Calling Card rock art sites, drawn by war parties in enemy territory to taunt their adversaries by illustrating deeds executed against them, are a newly identified site type on the northern Plains of North America. One such site is Cheval Bonnet, a small petroglyph in Northern Montana. Containing coup counting and horse raiding narratives from the early 1800s, analysis of these images shows that most of the petroglyphs can be identified as Crow drawings, even though they are carved in the heart of Historic Blackfeet tribal territory. Once this site was identified as a calling card petroglyph, I was able to identify three others elsewhere on the northern Plains (PDF available).

Calling Card rock art sites, drawn by war parties in enemy territory to taunt their adversaries by illustrating deeds executed against them, are a newly identified site type on the northern Plains of North America. One such site is Cheval Bonnet, a small petroglyph in Northern Montana. Containing coup counting and horse raiding narratives from the early 1800s, analysis of these images shows that most of the petroglyphs can be identified as Crow drawings, even though they are carved in the heart of Historic Blackfeet tribal territory. Once this site was identified as a calling card petroglyph, I was able to identify three others elsewhere on the northern Plains (PDF available).

by James D. KEYSER

Calling Cards:

a New Plains Rock Art Site Type

Keywords: North American Plains, Rock Art, Crow Indians, Plains Warfare

open full-res PDF (2,3 MB)

Plains Indian Biographic tradition art shows combat and coup count narratives (including horse raids), drawn and painted by Plains Indian artists living from Canada to northern Mexico (Keyser 2004). One little-known biographic art expression was the “calling card” site, painted or carved deep inside enemy territory to taunt your foes by recording your own war honors in their “back yard.” Such sites—painted on trees near enemy camps—are known from historic records, but only recently have these been recognized archaeologically by a pattern of Montana rock art sites. The Cheval Bonnet site, located in northern Montana, led me to recognize this site type and identify three other calling card rock art sites in the region.

Figure 1. Cheval Bonnet site location at base of streamside cliff on Cut Bank Creek. figure in center points to panels 1 and 2, panel 3 is further to the left behind green bush.

The Cheval Bonnet Site

Cheval Bonnet is a small petroglyph scratched on a streamside sandstone cliff (Figure 1) at the only ford across Cut Bank creek for more than 30 km upstream from the large Blackfoot[1] winter camp at Willow Rounds. Located on the warpath from Crow country that runs northwest to the Blackfeet (Figure 2) and then east to the Assiniboine homeland (Denig 2000: Plate 77), this stream crossing would have been known to local Indians and raiders from other tribes who invaded the area to steal Blackfoot horses.

