a guided excursion to Los Pizarrones. However, when visiting Ischigualasto in 2010 the officials at the Visitor Centre lied to me regarding the existence of rock art in ‘their’ park. Thus I was disallowed to visit the rock art sites in the park, while it was definitely certain that several petroglyph sites were known at that time.

The existence of rock art at Ischigualasto is also evidenced by a short but interesting note in La Septima of April 2009 called: ‘Recrean en Ischigualasto la Ruta del Arriero’. In this article the director of INAPL, Diana Susana Rolandi, proposed to realise a special project involving the establishment of two touristic itineraries, specially laid out to visit three rock art sites in Ischigualasto: ‘El proyecto presentado antes mencionado prevé la diagramación de dos rutas o itinerarios turísticos, el primero por la ruta 150 hasta el paraje denominado [1]“Agua de las Marcas”, al cual se accede a pie desde la ruta, en media hora de caminata. El restante implica el traslado en vehículos con guías hacia [2] “Agua de la Peña”, para proseguir luego hasta [3] “Piedra Pintada”.

Apparently, those 2009-plans were never realised, as in 2010 the Visitor Centre at Ischigualasto obviously did not offer any rock art excursion. Moreover, in 2010 the officials of Ischigualasto repeatedly denied that there was rock art in the park. Well, there definitely is rock art in Ischigualasto, and I invite everyone to visit the park and to ask for a guided excursion to the petroglyph sites (any future visitor to Ischigualasto may refer to this article and my video).

Based on my experiences, I fear that the officials at Ischigualasto have been instructed (by whom?) to discourage and thus disallow visitors to visit the rock art sites in ‘their’ park by lying and denying and also by evasively ‘answering’ or even ignoring emails. In 2015 I emailed Ischigualasto(ppischigualasto@gmail.com; ischigualasto@hotmail.com.ar) and asked which excursion would include a visit to rock art sites. In their answer they recommended to take the ‘Circuito Clasico’ (I did that in 2010: rock art is not included in this excursion) and moreover they said that ‘los petroglifos se encuentran en nuestro museo’. Consequently I asked if those petroglyphs in their museum were replicas (they never answered this question), and explained that I would like to visit the rock art sites in the open air. In their very brusque, one-line answer they only suggested visiting Cerro Morado (which I visited in 2010). So I answered that ‘there is no rock art at Cerro Morado’ and repeated that I would like to visit the rock art sites in the north of the park and that I was willing to pay extra for that service. After that request they never had the courtesy to respond to my further emails. Also other Argentinean people completely ignored my emails regarding requests for extra information: INAPL (novedadesinapl@gmail.com), the Museo cultural Pachamalui in San Agustín de Valle Fértil, (jorgeluisvita@gmail.com) and La Septima (laseptima@sinectis.com.ar).

If indeed visitors are discouraged and thus disallowed to see rock art at Ischigualasto, then it is highly unacceptable and unethical to notice that Ischigualasto officials discriminate between ‘just visitors’ and professional, academic archaeologists (who – hopefully – are not being lied to). Or is it so that only Argentinean archaeologists are allowed to see, survey (and publish about) ‘their’ rock art (see Issue 4)? In this respect (or rather: disrespect), I am convinced that a respected rock art researcher like Robert Bednarik, who is – like me – a rock art researcher without being an academic archaeologist, will not be refused access. And if (hypothetically) the king of Holland, who married a woman from Argentina, would show up, and asked to be guided to the Piedra Pintada rock art site at Ischigualasto, I am convinced that the whole park would be immediately closed for a day, allowing him to see all rock art sites without any restriction.

∞

ISSUE 3

Should the Location of Rock Art Sites be Revealed or Not?

There are two general attitudes regarding the publication of the location of rock art sites. One can reveal the location of a site to whatever extent, or one can keep the location of a site completely under wraps. The latter possibility simply means: no maps, no coordinates, no photos, no explanatory text and even no names. But mind you, even when no maps or coordinates are provided, the location of a site can be traced when only the name and a photograph are published. This way I was able to exactly pinpoint the location of a rock art site in northern Peru only by using the photo and its caption, knowing that it was located somewhere in the Chicama drainage (Cruz Mostacero 2012: Fig. 6).

Not revealing any information about the location of a rock art site is (in my opinion) scientifically impossible and even scientifically inadequate, as the greater setting of a site is often decisive in the choice of the locale by the ancient manufacturers. The former possibility includes the use of names on all kind of maps (including – for instance Google Earth – satellite photos), coordinates, a textual description or even photos (Hurtadi Pedraza 2015: Imagen 4); preferably with a (correct) caption or text providing the name of the site. In my opinion it is completely up to the author(s) to decide to what extent the location of a rock art site is revealed.

