This paper investigates a well-known but rare icon from the rock art of the Atacama Desert. It concerns a group of anthropomorphic figures displaying a very specific bird-related element. For that reason Juan Chacama and Gustavo Espinosa speak of ‘hombres-falcónidas’, ‘raptor-men’, to describe this class of anthropomorphic figures. Remarkably, their interpretation seems to be generally ignored by several archaeologists and rock art investigators. This study presents a revaluation of the theory put forward by Juan Chacama and Gustavo Espinosa in 1997.

By Maarten van Hoek

The Avian Staff Bearer

Upgrading a Controversial Icon in Atacama Rock Art

Posted January 2016 – Updated May 2016 (Ariquilda and Conanoxa)

*

Maarten van Hoek – rockart@home.nl

This paper originally is illustrated with 127 photographs, drawings and maps. About half of those illustrations appears in this on-line issue of TRACCE (click any illustration to enlarge, click again or use the back-arrow to go back), while the complete set of illustrations appears in an (also updated – May 2016) PDF that can be downloaded via Academia.

Introduction

This study challenges and refutes the idea – focussing on one specific Andean rock art icon – that it is not scientifically correct to accept biologically impossible representations of biomorphs, especially of combinations and/or conflations of (elements of) zoomorphs and anthropomorphs in rock art. Instead, I argue that, when – for instance – an ancient civilisation depicts a human figure emerging from the head of a bovine (Figure 1), this must be accepted as meaningful and as their reality; not as a scientific biological reality, but as a scientific cultural reality.

Figure 1. Human emerging from the top of the head of a bovine. Part of a frieze at the Temple of Luxor, Egypt. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure 1. Human emerging from the top of the head of a bovine. Part of a frieze at the Temple of Luxor, Egypt. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek.

Click on any illustration in this article to get a larger picture (click the < back arrow [top left] or – in some cases – click on the illustration to return to the article). Click the hyperlinks (in underlined red) to go to other web pages, which will open in a new window (click the X icon [top right] to return to the article).

In this respect this study analyses the distribution and meaning of a specific but still controversial rock art image that is mainly found in the Atacama Desert west of the High Andes of South America. It concerns an anthropomorphic rock art image that is often said to have been derived from well known Tiwanaku iconography, although this study questions this claim. A specific element of this anthropomorphic figure is generally accepted by Chilean archaeologists to represent a kind of garment. Consequently it is often referred to as a ‘skirt’. However, Chilean archaeologist Juan Chacama once claimed that this element symbolised the wings of a bird and that the icon represented a human-bird conflation. Unfortunately his claim does not seem to have been accepted by several Chilean archaeologists.

In this study I offer new evidence and compelling arguments, together with more examples of this type of anthropomorph, which collectively will underpin the theory first put forward by Juan Chacama (and later jointly with Gustavo Espinosa). Unfortunately, some Chilean rock art researchers confine their surveys to only rock art zones in Chile. Therefore, most of the evidence comes from rock art sites in northern Chile, but there is also evidence available across the border. For that reason my Study Area is larger than the Chilean Atacama and includes the deserts of southern Peru as well (which are a continuation of the Atacama).

The extent of the Study Area (Figure 2) is determined by the occurrence of a specific rock art image that I have labelled the Avian Staff Bearer in this analysis. The Study Area is quite large and stretches from San Pedro de Atacama in the Norte Grande of Chile to the Río Majes in southern Peru, a distance of roughly 930 km (via the sites mentioned in this study). As the site that is located farthest inland is found up to 220 km from the coast, the Study Area roughly covers an area of 200.000 km2. The altitudes range from near sea-level to as high as 3500 m O.D., thus excluding the archaeological complex of Tiwanaku (which is at 3864 m and 270 km inland). Although important in this study, Tiwanaku is located outside our Study Area for a reason explained later on.

Figure 2. Map of the Study Area with the sites relevant to this study marked with squares (explained further down in the text). Map © by Maarten van Hoek (updated May 2016), based on Google Earth Relief Maps.

The Study Area mainly consists of the driest desert in the world, the Atacama Desert, which extends further north well into the south of Peru, while the highest areas of the desert mingle with the austere Altiplano of the High Andes. Those two areas are clearly distinguishable in the map of the Study Area (Figure 2).

All altitudes, distances and most UTM coordinates in this study are based on Google Earth (2015: please note that locations may alter in satellite photos of earlier or later dates). The accuracy of those UTM coordinates is explained by stating the feature or the radius in which the rock or site is located. For example, when the Bloque is mentioned the accuracy is 100 %; the rock is (almost) exactly located at the given coordinates. When a village, the area or a radius (e.g. 10 m) is mentioned the accuracy is less than 100%.

It is obvious that rock art is found on natural solid rock surfaces. This seems to be a simple statement, but thus a geoglyph cannot be regarded to be a form of rock art and yet many researches consider geoglyphs to represent true rock art. However, I do not accept geoglyphs to be a form of rock art; it is a form of art arranging small rocks and gravel or sand. Different terms applied for a rock are often equally confusing. Especially in Chilean publications about rock art the Spanish term “Bloque” has often been used. In many cases this term refers without any distinction to (panels on) outcrops as well as to (panels on) loose boulders. This is strange as several Chilean publications also use the term “afloramiento” to specifically refer to rock art panels on outcrops. In this study I will state (whenever possible) whether the rock art is found on an outcrop or on a boulder. When I have access to ‘officially’ published inventories or any other kind of official numbering information, I will use the existing term (mainly ‘Bloque’) to refer to the established numbering of the boulders and/or outcrop panels (for instance: Site Az-29 – Bloque 04B). When I have no information about the numbering of the rocks, I will use the term Boulder or Panel and will use my own numbering (for instance: Boulder ARQn-085).

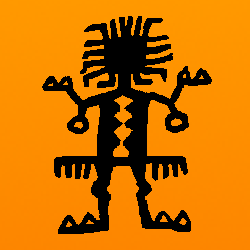

Another problem concerns the description of (variants of) the anthropomorphic figure that is the subject matter of this study. Archaeologists often use different terms to describe some of those figures as well as several related images, which can be very confusing. Based on specific elements those specific anthropomorphic figures have been described as ‘Personaje Frontal de Cabeza Radiada’ or ‘Ser Antropomorfo con Tocado Dentado’ (Frontal Figure with Radiate Head), ‘Personaje Frontal con Cetros / Báculos’ (Front-facing Staff-bearing Deity) and ‘Personaje Sacrificador’ (The Sacrificer). Other terms that are associated with similar rock art figures are ‘Caravanero’, ‘Hombre-cóndor’, ‘Tunupa’, ‘Señor de La Isla’, ‘Icono de Chorrillos’, ‘Señor de los Báculos’ and ‘Ser Mítico’ (La Isla and Chorrillos being place-names in northern Chile). Importantly, one or more graphical elements of all the figures mentioned in this paragraph may be present in one exclusive anthropomorphic figure – the subject of this study. Unfortunately, one of those elements is often too easily accepted to represent a ‘skirt’.

Indira Montt (2002), specifically discussing anthropomorphic (rock art) figures bearing skirts in northern Chile speaks of ‘la imagen antropomorfa con Faldellín’ (the anthropomorphic figure with a ‘skirt’) and she distinguishes four categories of ‘skirts’: 1: ‘Faldellín Segmentado’; 2: ‘Faldellín Segmentado Continuo’; 3: ‘Falda Continua’ and – the focus of this study – 4: ‘Faldellín Desdoblado’. This last category cannot be easily translated with only two words, but the best attempt would be: bisymmetrical skirt.

