Since the beginning the achievement of a correct chronological attribution has represented an important point of any rock art research. But since the beginning any chronological attribution has been subjected to the risk of being questioned, not accepted or simply updated. So rock art dating is often controversial…

by Andrea Arcà

TRACCE PHP-Nuke version, 2002-2011 |

Dating and (up)dating Valcamonica rock art

chronological experiences in Valcamonica Rock Art

presented at the 2001 Intensive Course on European Prehistoric Art, Tomar (Portugal)

1 – Cronology: a solution or a problem?

Since the beginning the achievement of a correct chronological attribution has represented an important point of any rock art research. But since the beginning any chronological attribution has been subjected to the risk of being questioned, not accepted or simply updated. Only recently the direct dating experience has obtained some “scientifically” tested results, mainly when applied to the paintings, where it is possible to date organic material. So rock art dating is often controversial: some one wants to pre-date the art, some one other prefers to post-date it.

On of the best “post-dating” examples is the La Grotte de Altamira, mea culpa d’un sceptique, written by the French scholar Cartailhac, who finally accepted the Palaeolithic attribution of the Altamira cave paintings. A “pre-dating” example is given by the cup-marks in the Alps: they have been often supposed to be neolithic, while on the contrary the archaeological evidence starts in the late Bronze Age.

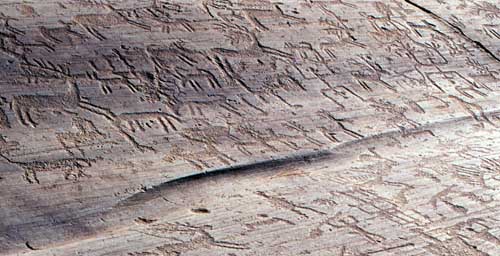

Figure 1. The Cro da Lairi cup-marked slab (Photo: A. Arcà); detailed record in EuroPreArt (choose Italy - western Alps)

This chronological incertitude is probably the most important reason why the official archaeology is often so sceptic regarding rock art research. Contrarily to other countries, in Italy, for example, thus where we have one of the most important European open-air engraved area, there is no university course specifically devoted to rock art studying, nor any officially funded exhaustive recording project.

Rock art is very useful for the front-cover images of various archaeological books, congresses, exhibitions, but, apart this interesting feature, there is not a deep contact between the archaeological academic world and the rock art research teams. The chronological hazard plays a great role in this separation.

Figure 2. Front-covers of two archaeological congresses (left UISSP 1996, right PAESE 1997) proceedings

2 – Valcamonica, number is strength

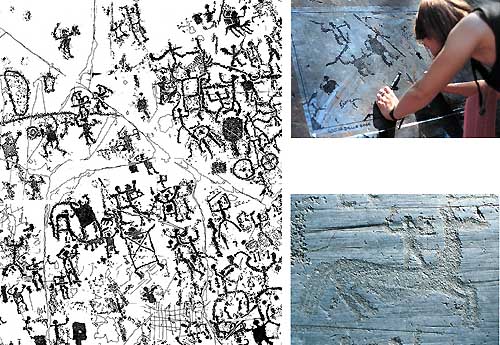

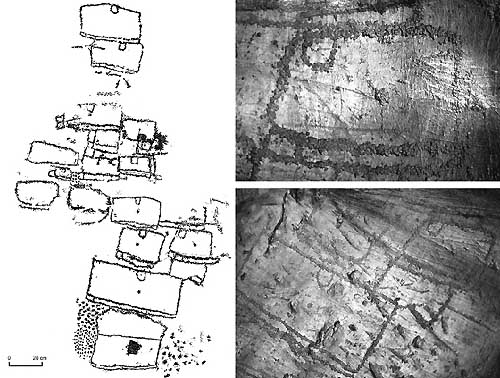

Despite such a problematic approach, some situations are particularly favourable to find some chronological keys archaeologically based. One is the Valcamonica (the Valley -Val- of the Camunnian people -Camonica-). It is situated in Lombardy, Italy, central Alps. It has been estimated that hundreds of thousands (never officially totally counted) of figures have been engraved over the rocks of Valcamonica. Only one of the last discovered rocks, the great rock of Paspardo, named also “the Rock of the Roses”, discovered in the 1997 by Footsteps of Man, bears more than 650 figures.