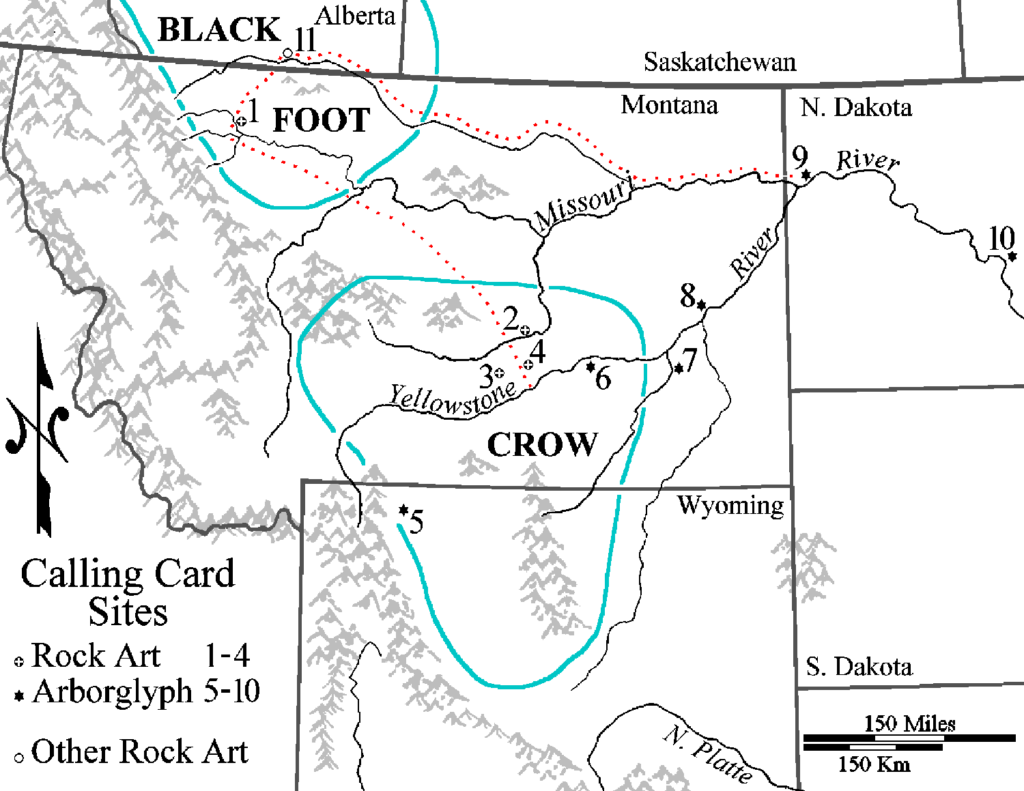

Figure 2. Northern Plains area showing locations of Writing-On-Stone, Blackfoot and Crow tribal territories, and Historic war trail between them and Assiniboine territory (red dotted line). Numbered sites are calling card rock art and arborglyph sites:1, Cheval Bonnet; 2, Horned Headgear; 3, 30-Mile Mesa; 4, Turner Rockshelter; 5, arborglyph site 48PA401; 6, Bierce arborglyph; 7, Pumpkin Creek arborglyphs; 8, Hosmer arborglyph; 9, Little Muddy Creek arborglyphs (Taylor 1895:123); 10, Painted Woods; 11, Writing-On-Stone.

The Rock Art Imagery

Cheval Bonnet petroglyphs are Historic period biographic narratives scratched on three small panels on a sandstone cliff on the north side of Cut Bank creek. Such narratives are the most common rock art in this part of the northwestern Plains, due to more than 100 sites at Writing-On-Stone on the Milk River in southern Alberta only 80 km northeast in the heart of the Historic Blackfoot homeland (Keyser 1977; Klassen 1998). At Writing-On-Stone, biographic narratives illustrating horses and warriors account for more than 75 percent of the rock art, and most of those images are in a Blackfoot style drawn by artists from all four tribes of the Blackfoot confederacy (Keyser 1977; Keyser, Poetschat 2012; Keyser et al. 2014). What distinguishes Cheval Bonnet is that five of its seven images are executed in an artistic style unmistakably related to the Crow tribe.