This study only discusses images that fit into the fourth category; the so-called ‘bisymmetrical skirt’. These are images that comprise only fully frontally depicted anthropomorphic figures with two (mainly horizontally arranged) elements that are emerging from the hip area. In fact, in this study the focus is mainly on only one type of the fourth category of ‘skirts’ (that are not specified by Montt), the elements of which Helena Horta (2004: 66) describes as ‘las flecaduras a la altura de las caderas’ (the fringes at the height of the hips). Indira Montt (2002) moreover argues that those elements represent a sort of pubic covering and that they are the only (!?) piece of clothing that those figures are wearing. However, these purported ‘fringes’ also look very much like the wings of a bird and if so, the figures might even be unclothed.

In this respect Indira Montt (2002: 18) remarks in footnote 10: ‘Este faldellín desdoblado fue llamado por Chacama y Espinoza (1997: 784) “faldellín alado”, siendo considerado por estos autores como la “síntesis de las alas de un ave”,….. which translates as (my additions between [ ]): ‘This ‘Faldellín Desdoblado’ was labelled by Chacama and Espinoza (1997: 784; [2005]) “winged skirt”, because the authors considered it as the “synthesis of the wings of a bird”…. So far so good, but unfortunately Indira Montt continues to say that ‘…. perspectiva que este estudio [Montt 2002] no comparte por tratarse, entre otros argumentos que podrían ser esgrimidos, de un elemento fijado a la figura antropomorfa a la altura de la cintura y no de los hombros’ which, freely translated, reads: ‘I [Montt 2002] do not share their opinion, because, among other arguments that could be put forward, it concerns an element attached to the anthropomorphic figure at the height of the waist, not the shoulders’. Unfortunately she does not mention the ‘other arguments’, which would possibly have been more revealing. For several reasons I disagree with her argument and her consequent conclusion to refute and ignore the interpretation by Chacama an Espinosa. In PART II I will challenge her line of reasoning, reassessing and supporting the theory put forward by Juan Chacama and Gustavo Espinosa.

Indeed, as early as 1997 Chilean archaeologists Juan Chacama and Gustavo Espinosa interpreted those purported ‘pubic’ elements as the wings of a bird. It is even possible that Juan Chacama launched his ideas earlier, in an MS dated 1995. Strangely, their very plausible theory never seems to have been accepted (see Montt 2002: footnote 10) despite the fact that Juan Chacama in a later publication (MS apparently written in 2000 and re-published twice in 2004) convincingly argued again that – also because of the wing-elements – the anthropomorphic figure with the purported ‘pubic fringes’ was strongly bird-related, especially to bird imagery at the petroglyph site of Ariquilda-1, and persuasively expressed bird-symbolism that is related to shamanic beliefs in general. Juan Chacama speaks of ‘hombres-falcónidas’, ‘raptor-men’, to describe this class of anthropomorphic figures. The fact that Chacama, using the term ‘raptor-men’, seems to exclude the possibility that those figures are female, is irrelevant in this study. This study now aims at reinforcing their hypothesis by offering ‘new’ evidence and ‘new’ theories. Also important in this respect is that the issue is put in a broader Andean context.

The Avian Staff Bearer

Juan Chacama regards certain images in Atacama rock art to represent conflations of anthropomorphs and birds, and indeed, several examples are most convincing. Those ornitomorphic images can thus be regarded as therianthropes, or rather, as avianthropes; figures expressing the concept of avianthropy: the power of a human being to transform into a bird, or to gain bird-like characteristics. Several images from Atacama rock art are said to represent conflations of humans and birds, like the (in my opinion less convincing) rock painting of an ‘Hombre-Condór’ at Alero Zurita (Figure 3) in the valley of the Río Loa and at least six (according to Cabello and Gallardo 2014: 16; Fig. 5C) petroglyphs at Tamentica-1 in the Huatacondo Valley (Figure 4). However, in general those images show more birdlike characteristics than anthropomorphic properties. Moreover, those conflations generally have wings emerging from the shoulders, although there are also rock art images of conflations of humans and birds without wings (Aguayo Sepúlveda 2008: Fig. 10).

Figure 3. Rock painting from Alero Zurita, Río Loa, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph in Berenguer 1999: 35.

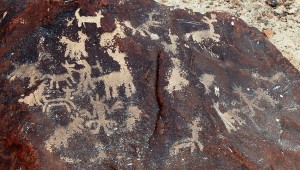

Figure 4. Petroglyphs from Tamentica-1, Chile. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek. Please note that all photos in this study (may) have been digitally improved by the author. Moreover, any error in any of the illustrations is the sole responsibility of the author.

However, the specific human-bird conflation Juan Chacama speaks of is a clearly anthropomorphic figure with extensions from the hip area that indeed much resemble the stylised wings of a bird. In fact, in Andean rock art bird-wings are usually depicted this stylised way. In order to distinguish those anthropomorphic images from the ‘shoulder-wing’ type and from many other differently labelled figures I decided to label this group of human-bird conflations ‘Avian Staff Bearers’ in this study, even though many of such anthropomorphic figures do not necessarily bear staffs (báculos) or sceptres (cetros) or anything else. It must be emphasised however that – in my opinion – the Avian Staff Bearer is not the same figure as the Front-facing Staff-bearing Deity (Personaje Frontal con Cetros / Báculos) mentioned above, which is – for matters of convenience – referred to in this study simply as the Staff Bearer.

Characteristics of the Avian Staff Bearer

Characteristics of the Avian Staff Bearer

There are certain essential characteristics that define the image of the Avian Staff Bearer. Such images predominantly have an anthropomorphic appearance and they always concern standing figures with two arms and two legs, even when – as seems the case in some instances – legs have not been indicated clearly. However, when legs are ‘absent’, the figure may be seated or it may have been depicted with unfinished legs or with minimised legs.

Importantly, Avian Staff Bearers are always depicted fully frontally and symmetrically, which means that they may be mirrored horizontally along their vertical axis, disregarding however occasional minor details that may disturb (often on purpose) this horizontal symmetry. The fingers emerging from the ‘hands’ of the arms are often represented by only two or three lines that quite regularly are arranged parallel to the imaginary ground surface. Most importantly, in this study true Avian Staff Bearers (Types A1 and A2) always show two essential elements: (1) the wing-shaped extensions from the hips and (2) the W-shaped configuration of the arms (or one or two V-shaped arms).

There are however many variations of the Avian Staff Bearer that are mainly determined by secondary characteristics like a head with short radial grooves (the radiant head type). Another variant is the type with short appendages from the head that are arranged in three separate groups of parallel lines. Other examples clearly hold staffs or comparable straight, vertically arranged objects that are held parallel to the body.

In a few cases there is a circle or circular dot attached to the elbow of each V-shaped arm (the nadir of the V). These circular elements are regarded to symbolise ‘trophy’ heads as some images of the Staff Bearer show heads, apparently human, dangling from the elbows (the reason to in general hyphenate the term ‘trophy’ was explained by me earlier [Van Hoek 2010]). This specific feature may be an indication that the (Avian) Staff Bearer sometimes may represent a conflation between the Staff Bearer and the Decapitator or Sacrificer; another important Pan-Andean personage.