Figure 3. Tracing of the great rock of Paspardo (left and right - up) and Iron Age rider on Naquane rock n. 50 (right down, tracing Footsteps of Man, photo A. Arcà)

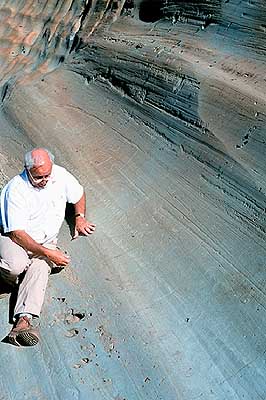

Why so many engraved figures? Here in Valcamonica we have a particular kind of rock, the permian sandstone. It is a siliceous fine granulated sandstone, heavily polished by the glacier during the last glacial era: it looks like and it acts as a real natural blackboard. Only one other valley in the Alps shows similar condition, thus the rock there is called pelite: it is, not casually at all, the M. Bego.

Figure 4. Prof. Henry De Lumley on a Mt. Bego engraved rock: the sandstone is very similar to the Valcamonica one (photo A. Arcà)

Such a quantity of figures, such a crowding of signs represents by itself a huge statistical opportunity: if many occurrences are repeated, they are not casual. In this sense dating Valcamonica rock art could open the door for dating many other rock art areas in the Alps, and not only.

3 – Valcamonica, the Anati’s periodisation

Valcamonica rock art has been officially discovered in 1914, being the Cemmo boulders cited in a Touring Club guide. Since this time many scholars studied the engraved rocks. Not all of them focussed on chronology. But generally there was the conviction that Valcamonica rock art was in general an Iron Age Rock Art.

Figure 5. Copper Age daggers and schematich human figures on the Cemmo 2 boulder (photo A. Arcà)

In 1955 was instituted the National Park of the Engraved Rocks of Naquane. Naquane it’s a local popular site name, deriving from Aquane, who are the legendary water fairies. The park, which contains 104 engraved rocks, has been instituted by the Lombardy Archaeological Superintendency.

Figure 6. The entrance of the National Park of the Engraved Rocks of Naquane, Capo di Ponte, Valcamonica (photo A. Arcà)

In 1957 E. Anati arrives in Valcamonica. He founds in 1964 the Camunnian Center of Prehistoric Studies. Its first years of research are particularly important, with the complete study (tracing and recording) of the Luine Park. The greatest intuition of ANATI is represented by the enlargement of the chronological frame, i.e. the understanding that many engraving phases covered as different layers the camunian rocks. Not only Iron Age, but also Neolithic, Copper Age, Bronze Age, and a few Epi-Palaeolithic figures. The evidence of more ancient periods was given by representation of archaeologically dated objects, mainly metal weapons.

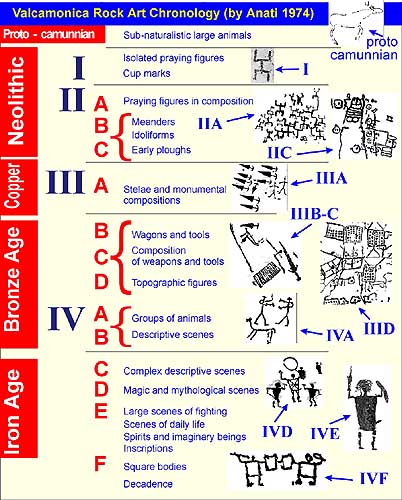

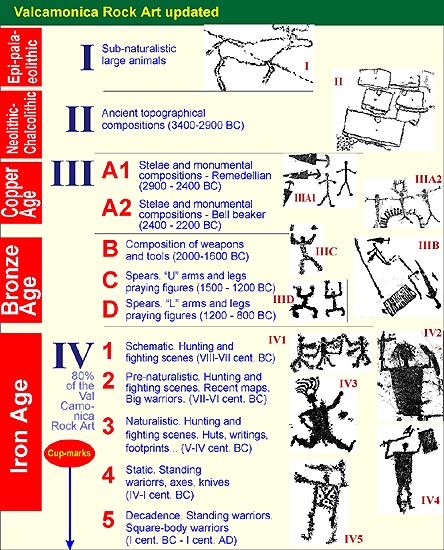

Anati proposed a chronological table, divided in 4 styles identified by roman numbers. Mainly (ANATI E, 1976, Evolution and Style):

- STYLE I – Neolithic – oranti (praying figures)

- STYLE II – Neolithic – oranti – dogs – maps – idoliforms

- STYLE III Copper Age (statuae stelae, monumental compositions, daggers – axes – halberds, deer – dogs – cows – wolves) and Ancient – Middle Bronze Age (daggers – axes)

- STYLE IV Late Bronze Age (schematic anthropomorphs) and Iron Age (the 80% of Valcamonica rock art, standing warriors, duels, riders, hunting scenes, huts, etruscan inscriptions, footprints…)

Figure 7. Valcamonica chronology by Anati

Some styles have been subdivided in sub-phases, e.g. IIIA – B – C – D (Bronze Age).