When exposing the location in a publication, one can provide the general location on a large scale map without any details, so that uninitiated people will not be able to locate and visit the site. Alternatively, one can exactly disclose the location(s) in a map or a series of maps with many details and combined with other details so that the reader can easily locate and visit the site. A fine example is the thesis by Argentinean scientist Alvaro Rodrigo Martel who published in much detail the exact locations of many rock art sites and rock art panels around Antofagasta de la Sierra in Argentina (Martel: 2010: Capítulo 5). Whatever method will be used, the information must be correct.

Another accurate manner is to provide the UTM-coordinates or other geographical coordinates. Then it is – together with either GPS or Google Earth – very easy to locate the site. Yet, there sometimes is a discrepancy between the published coordinates and their factual locations in Google Earth. The coordinates may have been correctly published, for instance for the petroglyph site of Chillihuay in southern Peru (Van Hoek 2014), but several publications do give coordinates that do not match the location in Google Earth at all. For instance, Argentinean archaeologist Ana María Rocchietti (see my Simbal paper) provides the following co-ordinates for the Lúcumar petroglyph site in northern Peru: S. 7° 58′ 06″ and W. 78° 48′ 53″ (2012: 6). However, in Google Earth these data lead you to a spot no less than 800 m south of the factual location. When using the UTM co-ordinates of the location of the nearby Piedra del Sol provided by Peruvian archaeologist Daniel Seuart Castillo Benites in Google Earth (N. 0743897 and E. 9119195), one will reach a spot that is in reality 2000 m distant from the actual location (see my Simbal paper).

Such enormous discrepancies are scientifically unacceptable and should therefore not be published. However, errors like this can easily be avoided today by checking those data in Google Earth, preferably prior to publication. In this paper the locations of several ‘Argentinean’ petroglyph sites have been traced by using the coordinates published by several Argentinean archaeologists. As I have not visited those sites (except for a few) I cannot guarantee that their information is correct, and consequently is it uncertain that their locations on my maps are correct.

When visiting Cuyo in 2010, it sufficed to mention the name of Palancho (also known as Perfil del Inca) to find a taxi-driver in Chilecito willing to take me to that site, of which I initially found only the name on a very vague map in a publication by Argentinean archaeologist María Pía Falchi (2008: Fig. 1). It was my YouTube video about this rock art site of Palancho (published in 2014) that triggered three Argentinean archaeologists, María Mercedes Podestá, Diana Susana Rolandi and María Pía Falchi, to publicly attack not only my publication, but also my person. It was their unsubstantiated fear that especially my video would trigger ‘thousands’ of viewers to visit unprotected Palancho (los miles que accedan a su video vía internet puedan alcanzar este lugar desprotegido sin mayores dificultades). Please check for yourself how many people watched the Palancho video. For the record: Palancho is promoted as a tourist attraction in the (local) media. For the record: Palancho was already violated by locals (long?) before 2005! For the record: this paper contains many instances where Argentinean academics have revealed the exact location of (unprotected) rock art sites in Cuyo! For the record: Palancho can now easily be located using information from the internet (Photo 1 – Photo 2).

∞

Regarding the role of the local community it is interesting to read the article of Lorena López who interviewed Mercedes Podestá (López 2014: 41). Some of her answers will be repeated here and commented on by me. Additions by me have been placed between [ ].

The title of this interview is: “Hoy la arqueología va de la mano de la gente”; “Today archaeology is transferred to the hands of the people”. In my opinion that is – in general – exactly the problem with rock art protection: the people; rather their (positive or negative) mentality. I now will give the interested reader an example of a negative mentality. When I surveyed the unsupervised petroglyph site of Parque Diaguita, I first visited the museum in Campanas (Museo Acnin) to arrange for a permission to visit the site. Guided by a (female) employee of the museum, I drove with the taxi to the site, got out but after 5! minutes the official guide (and the taxi-driver) left me at the site without a word. The official never returned (fortunately the taxi driver did) and nobody kept an eye on me for at least five hours.

Much later, I found the following message on the internet regarding Parque Diaguita: Tomando la RP-11, a 6 km de Campanas y luego camino de ripio de 600 m. En zona llana, hay variedad de piedras con Petroglifos con motivos diferentes. La depredación de turistas inescrupulosos ha dañado el patrimonio del lugar. It proves that now the ‘turistas’ are blamed for the shameful depredation that indeed took place at Parque Diaguita. The author of this message conveniently ignores the fact that much earlier it was decided by Argentineans to construct the main road (now abandoned; the new road bypasses the site) cutting right through the sacred site. He or she also ignores that it is a fact that petroglyph stones have been stolen, also by local people living in Campanas, and I was shown one such stolen stone in the front garden of a resident of Campanas (see the last photo in my video about Parque Diaguita). Turistas do not usually steal blocks of stone hidden in their suitcases.