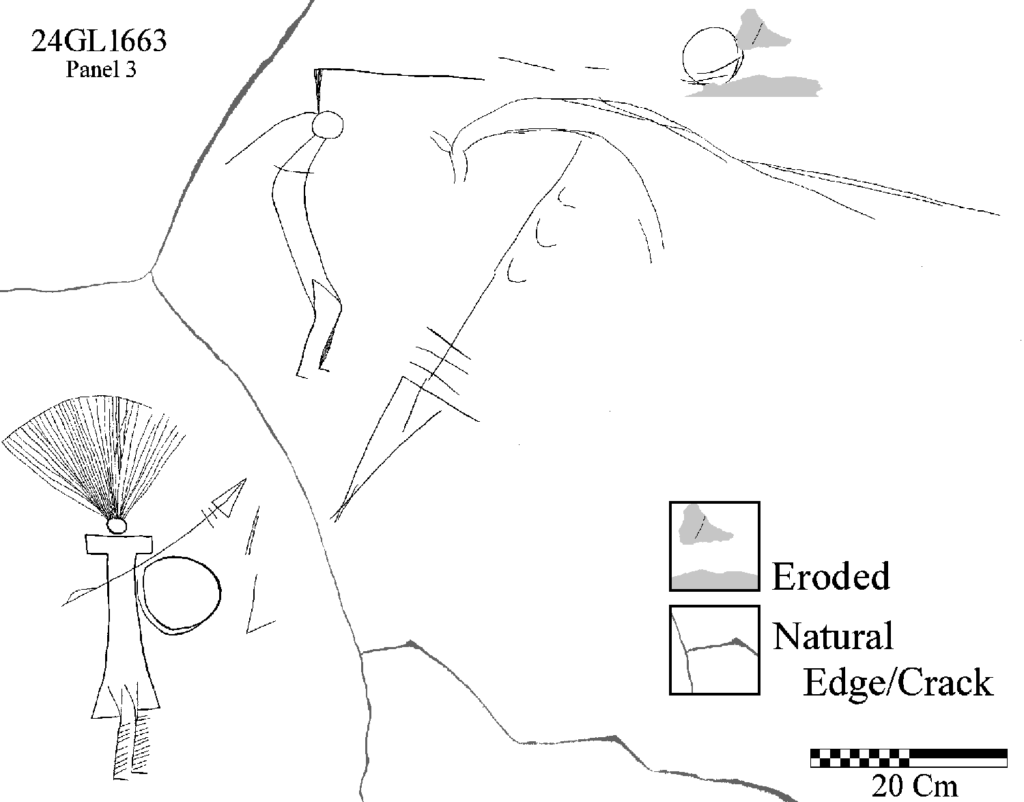

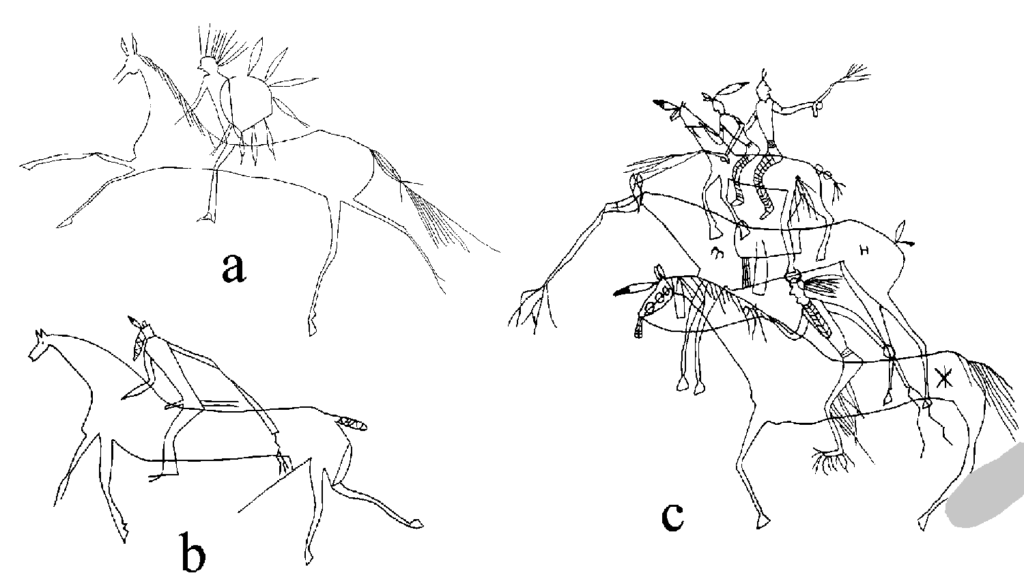

Figure 3. Panel 3 at Cheval Bonnet shows two coups counted by the rider of the horse drawn at the upper right.

Cheval Bonnet petroglyphs are typical biographic images showing humans holding weapons and wearing clothing and headdresses; horses and their accouterments; and human footprints and horse tracks. Four humans are illustrated at the site. Two, drawn completely in a coup count scene (Figure 3), are pedestrian foes of the scene’s inferred protagonist—a third human who can be identified only by the presence of his shield and tracks. Both complete humans in this scene are tall with bent knees that create a posture indicating movement and narrative action.

One man wears a long scalplock—a single braid dangling down his back—while the other wears a stand-up, eagle-feather war bonnet. This man also wears a long, A-line coat with rectangular sleeves, and fringed leggings indicated by a short fringe along the right side[2] of both legs below the coat’s hem. This warrior carries a lance diagonally across his body and a circular shield below the coat’s right sleeve. The small shield diameter, the metal projectile points on his and his opponent’s lances, and his opponent’s horse indicate that this is an Historic period drawing (Keyser 2010).

The scene’s protagonist is inferred from a small-diameter shield positioned just above the horse in the upper right quadrant of this composition. Starting behind this shield and extending across it to the left are five dashes representing human footprints leading to the handle of a tomahawk with a triangular metal blade that strikes the bent-forward human atop his head. The shield and foot tracks are an example of a commonly used pars pro toto synecdoche standing for the warrior-artist/protagonist in this scene.

The single human on panel 2 is a V-neck figure with a bent-body posture standing next to a horse (Figure 4). This human is part of a Blackfoot coup count scene drawn by an artist different than that who drew the other coup counts.

Offensive weapons include lances and a tomahawk; defensive weapons are two buffalo hide shields. Lances tipped with outsized metal points—indicated by cross pieces illustrated on the shaft—are used in combat by both the inferred protagonist and the well-dressed warrior. The protagonist’s lance extends downward under the horse’s neck, pointing directly at the pedestrian. Running alongside its upper shaft are a three C-shaped hoofprints indicating the path of the protagonist’s horse as he rode up to count coup on the pedestrian. This is a typical biographic art illustration showing striking coup with a lance. The tomahawk, floating just above the vanquished foe, is clearly recognizable as a coup-strike weapon.

Figure 5. This coup count tally painted on the Schoch war shirt (collected in 1837) shows three enemy warriors wearing Chief’s coats. Robe now in the Bernisches Historisches Museum, Berne Switzerland (photograph by the author).

The Chief’s coat is a cheaply made, elaborately decorated, Euro-American-manufactured copy of a military-style dress uniform. These were traded to Indians during the 1700s and 1800s by fur-trading companies to secure the patronage of tribal leaders (Chronister 1996). Such Chief’s Coats are illustrated in robe art in this same manner (Figure 5), showing the warrior’s upper legs and thighs visible in front of the garment’s hem to indicate coat tails extending down and behind the upper legs.

Four horses are drawn at Cheval Bonnet. The combat scene horse is a shorthand animal, illustrated with only as much detail as necessary to tell the story. Thus, only its back, front quarters, and high-arching neck with small head are shown. Another horse is a simple mature style animal, drawn in a Blackfoot style.