It is to be noticed that the very first chronological subdivision proposed by Anati was much more simple: I Neolithic, II Copeer Age, III Bronze Age, IV Iron Age.

4 – Valcamonica Chronology updated

Research in Valcamonica rock art is going on: during the last years some problems emerged in the Anati’s periodisation. Many rocks have been retraced, particularly the entire Copper Age phases, in order to get a better accuracy in the recognition of figures and of superimpositions.

4a – Topographic compositions

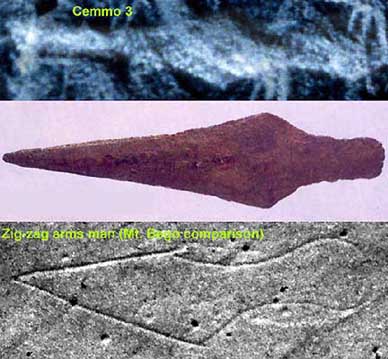

Topographic compositions, or maps, are constituted by regularly repeated geometric modules.

They are the only figures which are covered by the Copper Age figures (Borno 1, Bagnolo 1, Ossimo 8). Basing on the study of the superimpositions, the maps represent the most ancient phase (apart the Epi-palaeolithic style) of the Valcamonica rock art (a similar consideration should be reflected in the Mt. Bego rock art). Some compositions which have been interpreted by Anati as idols (Sellero, Paspardo) and assigned to the Style II, are more likely to be interpreted as maps. They constitute the phase II of the Valcamonica rock art chronology (see point 4c).

Figure 8. Topographic composition at Vite, Paspardo, late Neolithic - first Copper Age (photo A. Arcà)

Figure 9. Topographic composition overlapped by Copper Age (Remedello 2 phase 2800-2400 BC) daggers and ploughing scenes (tracing A. Fossati - P. Frontini)

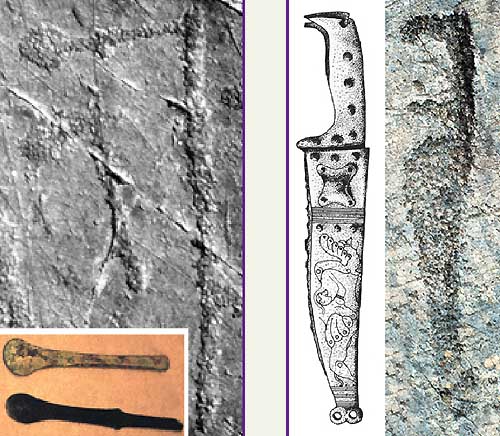

4b – Copper Age

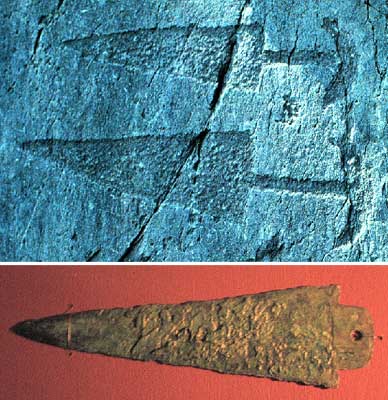

Introducing a more precise comparison with the archaeological finds, mainly metal blades, the Copper Age and Ancient Bronze Age phases have been better specified. Regarding this point is fundamental the work of R. C. DE MARINIS and of his co-researchers (A. FOSSATI, S. CASINI ) exposed in the catalogue of the “Pietre degli Dei” (the Boulders of the Gods – 1995) and in the NAB review.

The IIIA style (Copper Age) has been divided into three sub-phases:

- IIIA1 (remedellian Copper Age 2900-2400 BC)

- IIIA2 (bell-beaker Copper Age 2400-2200 BC),

- IIIA3 (Ancient Bronze Age)

Figure 10. Archaeological comparison: Remedellian kind daggers (Remedello 2, 2800-2400 BC, engraved (Cemmo 2) and real one (photo A. Arcà)

Figure 11. Archaeological comparison: Ciempozuelos (Bell-beaker) kind daggers (2400-2200 BC), engraved (up Valcamonica, down Mt. Bego) and a real one

This subdivision, based upon the recognition of different kinds of metal weapons, encloses also human and animal figures, which are clearly associated to these representations.

