TRACCE no. 10 – by Séverine Marchi

In this short notice, we will consider rock art of the most characteristic sites of the western African area, located south of the Sahara, between Senegal and Nigeria.

Unlike the Saharan rock art which has been well studied by lots of researchers, the sub-Saharan one is much less known. The first mention of it has been published in 1907 by Louis Desplagnes, after his survey of the central plateau of Niger. Afterwards, Raymond Mauny, in 1954, reali zed a important catalogue of the rock art sites in western Africa. In spite of some recent works conducted in different regions and particularly in Mali (Huysecom 1990), the researches are again scarce.

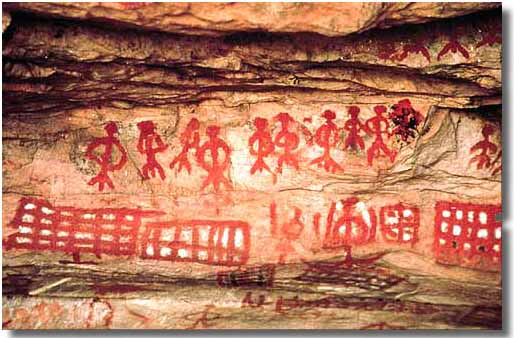

Anthropomorhic and geometric figures, Modjodjé, Mali (Pays Dogon) (Photo MAESAO)

We will divide the main subjects of this sub-Saharan rock art in three principal groups:

- the representations which seems to be related to neolithic facies

- the figures which can be compared to Saharan themes

- the schematic paintings in relation with traditional rites.

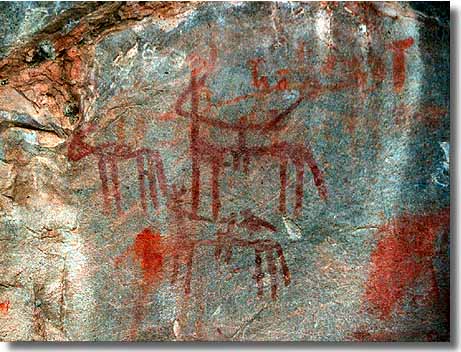

Horses mounted by weaponed personages. Airé Soroba, Mali (photo MAESAO)

Rock art connected with neolithic rock shelters

In the National park of the Baoule’, situated in south-eastern Mali, some rock shelters, like Fanfannyégènné I and II, present a phase of dotted engravings. These eroded figures representing bovine’s heads, radiating circles or snakes are overlaid by schematic paintings. In the relative chronology established for the area, they constitute one of the most ancient period and are probably connected to a neolithic facies dated, in Fanfannyégènné I, to the end of the second or the beginning of the first millennium B. C.

In Nigeria, the rock shelters around Birnin Kudu offer some naturalistic paintings. They represent animals, like cows, antelopes or goats and could be also related to a neolithic occupation.

Actually, these types of figures, differing in style, seem to illustrate the oldest phases of rock art in the sub-Saharan region.

Figures of Saharan style

In West Africa, Saharan rock art and its chronology are relatively well known. It is very interesting to note that some sites located to the south are characterised by representations very similar. The figures can he painted as well as engraved. They illustrate dromedaries, carts, hunting scenes with horses and inscriptions (Tifinagh and Arab).

Chronologically, it is possible to compare them to the figures of the two last subdivisions of Saharan art, the periods of Horse and Camel.

The theme of hunting, current in the “Adrar des Iforas”, appears at Aìré Soroba, a site recently discovered in the Inland Delta of the Niger, in Mali (Marchi 1997). In this rock-shelter, hunting scenes are characterised by horses with geometrical or linear body. Animals are mounted by personages wearing a head-dress of ostrich feathers. They are armed and chase away ostriches, giraffes or antelopes. These figures corresponding to the oldest groups recognised in the site can be situated approximately in the first millennium A. D. Otherwise, the same theme is represented in two other sites in Niger (Kourki) and in Burkina Faso (Aribinda).

We can also attribute to the first millennium A. D. the three paintings of dromedaries discovered in Airé Soroba. They are actually the most southern representations known in western Africa, even when this pattern is current in Sahara.