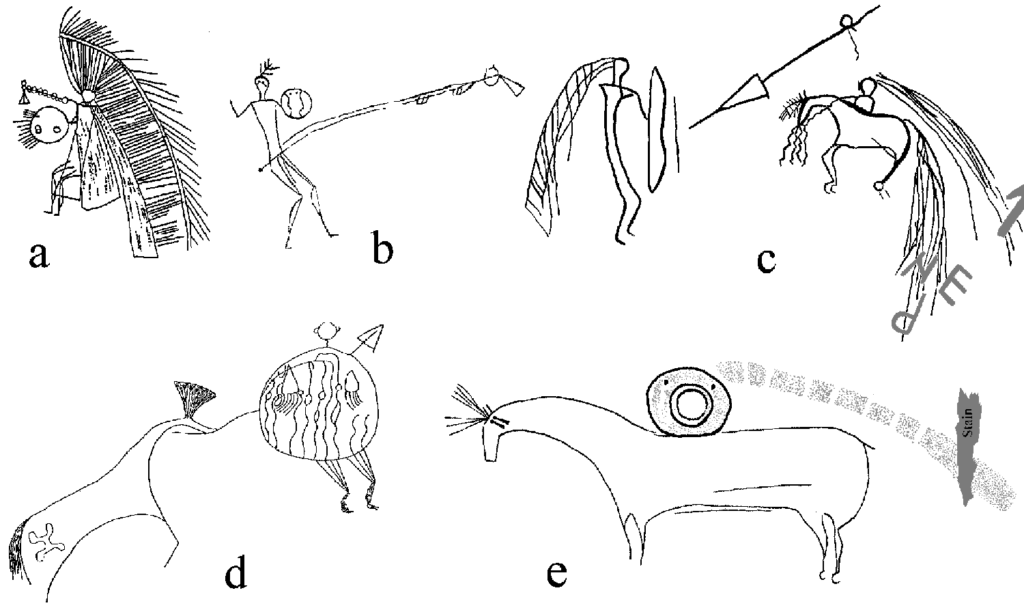

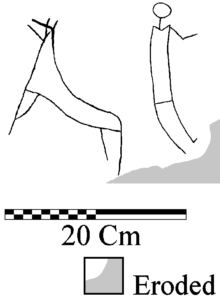

Two panel 1 horses each wear a feather bonnet (Figure 6). Both are drawn with a fluid style distinguishing them from the other horses and suggesting they are the product of a third artist. Projecting from atop each animal’s head is a tall, triangular, fan of lines representing a feathered bonnet. Smaller curved lines extending upward from the bonnet’s top represent decorative fluffs of eagle-down or horsehair attached to the tip of each eagle feather.

Feather horse bonnets are rare in Plains rock art; with only ten examples so far identified, all in the Musselshell and Yellowstone river drainages in Crow tribal territory (Keyser 2012). The Cheval Bonnet horse bonnets are among the most elaborate yet noted, and in specific detail, they compare favorably to one illustrated by frontier artist George Catlin (Taylor 2001:61) who saw it worn by the horse of a prominent Crow chief in 1832.

The Coup Count Composition

The ten elements on panel 3 are skillfully composed into a vivid narrative recounting two coups by the panel’s author. Using the biographic art lexicon (Keyser 1987) this scene is easily read and understood. Initially, we see the artist, who must be inferred from his horse, his tracks, and his weapons, counting his first coup by dismounting and running up to an enemy to strike a fatal blow with a tomahawk. Five dashes are his tracks indicating his path running into the engagement.

The artist also recorded a second coup, counted against a well-armed pedestrian opponent whose high status is indicated by his war bonnet, Chief’s coat, and fringed leggings. In this action, C-shaped horse tracks indicate the protagonist rode his horse by the enemy to strike coup. The pedestrian carries his lance at “port arms,” apparently using it and his shield to fend off the blow. In the absence of an illustrated wound, this suggests that the action portrayed was only the striking of this enemy with the lance rather than a fatal attack with a killing blow.