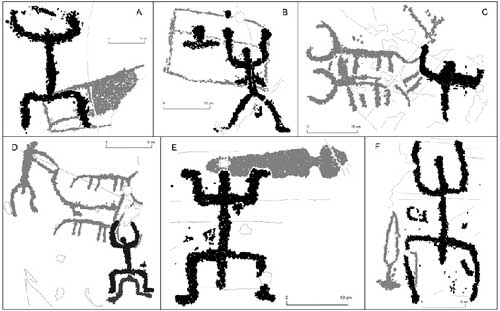

4c – Praying figures and the Middle – Late Bronze Age

One of the main problems in the Anati’s chronology is represented by the Style I – II. The key-figure, like a fossil guide, of these styles is the so called “orante” (praying figure), dated by Anati to the Neolithic by comparison with the Neolithic pottery. The fact is that in Valcamonica no “praying figures” is covered by Copper Age or later figures. On the contrary in various cases praying figures cover Copper Ages, Bronze Age (in 1 case also Iron Age) figures.

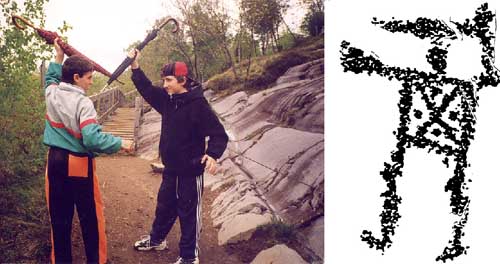

Figure 12. Praying figures superimposed to Neolithic maps, Copper Age ploughs, Bronze Age daggers at Foppe di Nadro Park (photo A. Arcà)

Many praying figures are weaponed, so clearly belonging to the last phases of the Bronze Age.

The chronology of the praying figures has been revised, with the contribution of. R. C. DE MARINIS (1994), A. FOSSATI (1992), C. FERRARIO (1990), A. ARCA’ (2001).

Figure 13. Weaponed and dressed praying figure on a Vite rock (photo A. Arcà)

Many scholars are now convinced that the great part of the praying figures must be shifted to the middle-final Bronze Age, with some isolated figures reaching the first Iron Age (XV-VIII cent. BC). The author is strongly convinced that no Valcamonica praying figure should be attributed to the Neolithic (ARCA’ 2001).

4d – Iron Age

Another point of discussion is the passage from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age. In this case the key is represented by the riding practice: as in the northern Italy the first archaeological evidence (Golasecca graves) belongs to the first Iron Age and not to the Late Bronze Age the style IV, which was related also to the Late Bronze Age in the Anati chronology, is now ENTIRELY belonging to the Iron Age, starting from the VIII cent. BC and not from the X cent. BC. The Style IV, Iron Age, has been also subdivided in 5 sub-phases, numbered with arab numbers, starting from the VIII cent. BC (style IV1) and reaching the roman period (style IV5). This work of definition has been particularly conducted by A. FOSSATI.

The consequence of all those considerations is this chronological table:

Figure 14. Valcamonica chronology updated (Copper Age by De Marinis, Iron Age by De Marinis and Fossati, modified in phase I and II by Arcà 2001)

5 – Valcamonica rock art: an archaeo-stylistic chronology

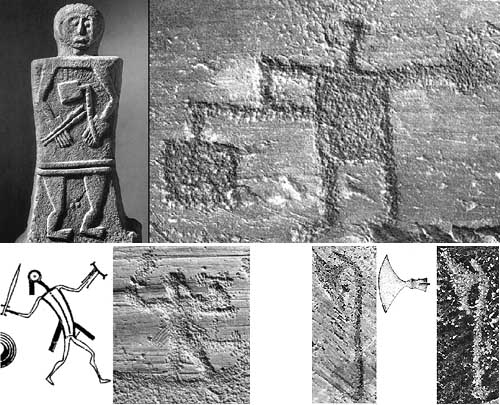

- A detailed chronological evidence is given by comparison with archaeological finds (axes, spears, swords, shields, knives), by the utilisation of the Etruscan alphabet, by the presence of subjects and themes typical of the Iron Age art, e.g. in the situlae art.