Based on those characteristics I will now present a classification and an inventory of the Avian Staff Bearer (Types A1, A2 and A3) and many other possibly related (and often fully frontally depicted) anthropomorphic figures (Types B and C), without pretending however that every Andean rock art image will have been considered.

Avian Staff Bearer Type A1: This type of Avian Staff Bearer has two mandatory properties. It always features the two wing-shaped elements from (near) the hips (the minimum number of downward pointing lines at each element is two). Moreover, the W-shaped arms always hold a ‘staff’ or a comparable object in each hand. However, those objects do not need to be held or even touched by the hands of the Avian Staff Bearer. They may ‘float’ a short distance from the hands/fingers, but they must always involve (more or less) straight objects that are (more or less) vertically arranged, parallel to the body and often to each other. Secondary elements may include a radiant head and/or ‘trophy’ heads from the elbows, all or some of which may be absent or present.

Avian Staff Bearer Type A2: This type always features the two wing-shaped elements from (near) the hips. The arms are always W-shaped. Secondary elements may include a radiant head and/or staffs and/or ‘trophy’ heads from the elbows, all or some of which may be absent or present.

Avian Staff Bearer Type A3: This type always features the two wing-shaped elements from (near) the hips. The arms are not W-shaped, but instead both arms may be drooping, horizontally arranged, raised (the ‘surrendering’ position) or even absent. Avian Staff Bearers of Type 3 in the saluting position (one arm raised; the other drooping) are very rare, but at least one example seems to occur on Outcrop ARQs-073 at Ariquilda-1. Secondary elements may include a radiant head and/or staffs and/or ‘trophy’ heads from the elbows, all or some of which may be absent or present.

Anthropomorph Type B: This type features two elements from (near) the hips that are often horizontally arranged, mostly parallel to the imaginary ground surface. However, these are no specific wing-elements. The elements emerging from the hip area have a (completely) different character, or – when only simple horizontal lines are present – the minimum of two short, downward pointing lines is absent. Therefore, in this study Type B is not classified as a true Avian Staff Bearer. Importantly however, the arms may be W-shaped, although other positions also occur. Arms may even be absent. Other secondary elements may include a radiant head and/or staffs and/or ‘trophy’ heads from the elbows, all or some of which may be absent or present.

Anthropomorph Type C: This type includes all other possibly related anthropomorphic figures. They may involve standing or seated figures without extensions from (near) the hips (and definitely no wing-elements). Their arms are often W-shaped (allowing for other positions as well, though). Arms may even be absent. They may have a radiant head and/or staffs and/or ‘trophy’ heads from elbows.

Archaeological Sites with (Avian) Staff Bearer Imagery

Significantly and surprisingly, the overall number of images of the Avian Staff Bearer proves to be extremely small in Andean rock art. Also the number of archaeological sites where the image has been recorded (on rock surfaces or on artefacts of textile, wood and metal) is rather limited. In this respect I would like to emphasise that not all rock art sites in the Study Area have been fully inventoried and that I definitely have not surveyed all rock art sites in the Study Area. Therefore there may be more sites with images of the Avian Staff Bearer that are unknown (to me), while also known sites may have more images (often hard to recognise due to size, weathering and superimposition). Moreover, rocks once bearing images of the Avian Staff Bearer may have been destroyed (for instance at Tamentica). Nonetheless, with the following inventory of sites with Avian Staff Bearer imagery the minimum distribution of the image will become evident.

This list with archaeological sites with Avian Staff Bearer imagery has arbitrarily been arranged from south to north and the sites have been indicated in Figure 2 with yellow squares that are numbered from 1 to 15. These 15 sites represent fixed images and – except for Site 7, marked with a blue square, which is a geoglyph site – all sites represent rock art sites (as explained earlier I do not regard geoglyphs to be a form of rock art). Also the often mobile artefacts in the Study Area have been arranged on the map from south to north. They have been marked in Figure 2 by green squares and indicated by capital letters B to E. Item A, the archaeological site of Tiwanaku, is located far to the east of the Study Area on the Altiplano of the Andes. For matters of convenience on this study I do not distinguish between the geographical term Tiahuanaco (or Huari) and the cultural term Tiwanaku (or Wari). A number of possibly related rock art sites that are mentioned in this study, appear as red squares in Figure 2. When necessary their location will be indicated from the nearest rock art site (1 to 15) or by Google Earth UTM coordinates, or their names will be mentioned in some of the detail-maps.

Item A: Tiwanaku (Gateway of the Sun – UTM: 534784.67 E – 8169712.62S). The first item is a huge, artificially constructed monument at the archaeological site of Tiwanaku, Bolivia (3864 m O.D. and 270 km inland). Although possibly not at the original location, this ‘Gateway of the Sun’ features one of the best known sculptures of the Staff Bearer. There are more important Tiwanaku-Style sculptures at this site – for instance the Ponce Monolith – and at other Tiwanaku-Style sites on the Altiplano. Yet, none of the sculptured Staff Bearer figures found at Tiwanaku or the Altiplano can be regarded to represent true Avian Staff Bearers. But still their purported relation with the Avian Staff Bearer is said to be relevant and for that reason Tiwanaku comes first in this inventory.

Mobile Item B: Quitor (Pucara de Quitor – UTM: 580534.87 E – 7468312.65 S). Crossing the natural border of the Andes, including enormous stretches of high plains, salt pans, active volcanoes and deep gorges, we arrive in the Atacama Desert. It is said that at one time the influence of Tiwanaku finally reached the desert area around the village of San Pedro de Atacama. In this area several artefacts with imagery of the Staff Bearer have been excavated (López 2007). I only mention one of those artefacts as an example. It is a wooden snuff-tablet from the archaeological site of Quitor-5 (2490 m O.D. and 212 km inland), which was used to inhale hallucinogens from. It features an image that is clearly related to the Staff Bearer at Tiwanaku (Figure 5). But the question – to which I will return later on – is, which element is older: the Quitor artefact or the Tiwanaku sculpture? Importantly, as far as I know, no artefact with an image of the Avian Staff Bearer was ever excavated in the area.

Figure 5. Image on a wooden snuff tablet from Quitor-5, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a drawing in López 2007: 15. The colours have been added arbitrarily to better distinguish several features.

Avian Staff Bearer – Site 1: Vilama Sur (Area – UTM: 585603.00 E – 7473051.00 S). This site is found somewhere along the banks of the Río Vilama, a short distance NE of the village of San Pedro de Atacama (approximately 2570 m O.D. and 218 km inland). Very little has been published about the Avian Staff Bearer at this site and the only published illustration that I could find (Montt 2002: Fig. 21) is too small and too vague to be scientifically useful, while, unfortunately, also an explanatory text is lacking completely. I wrote several Chilean archaeologists to get (literally and metaphorically) a better picture of this petroglyph, but not one scholar answered. In the end I wrote the officials behind the ‘archivo visual proyecto FONDECYT 1000148’, Archivo Nacional de Chile (ARNAD), but in the long run they answered that they ‘could not find’ the original photograph in their archives (sic!).