Stylistic Analysis

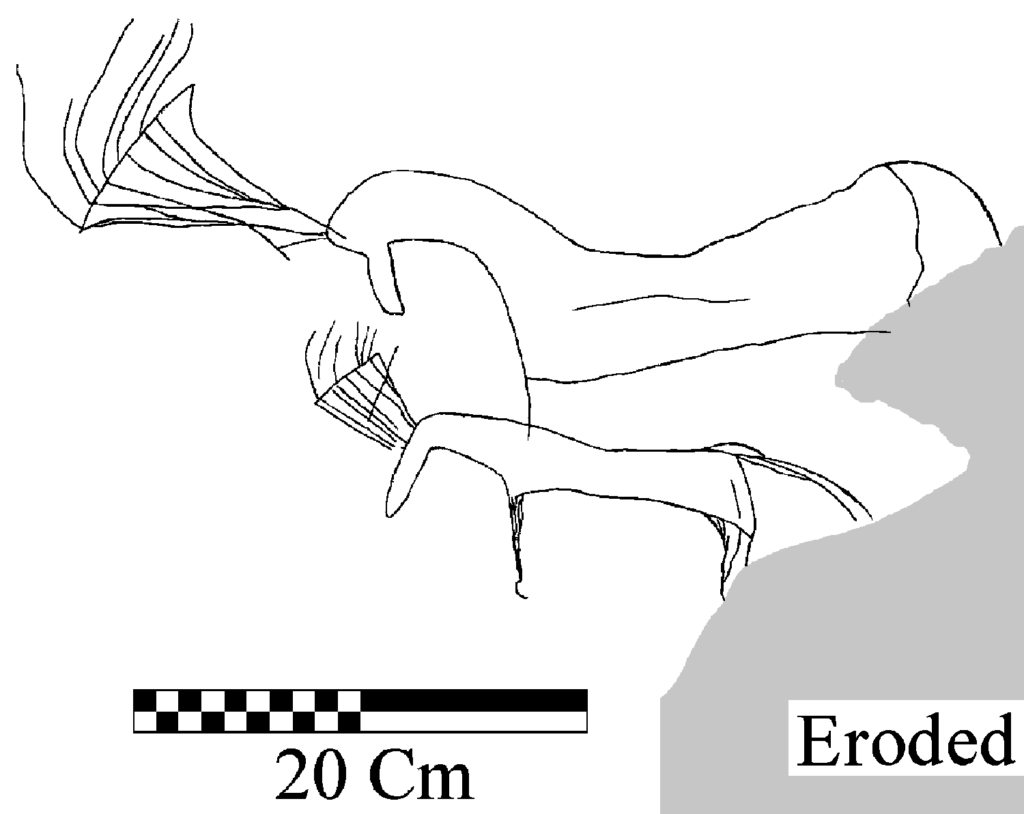

Three Cheval Bonnet motifs—high arched horses’ necks, tall fluidly posed humans, and feather horse bonnets—indicate Crow authorship of most site images. Plains rock art horses with long, highly arched necks and downward pointing heads are characteristic of “Crow style” rock art (Keyser, Renfro 2016), found almost exclusively in the Crow homeland of south-central Montana and northern Wyoming (Figure 2). Typically, such horses (Figure 7c-e) are associated with a complex of other attributes (including horse bonnets and tall linear humans) that have been identified as characteristic Crow imagery by comparison with Historic period painted bison robes (Brownstone 2001; Keyser 2012).

Figure 7. Crow indicators illustrated in rock art at sites in traditional Crow territory include tall, fluidly posed humans with modeled thighs and calves (a- d); horses with high, arched necks (c-e); and horses wearing feather bonnets (d, e).

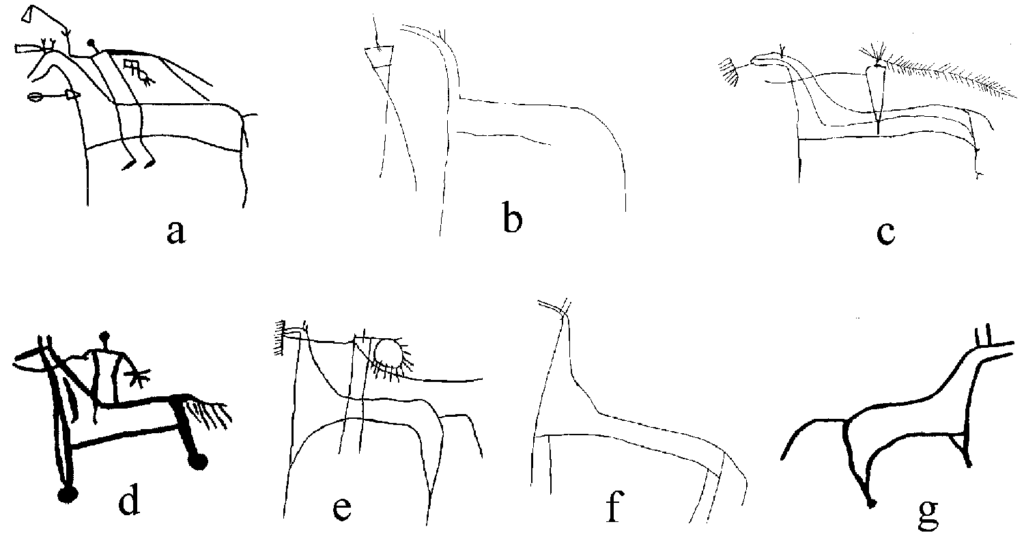

In contrast to these Crow style horses, Blackfoot artists drew horses (Figure 8) as mature style animals with much straighter and more upright necks and heads facing forward (Keyser, Renfro 2016). Blackfoot mature style horses wear entirely different accoutrements and only have small rectangular body, V-neck, hourglass-body, or triangular-body style human figures as riders or foes (Keyser 1977; Klassen 1998).