The cart’s representations are also very scarce in the sub-Saharan Africa and we just know actually two engraved examples in Tondia (Mali). This site marks also the southern limit for the extension of this kind of figure. In the same way, the inscriptions in Arab or tifinagh characters (transcription of the Tuareg language) are not very numerous in the region and they are generally situated along the river Niger.

The site of Airé Soroba provides interesting data about the Arab inscriptions which constitute one of the last phases in the relative sequence of paintings. A short sentence, in which a date is mentioned, record a pilgrimage to Mecca in the 11th century A. D. It confirms the presence of Islamic populations in the Inland delta of the Niger during this period.

Schematic representation of ships. Airé Soroba, Mali (photo MAESAO)

Schematic representations related to traditional rites

These representations are essentially paintings executed on the occasion of ritual ceremonies like circumcision, initiation or wedding. Abstract signs, anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures in red, white or black, are principally illustrated in the rock shelters of the Dogon area, in the “Point G” cave in Bamako (Mali) and also in the Marghi region (Nigeria).

Their chronology is not really established, but they could be relatively recent and we know, by the oral tradition, that some of them have been revived during the last decades. Subjects like humans mounting horses are sometimes illustrated and it could be possible to see a persistence of ancient themes.

Ostrich hunting scene, red painting. Airé Soroba, Mali (tracing MAESAO)

We can add to these groups some particular figures which seem to be unique in the region: an engraving of fish discovered in Bamako-Sotuba, near the river Niger and the group of painting ships from Airé Soroba. At present, such representations of boats are only known in Upper Egypt (Winkler 1938).

If we consider the whole sites known actually in western Africa, we note that they are concentrated in the Sahelian and Sudanese savannahs. That can be the result of insufficient researches in the others climatic zones, more difficult to prospect because of the forested environment.

The sites with Saharan style figures are, as for them, located in the Sahelian savannah and they could mark a limit of the extension of northern populations to the south. This rock art offers a large corpus of figures, sometimes unique in the area. Its complete study could maybe provide some others data concerning the origin and the movements of populations in the sub-Saharan Africa.

Séverine Marchi

6, rue Racine

F- 69100 Villeurbanne

MAESAO:

Mission Archéologique

et Ethno-arquéologique Suisse

en Afrique de l’Ouest

Bibliography

- BOURLARD (A.). 1989. Projet d’étude de “l’abri-sous-roche du Point G” à Bamako (République du Mali). Bruxelles: Université Libre de Bruxelles. Mémoire de licence en histoire de l’art et archéologie (not published).

- DESPLAGNES (A. M. L). 1907. Le platean central nigérien, une mission archéologique et ethnographique au Soudan français. Paris: E. Larose.

- HUYSECOM (E.). 1990. Fanfannyégèné I: un abri-sous-roche à occupation néolithique au Mali : la fouille, le matériel archéologique, l’art rupestre. Wiesbaden : F. Steiner. (Sonderschriften des Frobenius-Inst. ; 8).

- HUYSECOM (E.), MARCHI (5.) 1997. Western African Rock Art, in VOGEL (J. O.). The Encyclopedia of Precolonial Africa : Archaeology, History, Languages, Culture, and Environments. Walnut creek: Altamira Press Editors, 352-357.

- HUYSECOM (E.), MAYOR (A.), MARCHI (5.), CONSCIENCE (A.-C.). 1996. Styles et chronologie dans l’art rupestre de la Boucle da Baoulé (Mali) . L’abri de Fanfannyégènné II, Sahara, 8, 53-61.

- MARCHI (5.) 1997. Etude des peintures rupestres d’Airé Soroba (République da Mali), in Forum des Jeunes Africanistes. Bern: Société Suisse d’Etudes Africaines (to be published).

- MAUNY (R.). 1954. Gravures, peintures et inscriptions rupestres de l’Ouest africain. Initiations africaines (IFAN), XI. Dakar.

- SHAW (Th.). 1978. Nigeria. Its archaeology and early history, Ancient Peoples and Places, 88. London.

- WINKLER (H. A.). 1938. Rock-drawings of Southern Upper Egypt I, Archaeological Survey in Egypt. London: Oxford University Press.

- ZELTNER de (Fr.). 1911. Les grottes à peintures du Soudan français. L’Anthropologie, 22, 1-12.

back to index TRACCE no.

![]()

![]()

Leave a Reply