¿Cómo se encuentran los sitios? How does one find [new] rock art sites?

Mercedes Podestá: Our main partners are the people of the area. If it wasn’t for their help, it would often be impossible to locate a rock art site, because some areas are wooded and sometimes extremely thinly populated. Today archaeology is in the hand of the people; the attitude [of the academic world?] changed much in recent years. While our first priority work is still research, a very close second is the relationship with the local community because they are the true custodians of the rock art.

I fully agree with Mercedes Podestá about the most important, constructive role that the local communities (should have to) play. Indeed, the great majority of all rock art sites were already known to local people (which is understandable) long before interest in rock art started, last century. However, does Mercedes Podestá exclude people who visit the area, or foreigners who happen to discover/survey a rock art site in Argentina? Are tourists and foreigners not custodians of our world heritage? Are their discoveries and contributions not appreciated? Moreover, in her answer Mercedes Podestá completely ignores the destructive role of many locals and (local) authorities.

O sea que son valorados por las comunidades… Are they valued by the communities…?

Mercedes Podestá: At certain occasions we found graves – that were constructed very recently – or offerings next to sites with rock art; there is even a tremendous respect [?] for those sites.

This latter remark seems to be ‘wishful thinking’ to me (hence the [?]) and I indeed wished this was an absolute truth. It is namely a fact that most destruction of and vandalism to rock art sites in Latin America is caused by locals or even by national, regional and local authorities. For instance, it was shocking to see – in Google Earth – that an area immediately SW of the Estrellas Diaguitas geoglyph site near Vinchina in La Rioja was bulldozed some time after 2010 (see maps and photos in the introduction of my video). This should – in my opinion – never have been authorised. Not only the geoglyphs are ‘the site’ (unfortunately also the geoglyphs showed some damage in 2010), also the immediate surroundings are part of the sacred site and should be respected and protected.

¿Que le diría a un turista que va por primera vez? What would you tell a tourist who will visit [a rock art site] for the first time?

Mercedes Podestá: Enjoy and learn to appreciate the history that represents us as Argentines, although this sounds very clichéd. Our (pre)history began 12,000 years ago, but believe it or not, it is something which in general is unknown. So today we work in the diffusion of scientific knowledge and we noticed a great interest from the public.

Very strange (but acceptable) that Mercedes Podestá invites tourists to enjoy (and learn from) a rock art site, while simultaneously she excludes foreigners (in this case: me) to visit, enjoy and learn from a visit to a rock art site; not to speak about publishing about a rock art site (Issue 4). Furthermore, I claim that there is no ‘Argentinean’ rock art. Moreover, I am convinced that most Argentineans nowadays have no ancestral affiliation whatsoever with the ancient rock art in the Andes. Yet, Argentineans (and all ‘foreigners’ visiting Argentina) are responsible for the safeguarding of rock art sites in Argentina. It is moreover a great pity and a missed opportunity that in this interview Mercedes Podestá does not emphasise the fact that rock art sites are ‘ushnus’; sacred sites, and may be compared with graveyards, Roman Catholic churches, chapels and sanctuaries like the many Difunta Correa sites in Cuyo (see video).

∞

ISSUE 4

Do only academics have the right to publish information about rock art?

To reiterate, there is – in my opinion – no ‘Argentinean’ (or ‘Chilean’ or ‘Peruvian’ or … etc) rock art; only rock art that now happens to be located in the modern republics of Argentina and Chile and Peru (etc). Therefore, in this case I prefer to speak of Andean rock art. Modern political boundaries have nothing to do with prehistoric rock art distribution, and therefore rock art studies should – in my opinion – avoid any political involvement. On the other hand, rock art protection needs strong political regulation and thus national (see a very bad example), regional and especially local authorities are – or should be – responsible for the safeguard and management of ‘their’ ‘ushnus’; ‘their’ sacred (rock art) sites. However, in my opinion, that does not mean that only Argentineans have exclusive rights to visit/survey rock art in Argentina, or the exclusive right to publish information about ‘Argentinean’ rock art.

However, in 2014 Diane Susana Rolandi, María Pía Falchi and María Mercedes Podestá discriminatorily criticised me for having published the location of the rock art site of Palancho in western Argentina. But more importantly, they patronisingly and publicly pointed out that – according to Argentinean laws – only Argentinean archaeologists are allowed to visit/survey and publish information about Argentinean rock art sites. Foreigners should seek permission from the Argentinean authorities first.