From the only published photo it seems that the petroglyph is found on a smooth and flat (probably vertical) outcrop. The photo very vaguely shows a wing-element emerging from the left hip; the right-hand element is too faint to be visible (Figure 6). Although the same ambiguity goes for the other properties, it seems that this Avian Staff Bearer is of the A1-Type. Importantly, this river valley is said to have been one of the oldest caravanning routes from the Atacama to the Altiplano by Gonzales Pimentel (2008), who – remarkably – does not mention this specific petroglyph.

Figure 6. Petroglyph on a rock surface along the Río Vilama, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph in Montt 2002: Fig. 21. My drawing is only very sketchy and will no doubt be inaccurate or even incorrect.

North of San Pedro de Atacama are the well known petroglyph complexes of Yerbas Buenas (YB). At Sites YB-1 and YB-2 are several panels with most idiosyncratic anthropomorphic figures (all males?). Most of them appear to be naked and sitting and all have a radiant head with three separate groups of parallel lines. Only one of the ten sitting examples on a large, vertical outcrop panel at Site YB-2 (YB-2, Bloque 1-4 [UTM: 578672.25 E and 7492711.27 S]; sometimes referred to as the ‘Altar de las Budas’; Tamblay 2005; 2006; or as ‘Los Shamanes’), has its arms in the W-shaped position (yellow arrow in Figure 7). At Site YB-1 are several panels with similar figures, (yellow arrows in Figure 8) some of which seem to be standing, but clearly display W-shaped arms, like the examples on outcrop panels Site YB-1, Bloque 7-1 (UTM: 578511.74 E and 7492055.63 S) and YB-1, Bloque 2-9; and on a large boulder at Site YB-1, Bloque 3-1. Further south and SE, on the Piedra de la Coca (Tamblay 2005; 2006) and in the Quebrada de Quesala respectively, similar ‘Budas’ have been reported. However, none of those ‘Buda’ petroglyphs represents an Avian Staff Bearer.

PDF-only -Figure 7. Petroglyph on Panel YB-2, Bloque 1-4 at Yerbas Buenas, Chile. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek. Notice the two very large camelid petroglyphs (heads indicated by blue arrows).

Figure 8. Petroglyphs on Panel YB-1, Bloque 7-1 at Yerbas Buenas, Chile. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek.

Mobile Item C: Chorrillos (Area – UTM: 510392.65 E – 7518628.65 S). Very near the town of Calama on the Río Loa is the archaeological site of Chorrillos (approximately at 2330 m O.D. and 140 km inland). One of the finds in this ancient cemetery was a textile fragment with a very distinct image of the Avian Staff Bearer belonging to the A2-Type (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Image of an Avian Staff Bearer on a textile from Chorrillos Cemetery, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a drawing in Horta 2004: Fig. 6a.

A panel at the rock art site of Yalquincha (Loa Medio – LM01) – located near Chorrillos in a gorge just east of Calama – features a small anthropomorph of about 20 cm in height. Although Bárbara Cases and Indira Montt (2013: Fig. 11d) draw the figure with one arm only, it is V-shaped and holds a vertically arranged straight object, possibly a staff. Unfortunately they do not explain whether this figure concerns a petroglyph or – which is more likely – a rock painting. At the same site there are at least two more rock paintings of anthropomorphic figures that have affinities with the Staff Bearer (Gallardo et al. 2012: Figs 3E and 7E), one with possible extensions from the hip that unfortunately have faded over time (Figure 10).

PDF-only – Figure 10. Rock painting of a possible Staff Bearer on a panel at Yalquincha, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph in https://vimeo.com/58500046 (author unknown).

A petroglyph in the Study Area (similar to the image at LM01, thus possibly also from the Loa area) depicts an anthropomorph of the C-Type with W-shaped arms that are holding a staff each (Sepúlveda and Valenzuela 2012: Fig. 27.7b). Unfortunately, the authors do not state the location of this image.

Avian Staff Bearer – Site 2: Chiuchiu (Area – UTM: 536926.93 E – 7533455.89 S). Further north, a long stretch on the east bank of the Río Loa (on average at 2590 m O.D. and 165 km inland) has numerous boulders detached from the cliffs and outcrops that have rock art (mainly petroglyphs and a much smaller number of rock paintings). Chiuchiu is a most interesting site, but many panels are difficult of access because of the steep slopes that are covered with loose sands (Figure 11). Although no true Avian Staff Bearer image is known at Chiuchiu, there are several related figures, all of the (possibly) A3, B or C Type (illustrated in: Rojas 2005: 27, 28, 30, 53, 73, 78, 93, 98, 117 and 118).

PDF-only – Figure 11. View of the Loa Valley from Panel LA-55 at Chiuchiu, Chile (looking south). Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek. Chilean investigators have indelibly painted the numbers on the petroglyph panels, which should be avoided at all times.

On Bloque LA-72 in the Lucho Sector is a strange anthropomorphic petroglyph, possibly of the A3-Type (Figure 12); notice the position of the arms and the two fingers), while adjacent is Bloque LA-73 with a possible Staff Bearer.

Figure 12. Petroglyph on Panel LA-72 at Chiuchiu, Chile. Drawing © by Maarten van Hoek.

Also many unregistered panels occur at this site. At least three rock paintings with anthropomorphic images of the C-Type occur in the Lucho Sector. One small rock painting is found on an unclassified boulder (Rojas 2005: 74); two others are found on the wall of a shallow, concave rock shelter at a very high position (roughly at 2608 m O.D.). In the Chacras Viejas Sector is one petroglyph of a possible Avian Staff Bearer of the A3-Type (Figure 13). It has W-shaped arms bearing staffs, a radiant head and a small extension from one of the hips (a rudimentary or unfinished wing-element?). In the same sector is a huge boulder with a small petroglyph that possibly represents a Staff Bearer. Another large boulder nearby bears a large petroglyph of an anthropomorph with W-shaped arms, but apparently without legs. Moreover, in all three sectors at Chiuchiu there are several other C-Type petroglyphs, all with W-shaped arms.

PDF-only – Figure 13. Petroglyph on a panel at Chiuchiu, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a drawing in Rojas 2005: 104.

Especially important is the Bloque LA-24 in the Pona Sector of Chiuchiu. The north facing panel (thus facing an impressive row of volcanoes, one of which – San Pedro (Figure 14) – is still active) of this huge boulder features no less than three anthropomorphic petroglyphs of the C-Type. Importantly, although all three are Staff Bearers (Van Hoek 2001), none has the specific wing-element from the hips. However, the most interesting figure has two large snake-like elements emerging form each side of the hip area (Figure 15).

PDF-only – Figure 14. The impressive and still active volcano of San Pedro, looking east from inside the Quinchamale Gorge, Chile. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure 15. Petroglyph on Panel LA-24 at Chiuchiu, Chile. Drawing © by Maarten van Hoek.

Avian Staff Bearer – Site 3: Alto Loa (Area – UTM: 541868.80 E – 7582518.48 S). Further north along the Río Loa (on average 3140 m O.D. and 163 km inland) are several rock art sites with imagery related to the Avian Staff Bearer. This large rock art concentration may have originated because of the presences of the still active volcano of San Pedro, which towers over the region, its 6145 m high summit located only 20 km east of the Loa Valley (see Figure 14). At La Isla a petroglyph of a Staff Bearer with a very complex facial pattern and holding two staff-like objects (one possibly showing feathers; darts?) in his right hand has been reported (Berenguer 1999: 30), while at the same site two petroglyphs of the Staff Bearer occur; one seated on a two-headed camelid (Berenguer 1999: 29). A comparable petroglyph, together with other images of the C-Type, has been recorded at Angostura (Zurita), a rock art site located a little further north on the Río Loa.