Figure 8. Blackfoot style horses show a different shape than Crow horses. They are also associated with rectangular, V-neck, or hourglass-body style humans.

Tall humans with fluid posture show essentially the same distribution as Crow style horses. These contrast markedly to the simpler, more static figures characteristic of similar-age Blackfoot biographic drawings (Figure 8a-e). Horse bonnets even more strongly indicate Crow authorship. All such bonnets in rock art, other than those at Cheval Bonnet, are found in “Crow country” in the Yellowstone and Musselshell river drainages of south-central Montana.

In contrast to the Crow style motifs on panels 1 and 3, the panel 2 horse and V-neck style human are typical Late Biographic style Blackfoot motifs, like hundreds drawn at Writing-On-Stone. Formal analysis confirms that this is a Blackfoot style horse (<Keyser, Renfro 2016); a fact consistent with the Cheval Bonnet location in the heart of Blackfeet tribal territory.

Chronology

Metal projectile points, a metal tomahawk, horses, small shields, and a Chief’s Coat date Cheval Bonnet to the Historic period. Although metal lance points first appeared on the Northern Plains in the early 1600s (Keyser, Kaiser 2010:124-128), the occurrence of two such points, and the metal-bladed tomahawk, suggest that this scene represents combat after AD 1750, when such weapons had become commonplace. Likewise, Late Biographic style horses on all three panels date to the fully equestrian period of Plains history from AD 1770 to 1880 (Keyser 1987:48-50; Keyser, Klassen 2001:19). But the Crow style horses and humans can be more precisely dated. These almost certainly date sometime before the mid-1860s, after which time Crow artists drew in a more realistic style (Figure 9) and, in fact, they are very similar to drawings on Crow bison robes dated between AD 1830 and 1860 (Brownstone 2001). The height of popularity for the Chief’s Coat was also within this probable 1820-1860 timespan.

Figure 9. Crow horses drawn after approximately AD 1860. a, Musselshell site (24ML1049); b, c, Joliet site, Montana.

Interpretation

Cheval Bonnet petroglyphs are biographic images drawn to boast about a man’s war record in a form that others—both friend and foe—would easily understand (Denig 2000:18-19). The explicitly narrative coup count scenes are readily recognizable, and evidence from Historic sources indicates that the stand-alone horses on panel 1 are simple, shorthand narratives—horses stolen from enemies—whose stories are implied rather than explicit (Keyser et al. 2013). The Crow artist drew these horses wearing a feather bonnet to show they were now “Crow” animals.

But why carve these petroglyphs here? The Blackfoot horse is easily understood. Carved in the heart of Historic Piegan (Blackfeet) territory, that tribe’s warriors were the most accomplished northwestern Plains horse raiders (Ewers 1958), and a lone man returning from an expedition against any of several enemy tribes might well have stopped at this familiar stream crossing to leave a record of his success—considered one of the bravest deeds a Blackfoot warrior could accomplish.

But the reason for the Crow petroglyphs, so far outside their traditional territory, is also clear. We know that raiders often left images near enemy camps to boast of their prowess. These drawings, which functioned as calling cards to announce the artists’ presence in enemy territory, are most frequently recorded in historic documents as charcoal-drawn “arborglyphs” sketched on the whitened trunks of large dead trees. Ethnohistoric sources record at least 10 examples of such arborglyphs on dead, whitened cottonwood snags and stumps near enemy camps and villages (Bierce 1866; Bourke 1962:268; Grinnell 1971:31-34; Hyde 1968:54; James 1823:I:296-297; King 1964; Pond 1986; Taylor 1895; Welch 1924), and one such drawing was actually associated with a war lodge (Hosmer 1962). There is also an archaeologically recorded arborglyph drawn with charcoal (Conner, Johnson 2012).

Edwin James, writing about Omaha Indians in present-day Nebraska described these calling card arborglyphs in considerable detail:

“[war parties] peel off a portion of the bark from a tree and on the trunk . . . delineate hieroglyphics, with vermillion or charcoal, indicative of the success or misfortune of the party, in their proceedings against the enemy. These hieroglyphics are rudely drawn, but are sufficient. . . to convey the requisite intelligence. . . .combatants are generally represented by small straight lines, each surmounted by a head. . .and are readily distinguishable from each other; the arms and legs are also represented, when necessary to record the performance of some particular act, or to exhibit a wound. Wounds are indicated by the representation of. . .blood from the [injured] part; and . . . a line for the arrow. . . .killed are represented by prostrate lines. . .wounded or killed [riders]. . .spout blood, or . . .fall from their horses. Prisoners are denoted by their being led, and the number of captured horses is made known by the number of . . . their track[s]. . . .guns taken, [are indicated] by bent lines, on the angle of which is [illustrated]. . .the [flint]lock. Women are portrayed with short petticoats, and prominent breasts, and unmarried females by the short [braids] at the ears.” (James 1823: I:296-297)