- A second focus point is given by the study of the overlappings. Many figures have been executed one over the other. The permian sandstone preserves very well any engraved sign. So it is often possible, looking carefully at the “theft” of the pecking, to understand the sequence of the engraving practice.

Figure 15. Archaeological comparisons: left, engraved Ancient Bronze Age axes (Foppe di Nadro) and the real spatula axes. Right, the Benvenuti kind knife (VI sec BC, from Este) and a figure from the rock 4 of Paspardo in Valle (IV2 style)

Figure 16. Archaeological comparisons: up the Filetto stele (VII-VI sec BC) and a figure from the rock 14 of Naquane (quadrangular axe, IV2 style). Down left an embossed figure on the Hochdorf kline (2nd half VI sec BC) and an acrobatic rider from the rock 50 of Naquane (IV3 style). Down right engraved half-moon shaped axes (Late Iron Age, style IV4-5) and the hellebardeanxte of Sanzeno (III cent. BC)

In this way the chronology of Valcamonica rock art is now strictly tied to an archaeological evidence, mainly thanks to the large chronological extension of weapon figures (from Copper Age to Iron Age) and to the great number of figures and related superimpositions, which assures a statistical validity. In conclusion the same idea of a “stylistic” dating must be revised and up-dated: it should more properly be defined as an archaeo-stylistic dating, i.e. a rock art periodisation which clearly matches the corresponding archaeological periods.

Andrea Arcà

Footsteps of Man – coop. archeologica Le Orme dell’Uomo

p.zza Donatori di Sangue 1

25040 CERVENO (BS)

EuroPreArt webmaster

www.europreart.net

A part of Naquane rock1

See you in Valcamonica...

Bibliography

AA. VV.

1994 Le pietre degli dei – menhir e stele dell’età del Rame in Valcamonica e Valtellina, (a cura di S. CASINI), Bergamo. ANATI E.

1966 Il masso di Borno, Breno.

1976 Evoluzione e stile nell’arte rupestre camuna, Edizioni del Centro, Capo di Ponte.

1979 I Camuni, alle radici della civiltà europea, Milano.

1982 Luine collina Sacra, Capo di Ponte.

ARCÀ A.

1992 La roccia 13 di Vite Paspardo, elementi per un archivio di archeologia rupestre, “Appunti”, 19, Breno, pp. 25-31.

1993 Vite, incisioni topografiche: prima fase dell’arte rupestre camuna, “Notizie Archeologiche Bergomensi”, 2, Bergamo, pp. 91-98.

1996 Chronology and interpretation of the “praying figures” in Valcamonica rock art, preatti del 2° Congresso Internazionale di Archeologia Rupestre, “TRACCE On line Rock Art Bulletin”, 9

1997 Settlements in topographic engravings of Copper Age in Valcamonica and Mt. Bego rock art, in Proceedings of the XIII International Congress of Prehistoric and Protohistoric Sciences – Forlì 1996, 4, Forlì, pp. 9-16.

1999 Fields and settlements in topographic engravings of the Copper Age in Valcamonica and Mt. Bego Rock Art, in Prehistoric alpine environment, society and economy, papers of the international colloquim PAESE ’97 in Zurich, edited by Philippe Della Casa, Bonn, pp. 71-79.

2001 Chronology and interpretation of the “praying figures” , in Archeologia e Arte Rupestre, l’Europa, le Alpi, la Valcamonica, atti del 2° Congresso Internazionale di Archeologia Rupestre, Milano, pp.185-198

ARCÀ A. – FERRARIO C. – FOSSATI A. – RUGGIERO M. G.

1996 Paspardo, loc. ‘al de Plaha, in Le vie della pietra verde, l’industria litica levigata nella preistoria dell’Italia settentrionale, Torino, pp. 256-258.

ARCÀ A. – FOSSATI A. – MARCHI E. – TOGNONI E.

1995 Rupe Magna, la roccia incisa più grande delle Alpi, Ministero dei Beni Culturali e Ambientali, Soprintendenza Archeologica della Lombardi, Consorzio per il Parco delle Incisioni Rupestri di Grosio, Sondrio

1999 Le ultime ricerche della Cooperativa Archeologica Le Orme dell’Uomo sull’arte rupestre delle Alpi, atti del 2° Congresso Internazionale di archeologia rupestre, Milano, pp. 139-166

BATTAGLIA R.