A well known rock painting from La Bajada – still further north on the Río Loa – concerns a C-Type of the Avian Staff Bearer (Figure 16). Apparently it is seated, but possibly the legs are missing or only depicted very short (Berenguer 1999: 31). The horizontal bar may symbolise the extensions from the hip or it may represent the (folded?) legs. Importantly it has two ‘trophy’ head elements dangling from its elbows.

Figure 16. Rock painting from La Bajada, Río Loa, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph in Berenguer 1999: 31.

Another rock painting possibly from the La Bajada site features an anthropomorph of the A3-Type. It has two extensions from the hip area and has two raised arms holding diagonally arranged (mirrored) objects (Figure 17).

PDF-only – Figure 17. Rock painting from La Bajada, Río Loa, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph by Ximena Jordán.

PDF-only – Figure 18. Rock painting from Site 2-231, Río Loa, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on an illustration by C. Sinclaire in Montt 2002: Fig. 20.

PDF-only – Figure 19. Rock painting from Site LS-061, Río Loa, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a drawing in Cases and Montt 2013: Fig. 16.

On outcrop Panel 7 of Site 2-Loa 231 is a rock painting of an A2-Type Avian Staff Bearer without the vertically arranged staffs, but with the purported ‘trophy’ heads dangling from the elbows (Figure 18). Unfortunately the head is not visible (Montt 2002: Fig. 20). Site LS-061 in the same area features an image of about 84 cm in height of an A1-Type of the Avian Staff Bearer. Its legs are either very short or, alternatively, it concerns a seated figure (Figure 19). The staffs nearby are slightly undulating (Cases and Montt 2013: Fig. 16) and may be serpent-related. In the same area more related rock art images have been recorded (Gallardo et al. 2012: Fig. 3B, Figs 7C and D).

A petroglyph of a purported seated figure has been recorded from the Toconce River valley (Area – UTM: 578954.43 E – 7533316.33 S), about 40 km east of Chiuchiu (Gallardo et al. 1999: 83). It has W-shaped arms and a radiant head. The figure is much related to similar petroglyphs at Yerbas Buenas. In the same area, at the Incahuasi Inca Site in the Caspana River valley (Aguayo Sepúlveda 2008: Fig. 28) and near Likan (Aguayo Sepúlveda 2008: Fig. 38), a site close to the village of Toconce, are several rock paintings that seem to represent Staff Bearers. In the same area are a rock painting of a possible A3-Type Avian Staff Bearer and a C-Type anthropomorph (Montt 2002: Fig. 6 and Fig. 7 respectively).

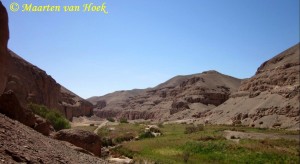

Avian Staff Bearer – Site 4: Tamentica-1 (Bloque 25 – UTM: 481968.90 E – 7681791.54 S). This small rock art site (at 1730 m O.D. and 100 km inland) with a mixture of loose boulders and outcrop panels has sadly been damaged violently very recently. This site is said to have 80 Bloques with altogether 186 panels. Directly opposite Tamentica-1 are the rock art sites of Tamentica-2 and 3. Further east in the Huatacondo Valley (Figure 20) are more rock art sites like Palta Cruz-1 and 2, Chele-1, 2 and 3, San Isidro and Tiquima (locations approximately indicated with red squares in detail-map Figure 21). Further west are the ruins of the prehistoric settlement of Ramaditas where two petroglyph (?) blocks have been built into one of the structures (Van Hoek 2011b).

Figure 20. View of the Huatacondo Valley, Chile, looking NE. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure 21. Map of the Tamentica – Cahuisa area, Chile. Map © by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth (Google Earth Relief Maps).The yellow line indicates the major caravan-route across the Atacama leading to the oasis of Pica (further north; not on map).

Gloria Cabello and Francisco Gallardo (2014) have carried out a study regarding three specific images occurring at Tamentica-1, one of which is called ‘El Ser Antropomorfo con Tocado Dentado’, the ‘Anthropomorphic Being with Dentate Headdress’. They equate this image with ‘El Personaje de los dos cetros’ or ‘El Personaje frontal’. They state that there are ten (or 9 ?) such images at Tamentica (2014: Tabla 1): 4 on Bloque 25; 1 on Bloque 31 and 4 on Bloque 32), five of which show W-shaped arms. Four of those five images can be mirrored symmetrically. Remarkably they also state that only one petroglyph shows the ‘Falledín Desdoblado’, while in fact there are definitely two examples; both of the A2-Type and both appearing close together on Bloque 25 – Panel D; the best (uppermost) example (Figure 22) standing next to two anthropomorphic bird images (see Figure 4). The lowermost example (Figure 23) is rather faint, but is clearly illustrated by Grete Mostny Glaser and Hans Niemeyer Fernández (1983: Fig. 52).

Figure 22. Avian Staff Bearer on Bloque 25 – Panel D at Tamentica-1, Chile. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure 23. Avian Staff Bearer on Bloque 25 – Panel D at Tamentica-1, Chile. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek.

On the same boulder is an anthropomorphic figure with W-shaped arms with dots below each elbow (‘trophy’ heads?) sitting (?) on a vertical bar, and apparently not showing legs (Figure 24). However the vertical bar may represent the (folded) legs or the wing-elements. It is said to be one of the ten (?) Radiant Head images (Cabello and Gallardo 2014), but true linear appendages from the head are not (no longer?) clearly visible at present. This figure (of the C-Type) may be compared with a rock painting from La Bajada (see Figure 16) on the Río Loa (118 km to the SE).

Figure 24. Petroglyph of a seated (?) figure on Bloque 25 – Panel D at Tamentica-1, Chile. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek.

Also on Bloque 25 – Panel D is a very large Radiant Head Anthropomorph, apparently without arms but with three horizontally arranged appendages from each side of the hip (Figure 25). It may be compared with a similar, armless anthropomorphic petroglyph on (outcrop?) Panel ARQn-132 at Ariquilda-1, 152 km north of Tamentica (see Figure 55). Also at Ariquilda-1 is a boulder (exact location unknown) with a similar (anthropomorphic?) petroglyph (unfortunately damaged: parts have flaked off). This example seems to have short W-shaped arms and a similar pattern of short, parallel lines emerging from the hips (see Figure 56).

PDF-only – Figure 25. Petroglyph of an armless figure on Bloque 25 – Panel D at Tamentica-1, Chile. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure 26. Petroglyph of an anthropomorphic (?) figure on Bloque 32 – Panel A at Tamentica-1, Chile. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek.

There are more possibly related figures at Tamentica-1. On Bloque 32 – Panel A is a doubtful anthropomorphic petroglyph (Type-B) with drooping arms and extensions from the hip area (Figure 26).