Ethnohistoric sources confirm such arborglyphs were drawn to brag of one’s own prowess and to taunt enemies who found them. Discussing Painted Woods in North Dakota, Welch (1924) notes “Whenever a war party. . .would pass that way, they would paint their war deeds upon the boles of certain dead trees as a taunt to their enemies.” Others (e.g., Taylor 1895) said that opposing war parties passing by such imagery “retaliated in kind” by adding their own paintings to already decorated trees “in a spirit of bravado.” We have one surviving sketch of such images, drawn in 1866 (Figure 10). It shows a tree stump in the Yellowstone valley painted with rifles shooting bullets at horses and wagons, humans, and even a boat (Bierce 1866). Bierce’s drawing appears to be quite accurate, since it mimics biographic art drawn at many rock art sites and in early ledgers of the same period (Keyser 2000).

Therefore, if war parties who were sneaking through enemy territory drew their exploits on trees, it also seems likely that they would have drawn similar imagery as rock art—especially since all tribes had a well-developed tradition of recording a man’s coups at rock art sites (Keyser 2004: 67; Keyser, Klassen 2001:243). This is almost certainly the situation at Cheval Bonnet, where easily identifiable Crow drawings are scratched in the heart of Blackfoot territory. Both local warriors and other raiders would have noted these drawings and understood their meaning.

Three other Montana rock art sites contain calling card imagery. Turner Rockshelter (Keyser 2007) is a hidden redoubt deep in Crow country on a well-documented war trail. Here, small groups of Blackfoot warriors bivouacking for a short period sometime between 1880 and 1895 while waiting for horse raiding opportunities at nearby Crow camps, drew their war deeds to taunt Crow rivals and flout their military prowess and courage in entering enemy territory.

Two other calling card rock art sites are also located in Crow country, both dating considerably earlier than Turner Rockshelter. One is Horned Headgear (24ML508), located at a well-known Musselshell River crossing (Loendorf 2012). There, the primary composition shows an Assiniboine warrior participating in a horse raid against Crow enemies. The artist of this composition took great care to identify himself and his enemies, down to specifics of their clothing and their horse’s equipment and accoutrements, allowing Loendorf to date the site to between AD 1780 and 1825. Equally importantly, the artist identifies himself and his opponent with sufficient detail that any contemporary tribesman—friend or foe—would have known who the participants were and could have understood the outcome of the fight. By carving at this well-used trail access into the Musselshell valley, outside his own Assiniboine tribal territory but well within Crow territory, the Assiniboine artist left a calling card that taunted the defeated Crows with the fact that he had come among them to steal their horse and defeat one of their best, while living to tell about it and fight another day.

The third calling card site is Thirty Mile Mesa (24ML402), where petroglyphs associated with cribbed-log war lodges show horses and a boat carrying four humans (Mulloy 1965). These petroglyphs are identified as Blackfoot based on the hourglass body human figures (Conner 1984: 129; Keyser 2007) and the Blackfoot style horses depicted there and good evidence dates this images to 1806 (Cramer 1974). The site location, on a high overlook with a south-facing view into the Yellowstone valley, would have been a perfect Blackfoot stopping place, and leaving a calling card petroglyph there would have been essentially the same behavior as documented for arborglyphs made only a few decades later (Hosmer 1962; King 1964; Taylor 1895; Welch 1924).

Conclusion

Cheval Bonnet petroglyphs are a Crow war party’s rock art calling card, left deep in Blackfeet country. Three site motifs are exclusively linked to Historic Crow biographic rock art in Crow territory and the styles of humans and horses on panels 1 and 3 are duplicated almost exactly in Historic Crow robe art (Brownstone 2001; Keyser, Renfro 2016). Furthermore, these diagnostic images are not drawn in Blackfoot biographic art—either rock art or painted robes.

The site is one of four such calling cards confirmed on the Montana Plains, but others certainly exist. Recognizing them in the future, in Montana and surrounding areas, will become much easier as archaeologists understand this site type and learn how they are identified.

James D. KEYSER

Oregon Archaeological Society

jkeyserfs@comcast.net

[1] Blackfoot refers collectively to the three tribes of the Blackfoot confederacy, while the name Blackfeet refers specifically to the local tribe, now residing in Montana, and in whose traditional territory the Cheval Bonnet site is located.

[2] Throughout the document, right and left are described from the perspective of the viewer.

References Cited

Bierce A.G. 1866. Route Maps of Journey from Fort Laramie, Dakota Territory to Fort Benton, Montana Territory 1866. Manuscript on file at Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT

Bourke J.G. 1962. On the Border with Crook. Rio Grande Press, Chicago, IL

Brownstone A. 2001. Seven War-Exploit Paintings: A Search for Their Origins. in Studies in American Indian Art: A Memorial Tribute to Norman Feder, pp. 69-85, edited by Christian F. Feest, European Review of Native American Studies, University of Washington Press, Seattle, WA.