1934 Ricerche etnografiche sui petroglifi della cerchia alpina, “Studi etruschi”, vol. VIII, pp. 11-48.

BICKNELL C.

1913 Guida alle incisioni rupestri preistoriche nelle Alpi Marittime Italiane, trad. italiana 1972, Bordighera.

CASINI S.

1994 Bagnolo 1, in Le Pietre degli Dei. Menhir e statue stele dell’età del Rame in Valcamonica e Valtellina, Bergamo, pp. 174-176.

CITTADINI GUALENI T.

198? La riserva naturale delle incisioni rupestri di Ceto, Cimbergo e Paspardo, Breno.

DE LUMLEY H.

1995 Le grandiose et le sacré, Edisud, Aix en Provence.

DE LUMLEY H. – ECHASSOUX A. – MACHU P. – MANO L. – ROMAIN O. – SAULIEU G. – SERRES T.

2000 Datation, attribution culturelle et signification des gravures rupestre d’armes dans les Alpe occidentales au début de la métallurgie (M. Bego, Valcamonica, Haut-Adige, Val d’Aoste et valais), in preatti del IX colloque International “Les Alpes dans l’Antiquité”, la métallurgie dans les Alps occidentale des origines à l’an 1000. Extraction, transformation, commerce, Tende, 93-127.

DE MARINIS R. C.

1994a La datazione dello stile IIIA, in AA.VV., Le pietre degli Dei. Menhir e stele dell’età del Rame in Valcamonica e Valtellina, Bergamo

1994b Pròblemes de chronologie de l’art rupestre du Valcamonica, Notizie Archeologiche Bergomensi, 2, Bergamo, pp. 223-234.

1997 The eneolithic cemetery of Remedello Sotto (BS) and the relative and absolute chronology af the Copper Age in Northern Italy, Notizie Archeologiche Bergomensi, 5, Bergamo, pp. 33-51.

FERRARIO C.

1992 Le figure di oranti schematici nell’arte rupestre della Valcamonica, in “Appunti” 19, p. 41-43.

1994 Nuove cronologie per gli oranti schematici dell’arte rupestre della Valcamonica, Notizie Archeologiche Bergomensi, 2, Bergamo, pp. 223-234.

FOSSATI A.

1992 Alcune rappresentazioni di oranti schematici armati del Bronzo Finale nell’arte rupestre della Valcamonica, “Appunti”, 19, Breno, pp. 45-50.

1994a Le rappresentazioni topografiche, in AA.VV., Le Pietre degli Dei. Menhir e statue stele dell’età del Rame in Valcamonica e Valtellina, Bergamo, pp. 89-91.

1994b Le scene di aratura, in AA.VV., Le Pietre degli Dei. Menhir e statue stele dell’età del Rame in Valcamonica e Valtellina, Bergamo, pp. 131-133.

1994c Ossimo 8, in AA.VV., Le Pietre degli Dei. Menhir e statue stele dell’età del Rame in Valcamonica e Valtellina, Bergamo, pp.189-192.

FRONTINI, P.

1994 Il masso Borno 1, “Notizie Archeologiche Bergomensi”, 2, Bergamo, p. 67-77.

GAVALDO S.

1995 Le raffigurazioni topografiche, in Sansoni U. – Gavaldo S., L’arte rupestre del Pia’ d’Ort, la vicenda di un santuario preistorico alpino, Archivi, Edizioni del Centro, Capo di Ponte, pp. 162-168.

1999 Le raffigurazioni topografiche, in Sansoni U. – Gavaldo S. – Gastaldi C., Simboli sulla roccia, l’arte rupestre della Valtellina centrale dalle armi del bronzo ai segni cristiani, Archivi, Edizioni del Centro, Capo di Ponte, pp. 99-101.

TURCONI C.

1997a The map of Bedolina in the context of the Rock Art of Valcamonica, “TRACCE On line Rock Art Bulletin”, 9

1997b. La mappa di Bedolina nel quadro dell’arte rupestre della Valcamonica, in NAB, 5, pp. 85-113, Bergamo.

(16.368 views in previous TRACCE PHP-Nuke version, 2002-2011)

Brilliant. I hope to join one of your summer school soon. Can you help me register with TRACCE, as the online form appears to not function for me. Is there an alternative route? Signing up for the newsletters is OK, but I can not submit a paper or register to dos so.