On Bloque 7 – Panel C is a profusion of images. At the top of this panel, centrally positioned, is a bird petroglyph (Figure 27) with a long serpentine line between the short legs, which is typical for several bird petroglyphs in this area (I will return to this feature). Of possible interest are the wings that are not curved as is often the case but straight (like the wing-elements of Avian Staff Bearers) and instead of short lines representing the feathers, there are rows of small triangles. Similar horizontally arranged lines with rows of triangles (wing-symbolism?) occur on the same panel, as well on Bloque 25 – Panel D. Importantly, to the right of the bird is an anthropomorphic figure that has W-shaped arms, while to its left is a biomorphic figure that has digits from its ‘arms’ and ‘legs’ that are arranged in the same way as in many Avian Staff Bearers (Figure 28).

Figure 27. Petroglyphs of a bird and an anthropomorph on Bloque 7 – Panel C at Tamentica-1, Chile. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek.

PDF-only – Figure 28. Petroglyphs of a bird, an anthropomorph and a biomorph on Bloque 7 – Panel C at Tamentica-1, Chile. Drawing © by Maarten van Hoek.

Mobile Item D: Huatacondo-1 (Ancient settlement – UTM: 469926.00 E – 7678517.00 S). Interestingly, only 12 km west of Tamentica-1 are the well preserved ruins of a prehistoric settlement (Huatacondo-1; at 1375 m O.D. and 88 km inland). In their study of rock art in Chile Grete Mostny Glaser and Hans Niemeyer Fernández include a photo of a gold object that has been found in a tomb very near those ruins (1983: Fig. 111). It proved to represent a Type-A2 Avian Staff Bearer, without the staffs, however (Figure 29).

Figure 29. Gold object representing the Avian Staff Bearer from a tomb near the ancient settlement of Huatacondo-1, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph in Mostny and Niemeyer 1983: Fig. 111.

Avian Staff Bearer – Site 5: Cahuisa-7 (UTM according to Ocampo 2007: 489956.00 E – 7700362.00 S). This petroglyph site, with (only?) one decorated boulder, was discovered during archaeological surveys in the area just north of the Quebrada de Cahuisa, probably in 2005. The site is located at about 2656 m above sea level and about 110 km inland. The panel, probably a large boulder, was found near a west facing rocky cliff of ignimbrite offering good views all around.

Among the images are rows of fully pecked camelids featuring four legs and schematic and linear camelids with two legs. In addition there are anthropomorphic figures associated with camelids, geometric figures like meandering lines, open triangles, two short parallel lines and dots. The surveyors (Ocampo 2007: 301) state that the imagery is reminiscent of that at Tamentica (located only 20 km to the SW) and hence many of the images are said to date from the Archaic or Early Formative Period.

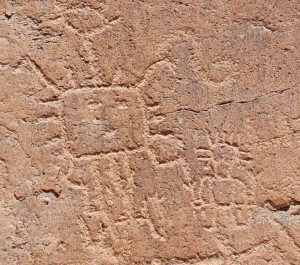

Most important however in the scope of this study are three large petroglyphs representing scavenger-birds. Those birds are said to be associated with a number of camelid images that are however invisible in the photos they provided (Ocampo 2007: 302-303). They moreover interpret the ‘scene’ as scavenger birds prowling on camelids. They further argue that the scene is probably associated with a ritual to protect the camelids from their natural enemies (Ocampo 2007: 302). Yet, the surveyors argue that the camelids, which have been executed in a different technique than the birds, appear to be older. If this is true, then this probably is an instance of a possible ‘superimposed scene’. More importantly, the surveyors failed to notice a most significant characteristic of one of the bird petroglyphs, which I will discuss later on. Indeed, all three petroglyphs depict birds, but one ‘bird’ petroglyph is most idiosyncratic (see Figure 114) and this ‘bird’ will play an important role in the re-evaluation of the Avian Staff Bearer.

Avian Staff Bearer – Site 6: Duplijsa: (Radius 10 m – UTM: 462133.00 E – 7779323.00 S). About 50 m south of the Quebrada Guata-Guata (part of the Parca drainage) and east of the Questa Duplijsa mountain range are two groups of petroglyph boulders (at 1964 m O.D. and 80 km inland). East of Duplijsa are more rock art sites like Quebrada de Imagua, Chunchuja, Ozcuma, Tacaya, (Pucara de) Jamajuga or Cerro Gentilar, Tasma and Noasa. Also a few geoglyph sites are found in this rather high area. Duplijsa may be part of a route from Tarapacá-47 (at 1440 m O.D.) to the area around the village of Mamiña. This route, indicated by a number of geoglyph sites (marked with their altitudes in Figure 30: 1575, 1853, 1733 and 2428), seems to end at the petroglyph site of Pucara de Jamajuga (marked 2865 in Figure 30).

Figure 30. Map of the Duplijsa – Ariquilda area, Chile. Map © by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth (Google Earth Relief Maps).

One group at Duplijsa has four boulders; the other has two. As I have not visited the site, I assume that the images that are relevant to this survey are found on the larger boulder of the second group (labelled Boulder DUP2-001 by me). This boulder has at least four panels with petroglyphs that all have weathered considerably (hence the uncertain nature of my drawings).

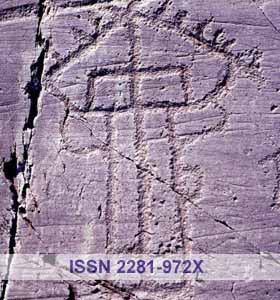

The SE facing and much sloping Panel DUP2-001A (Figure 31) has at least one A3-Type Avian Staff Bearer (Figure 32). However it does not represent the standard Avian Staff Bearer as it has an outlined, circular body with two parallel grooves emerging from both sides, while inside the body is a small cross-like design (a stylised bird?). From the shoulders two wings are held upright and in between is a bird-like head. Remarkably, from the hips two extra wing-elements, which are so characteristic for the Avian Staff Bearer, emerge. The legs/feet are human-like.

PDF-only – Figure 31. Petroglyphs on Panel A of Boulder DUP2-001 at Duplijsa, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph by Vivencias a Color.

Figure 32. The Avian Staff Bearer on Panel A of Boulder DUP2-001 at Duplijsa, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph by Vivencias a Color.

On the vertical, north facing Panel DUP2-001D (Panel C concerns the slightly sloping upper surface and Panel B is a small east facing, vertical panel) are three petroglyphs of Avian Staff Bearers, all of the A3-Type (Figure 33). Two figures have both arms raised (one showing bird-like feet), while the third example has straight, outstretched arms each holding a straight object; staffs? Most interestingly, this last figure has four wing-shaped elements emerging from the hip area and it has bird-like feet.

Figure 33 Avian Staff Bearers on Panel D of Boulder DUP2-001 at Duplijsa, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph by Nativo Tour Chile.

Avian Staff Bearer – Site 7: Cerro Unitas (Geoglyph – UTM: 433705.00 E – 7794034.00 S). Although I do not consider geoglyphs to be a form of rock art, geoglyphs in general and this example in particular are most important in (Andean) rock art studies. The biggest geoglyph at Cerro Unitas (located at 1245 m O.D. on an isolated low hill and 52 km inland) concerns an immense anthropomorphic figure of about 90 m in height (Figure 34). It is oriented to the WSW (azimuth 248 degrees) and is best appreciated from above (Figure 35). It clearly is an Avian Staff Bearer of the B-Type as it has no true wing-shaped elements. The resemblance between this geoglyph and a petroglyph at Ariquilda-1 was already noted by Johan Reinhard as early as 1983.