While I fully agree that only academically trained archaeologists are allowed to scientifically excavate or to responsibly ‘disturb’ archaeological sites, I regard it completely unacceptable that it is not allowed for visitors (tourists and/or [non-academic] rock art researchers alike) to visit and then to photograph or videotape archaeological sites. For me, there is no difference between a rock art researcher who photographs or videotapes the famous Inca site of Machu Picchu in Peru (yes, there is rock art at Machu Picchu) or the remote rock art site at Palancho in Argentina. It is a fact that rock art sites are visited by locals and foreigners who take photographs and often publish their material on the internet. For the record: no-one ever told me that the site of Palancho is a restricted area (which it is not) and nowhere did I see a sign that indicated restricted access. For the record: on the contrary, Palancho and several other rock art sites in Cuyo are promoted as local tourist attractions (URL 1 – URL 2 – URL 3 – URL 4). For the record: before my visit in 2010 local Argentineans already severely vandalised several panels at Palancho. Needles to say that I did not.

Unfortunately, Diane Susana Rolandi, María Pía Falchi and María Mercedes Podestá, whom I truly regard to be sincere archaeologists, deeply committed to protect ‘their’ rock art, will never be able to stop vandals visiting and – sadly – violating rock art sites. Therefore, would it not be much better for them to educate people (especially the locals) to respect and protect the sacred rock art sites? Educating is what I modestly try to do in my videos, thus also in the Palancho video (and – for this occasion – more explicitly in the video that accompanies this paper).

I would also much appreciate if Diane Susana Rolandi, María Pía Falchi and María Mercedes Podestá (and several other academics) would value the contributions of non-academic archaeologists / rock art researchers and would professionally collaborate instead of unethically attacking caring people. Well, they did attack (only?) me (only?) because – in 2014 – I ‘revealed’ the location of Palancho in a YouTube video. Regrettably, María Mercedes Podestá, Diana Susana Rolandi and María Pía Falchi never personally wrote me in advance about these issues and moreover they did not realise (in advance) that ‘one catches more flies with honey than with vinegar’.

Most disturbing – in view of their pointless attack – is the fact that several of the locations of the sites at El Chiflón described in a publication of Ana Gabriela Guráieb, Diane Susana Rolandi, Diana Carro and Marcos Rambla (Guráieb et al. 2010) also appear in a Facebook video that was published – in 2013 – by Ana Gabriela Guráieb, Diane Susana Rolandi, Diana Carro, Marcos Rambla, Soledad Atencio and María Pía Falchi (Guráieb et al. 2013.).

Regarding this Chiflón-video I, above all, emphasise and condemn the authorship of Diane Susana Rolandi and María Pía Falchi, as those two Argentinean archaeologists accused me, together with María Mercedes Podestá, of inappropriately publishing – in 2014 – a video in which the location of the rock art site of Palancho was disclosed. In their attack they also demanded that I should remove that video about Palancho: “solicitamos el inmediato retiro del video sobre Palancho de YouTube“. Of course I did not do that.

Why I regard this demand as two-faced? Because (in 2013!) those two archaeologists co-published a video about rock art sites at El Chiflón, while their indications of the locations of the rock art sites at El Chiflón – moreover directly located along the main road (RN-150) – are far more accurate and revealing (despite the bad quality of their video) than mine of Palancho. It proved that the petroglyph rocks of Explanada Estación Guías are located only 100 m NNE of the main road, while the petroglyphs at Base del Pucará El Chiflón are only 650 m SSW of the same major tourist route. Everyone can easily walk to those sites without being supervised. Conversely, Palancho is located in a hidden spot about twenty kilometres north from the access from the nearest main road (RN-74). And yet, Palancho was already violated (by locals!) long before 2005 (Podestá et al. 2005: 72).

Mind you, I do not criticise Diane Susana Rolandi, María Pía Falchi and María Mercedes Podestá for revealing locations. I criticise them because they hypocritically criticised me for ‘revealing’ the location of Palancho in 2014, while – in 2013 – they did exactly the same (and even more accurately) in a video describing El Chiflón. I do not see any difference between their El Chiflón video and my video of Palancho regarding the anticipated and dreaded negative consequences. But now I have to correct myself. There are differences. I regard their blurred video more ‘harmful’ than mine because it offers much more detailed information about the location of unprotected rock art sites at El Chiflón, especially as they are located very near a major tourist route. They also claimed that my Palancho-video is “carente de todo valor científico” – “without any scientific value”. However, in my opinion their Chiflón-video is scientifically of very little value. The illustrations are too blurred and the text hardly legible to be of any scientific value. Only tourists and vandals might profit from the Chiflón-video.

So, they attacked me because my 2014-Palancho video is said by them to endanger the rock art of Palancho and to be scientifically of no value, while their 2013-El Chiflón video is not endangering the rock art at El Chiflón?? And their video is scientifically beneficial?? Or are those ‘differences’ explained by William Shakespeare: ‘to be academic, or not to be’. This indeed seems to be the bottom line.