Chronister A. 1996. Chiefs Coats Supplied by the American Fur Company. Museum of the Fur Trade Quarterly 32(2):1-7

Conner S.W. 1984. The Petroglyphs of Ellison’s Rock (24RB1019). Archaeology In Montana 25(2-3):123-145.

Conner S.W., Johnson A. 2012. Indian Art on Standing Trees. Archaeology In Montana 53(2):19-24.

Cramer J.L. 1974. Drifting Down the Yellowstone River with Captain William Clark, 1806: A Pictographic Record of the Lewis and Clark Return Expedition. Archaeology In Montana 15(1):11-21.

Denig E.T. 2000. The Assiniboine. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman. Previously published as Indian Tribes of the Upper Missouri. Forty-Sixth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1930, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Ewers J.C. 1958. The Blackfeet: Raiders on the Northwestern Plains. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman

Grinnell G.B. 1971. By Cheyenne Campfires. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln

Hosmer J.A. 1962. A Trip to the States in 1865. Frontier Omnibus. Sources of Northwest History No. 17 Montana State University and Montana Historical Society, Missoula

Hyde G.E. 1968. Life of George Bent Written from His Letters. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman

James E. (Compiler) 1823. Account of an Expedition from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains Performed in the years 1819 and ’20, by Order of the Hon. J.C. Calhoun, Sec’y of War: Under the Command of Major Stephen H. Long. From the Notes of Major Long, Mr. T. Say, and other Gentlemen of the Exploring Party. Two Volumes. H. C. Garey and I. Lea, Philadelphia

Keyser J.D. 1977. Writing-On-Stone: Rock Art on the Northwestern Plains. Canadian Journal of Archaeology 1:15-80.

Keyser J.D. 1987. A Lexicon for Historic Plains Indian Rock Art: Increasing Interpretive Potential. Plains Anthropologist 32:43-71.

Keyser J.D. 2000. The Five Crows Ledger: Biographic Warrior Art of the Flathead Indians. University of Utah Press.

Keyser J.D. 2004. Art of the Warriors: Rock Art of the American Plains. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Keyser J.D. 2007. Turner Rockshelter: A Blackfeet Redoubt in the Heart of Crow Country. Plains Anthropologist 52:9-27

Keyser J.D. 2010. Size Really Does Matter: Dating Plains Rock Art Shields. American Indian Rock Art 36:85-102

Keyser J.D. 2012. Northern Plains Horse Bonnets: “His Horse Wore a Magnificent Headdress”. Whispering Wind 40(5):4-10.

Keyser J.D., Poetschat G. 2012. “On the Ninth Day We Took Their Horses:” Blackfeet Horse Raiding Scenes at Writing-On-Stone. American Indian Rock Art 38.

Keyser J.D., Kaiser D.A. 2010. Getting the Point: Metal Weapons in Plains Rock Art. Plains Anthropologist 55:111-132.

Keyser J.D., Kaiser D.A., Brink J.W. 2014. Red is the Color of Blood: Polychrome Paintings at DgOw-20. Canadian Journal of Archaeology 38:27-75.

Keyser J.D., Livio A. Dobrez L.A.C., Hann D, Kaiser D.A. 2013. How is a Picture a Narrative? Interpreting Different Types of Rock Art. American Indian Rock Art 39:82-99

Keyser J.D., Klassen M.A. 2001. Plains Indian Rock Art. University of Washington Press, Seattle.

Keyser J.D., Renfro S. L. 2016. A Horse is a Horse—and They Can Tell Us Things. American Indian Rock Art In Press.

King C. 1964. Campaigning with Crook. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Klassen M.A. 1998 . Icon and Narrative in Transition: Contact-period rock-art at Writing-On-Stone, Southern Alberta, Canada. In The Archaeology of Rock-Art, Christopher Chippindale and Paul S. C. Tacon, editors, pp. 42-72. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Loendorf L. 2012. The Horned Headgear Site, Montana. American Indian Rock Art 39:71-80

Mulloy W.T. 1965 The Indian Village at Thirty Mile Mesa, Montana. University of Wyoming Publications 31(1).

Pond S.W. 1986. The Dakota or Sioux in Minnesota as They Were in 1834. Minnesota Historical Society Press, St. Paul.

Taylor C. 2001. Native American Weapons. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman

Taylor J.H. 1895 Sketches of Frontier and Indian Life. Privately Published by the Author, Washburn North Dakota.

Welch A.B. 1924. War Drums (Genuine War Stories from the Sioux, Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara), <http://www.welchdakotapapers.com/2013/10/war-drums-genuine-war-stories-from-the-sioux-mandan-hidatsa-and-arikara-written-by-col-a-b-welch-a/>.

Leave a Reply