PDF-only – Figure 34. The geoglyph on Cerro Unitas (within the yellow circle) looking NE towards the Sacred Mountain of Tata Jachura, Chile. Photograph © by Johan Reinhard. Information in his photo added by the author.

PDF-only – Figure 35. The enormous geoglyph on Cerro Unitas, Chile. Photograph based on Google Earth.

The appendages from the head of the geoglyph are not arranged in a radiant way, but more resemble the three arrangements of separate parallel lines found on the heads of several anthropomorphic petroglyphs at Yerbas Buenas (335 km SSE). Interestingly, also at Toro Muerto in southern Peru (510 km NW) is a small anthropomorphic petroglyph that has a radiant head (Figure 36) comparable with the Cerro Unitas geoglyph. However, anthropomorphic petroglyphs with comparable headdresses are also found at Yonán in northern Peru (1735 km NW of Cerro Unitas), so there is always a chance of chance.

PDF-only – Figure 36. Petroglyph on Boulder Cc-005 at Toro Muerto, Peru. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek.

It is often said that the Avian Staff Bearer geoglyph at Cerro Unitas is unique. Although this is true, there are some comparable geoglyphs (without, however, any wing-element) much further NW. Those anthropomorphic geoglyphs are located in the desert around Illapata, SW of the Peruvian town of Palpa and outside our Study Area. Two geoglyphs are found at UTM: 479172.48 E – 8388658.46 S; one of which is incompletely illustrated by Ana Nieves (2007: Fig. 6.23). A single geoglyph [with darts and spear-thrower?] is found at UTM: 481114.00 E – 8386121.00 S. They all wear a strange ‘hat’ (comprising two groups of parallel lines) on a head that has facial features that are comparable with the Cerro Unitas anthropomorph. Most importantly, two figures have W-shaped arms holding one or two staff-like objects (Figure 37). Further NE, also in the Palpa Area, are at least two anthropomorphic petroglyphs with W-shaped arms (one with a staff in each hand), while further SE in the Ingenio Valley is a life-size, but much weathered anthropomorphic petroglyph that resembles the geoglyphs.

PDF-only – Figure 37. Geoglyphs near Palpa, Peru. Photograph based on Google Earth.

PDF-only – Figure 38. Part of the petroglyphs on an outcrop panel at Pachica, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph by Aventura Tarapacá.

Avian Staff Bearer – Site 8: Chusmiza-3 (Radius 30 m – UTM: 478840.13 E and 7821922.36 S). East of Cerro Unitas is the archaeological complex of Tarapacá-47 (at 1440 m) with more than 400 boulders with petroglyphs of which 260 depict anthropomorphs; none depicting, however, any Avian Staff Bearer image or any other example of some related imagery (Núñez 1965; Núñez and Briones 1967-8). Further NE is Pachica (Brant 2008) with – among other panels – an enormous outcrop (at 1695 m O.D.) covered with numerous petroglyphs, the whole looking more like a panel with geoglyphs (Figure 38). But – again – none of the petroglyphs at Pachica is reported to depict the Avian Staff Bearer. Moreover, the area around Tarapacá-47 and Pachica is literally teeming with geoglyphs (only a limited number of geoglyph sites have been marked – with blue squares – in Figure 30). Much further NE is the petroglyph site of Parcollo, also not including any Avian Staff Bearer image (Núñez 1965; exact location of the site unknown to me and therefore most likely incorrectly indicated with 2520 in Figure 30).

Most important is the archaeological complex at Chusmiza, with – according to Flora Vilches Vega (2006) – 178 panels of petroglyphs. The site of Chusmiza-3 (at 3231 m O.D. and 100 km inland) is found in a 240 m deep canyon, only about 30 m south of the Quebrada de Ocharaza. The petroglyph sites of Chusmiza-1 and 2 (Valenzuela Ramírez 2010: Lámina 21) are found in and near two ancient structures further south, on top of a ‘low’ hill and 50 m higher up (Figure 39). Chusmiza-3 comprises a group of petroglyph panels at a lower level, one of which is decorated with one of the most sophisticated rock art images of the Avian Staff Bearer of the A1-Type (see Figure 39). Most important are the two staffs that look like spear throwers (atlatls). I will return to this petroglyph in PART II.

Figure 39. View of the archaeological complex at Chusmiza, Chile. Looking SE. Photograph © by Rolando Ajata. Information in his photo added by the author. The location of Chusmiza-3 is only approximated. Inset in yellow: the Avian Staff Bearer at Chusmiza-3. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph by Gustavo Moscoso.

There are more possibly relevant images at Chusmiza. The upwards facing but much sloping panel of a large boulder at Chusmiza-1 has a small petroglyph of an isolated anthropomorphic radiant head with facial features (Vilches 2006: Fig. 3; Vilches and Cabello 2011: Fig. 6-C11). It looks much like the head of the Avian Staff Bearer at Chusmiza-3 and the head of the geoglyph at Cerro Unitas. Panel 138 has a petroglyph of possibly (part of) a winged figure with a radiant head without facial features (A in Figure 40, which slightly differs from the rendering by Paulina Chávez [Vilches and Cabello 2011: Fig. 3-C9]). Very near it on the same panel is a second, comparable petroglyph – also a radiant head? – again without facial features (B in Figure 40).

PDF-only – Figure 40. Details of some petroglyphs on Panel 138 at Chusmiza, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph in Valenzuela Ramírez 2010: Lámina 22.

Importantly, at Chusmiza is also a petroglyph of an ornitomorphic figure (Vilches and Cabello 2011: 47; Fig. 6-E2) that has wings from the shoulder, but a body that is similar to the body of the Avian Staff Bearer at Chusmiza-3. Similar similarities between bird petroglyphs and images of Avian Staff Bearers have been noted by Juan Chacama also at Ariquilda-1.

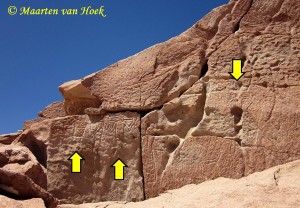

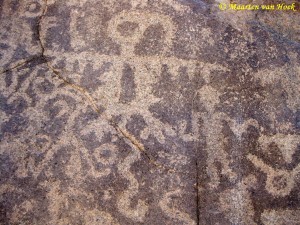

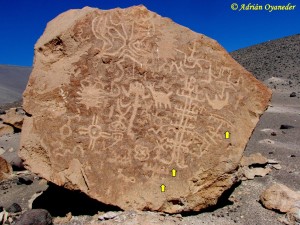

Avian Staff Bearer – Site 9: Ariquilda-1 (Panel ARQn-085 – UTM: 449824.53 E and 7830788.91 S). The petroglyph site of Ariquilda-1 (at about 1720 m O.D. and 73 km inland; see Figure 30) comprises a roughly two kilometre long stretch in the Quebrada de Aroma with numerous decorated cliffs and boulders that are found at both sides of the valley. The pink-red volcanic rock is very suitable to create petroglyphs upon. Yet, the prehistoric manufacturers clearly favoured the more deeply patinated surfaces.

Avian Staff Bearer – Site 9: Ariquilda-1 (Panel ARQn-085 – UTM: 449824.53 E and 7830788.91 S). The petroglyph site of Ariquilda-1 (at about 1720 m O.D. and 73 km inland; see Figure 30) comprises a roughly two kilometre long stretch in the Quebrada de Aroma with numerous decorated cliffs and boulders that are found at both sides of the valley. The pink-red volcanic rock is very suitable to create petroglyphs upon. Yet, the prehistoric manufacturers clearly favoured the more deeply patinated surfaces.

To the west of this petroglyph site and higher up on the Pampa are extensive areas with geoglyphs (at 1805 m O.D.), all fully described by Luis Briones Morales and Juan Chacama Rodriguez (1987). However, none of the geoglyphs represents an Avian Staff Bearer or a related figure. Only Geoglyph 33 in Panel 3 depicts an anthropomorphic figure holding a straight, vertical object, possibly a throwing-spear (Figure 41). Other geoglyph sites in the Atacama also include anthropomorphic figures holding staff-like objects (most likely weapons) but none seems to be related to the Avian Staff Bearer.

PDF-only – Figure 41. Geoglyph 33 in Panel 3 at Altos de Ariquilda Norte, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a drawing by Briones & Chacama 1987.

Unfortunately, a scientific inventory of the nearby petroglyph site of Ariquilda-1 has never been made available for non-academics (and possibly never will), although Juan Chacama confirmed me that there exists such an inventory at the Universidad de Tarapacá at Arica (2011: pers. comm.; see also Van Hoek, M. 2013b). For that reason, regrettably my record of Avian Staff Bearers and related imagery present at Ariquilda-1 will be incomplete. Moreover, I will have to use my own numbering. Panels on the south side are labelled ARQs (Ariquilda-Sur) by me; those on the north side ARQn (Ariquilda-Norte). A map indicating many of the panels in this gorgeous gorge appears in a video that is especially dedicated to Ariquilda-1. This video can be watched by clicking the blue thumbnail-URL below.

To visually support this paper about the Avian Staff Bearer, I have uploaded a video onto YouTube that offers more and different graphical information about Ariquilda than is offered in this publication. The video is in Spanish (please excuse any error) in order to reach especially people in Southern America. You can watch the video using the graphical link below, or, alternatively, you may prefer to click the following link (YouTube) so that the video appears next to the TRACCE publication.

Juan Chacama (2000 MS) states that Ariquilda-1 has 323 Bloques with petroglyphs. A map indicating the official numbering of a few Bloques at Ariquilda-1 is given in Figure 42. However, as explained the term Bloque may involve one boulder or an outcrop comprising of one or (many!) more panels. He moreover states that altogether there are 3623 petroglyphs, of which 855 comprise anthropomorphic images, while at least 176 petroglyphs depict birds. Also remarkable and significant are the many images of ‘solar’ petroglyphs at Ariquilda-1 (unfortunately not counted by Chacama [2000], though).

PDF-only – Figure 42. Map of the rock art site at Ariquilda-1, Chile, showing the official numbers of some of the Bloques. Drawing © by Maarten van Hoek, based on the map in Espinosa 1996: Fig. 2.

Figure 43. Map of the rock art site at Ariquilda-1, Chile, showing the (often much) approximated locations of the petroglyph panels mentioned in this study. Drawing © by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth.

Of the 855 anthropomorphs only 20 are said to show a ‘skirt’ or ‘belt’, but as Chacama does not illustrate all 20 examples, it is impossible to tell exactly how many true Avian Staff Bearers (of the A1, A2 or A3-Type) are present and how many figures are of the B-Type or C-Type. Even Juan Chacama may have missed some petroglyph panels (see for instance Figure 68). Notwithstanding this dearth, I have a pretty good idea what is present at Ariquilda-1, as I have a graphic record of at least 30 panels with (Avian) Staff Bearers and possibly related images. The map of the area (Figure 43) shows the (often much approximated) location of 26 of those panels, indicating with green squares the position of 11 panels with true Avian Staff Bearer petroglyphs. It proves that there is a slight preference for the western part of the valley.

While Juan Chacama (2000: 15) states that there are no staff-like objects depicted in the rock art Ariquilda-1, there are several anthropomorphic petroglyphs that have ‘staffs’. Remarkably, Juan Chacama even illustrates at least four petroglyphs from Ariquilda-1 of anthropomorphs that clearly hold ‘staffs’ (Figure 44A, B, C and E). Several of those ‘staffs’ look more like ‘clubs’. At least one of the Avian Staff Bearer petroglyphs at Ariquilda-1 holds similar club-like objects (see Figure 68).

PDF-only – Figure 44. Some of the Staff Bearer petroglyphs at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on drawings in Chacama 2005: Figs 2, 4 and 10.

In his paper (2000) he moreover illustrates several petroglyphs that I could not trace in any of the graphic information that I have available. Therefore their locations are unknown to me. Of interest is the petroglyph illustrated in Figure 45A. The figure clearly has W-shaped arms with possible ‘trophy’ head extensions. The elements that emerge from the hips are not wings but S-shaped devices. Also an anthropomorphic image of an Avian Staff Bearer on a loincloth from Topater-1 near Calama features similar S-shaped elements from the hips (Horta 2004: Fig. 6b). I would like to argue here that they possibly symbolise ‘staffs’, because an anthropomorphic petroglyph at Tamentica-1 holds similar S-shaped objects in its V-shaped (not W-shaped) arms. However, Juan Chacama illustrates another Avian Staff Bearer (of the C-Type) which holds objects that are only slightly S-shaped (Figure 45C). Thus they could equally symbolise (transformed?) spear-thrower devices.

Figure 45. Some of the Avian Staff Bearer petroglyphs at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on drawings in Chacama 2005: Figs 2, 4 and 10.

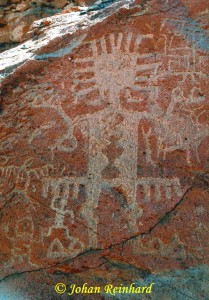

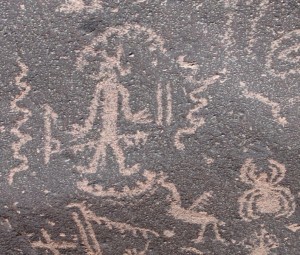

Panel ARQn-085: Indeed, perhaps the best known rock art site regarding the Avian Staff Bearer is Ariquilda-1, and it certainly is the site with one of the most impressive images of the Avian Staff Bearer. Probably for that reason the hypotheses put forward by Juan Chacama and Gustavo Espinosa are mainly based on this image and the many other related figures at this site. There will be probably (many) more Avian Staff Bearers and related figures at Ariquilda-1, but they often are hard to recognise being much weathered, indistinguishable because of superimpositions or because of unfavourable lighting conditions. Some petroglyphs at this site have also been altered or added in recent times, although – fortunately – vandalism is almost absent at this site (but it does occur).

This ‘best’ example of the Avian Staff Bearer (Figure 46) is found on the north bank near the west end of the gorge (approximate location indicated in Figure 43). It is found on a projecting outcrop (Panel ARQn-085) with a flat surface that rather steeply slopes in some southerly direction (Figure 47). All views to the east are completely blocked. Probably because of the superimpositions on this panel and the weathered nature, the drawings of this petroglyph published by several authors may differ in detail. As it bears no ‘staffs’ and as there are no vertically arranged objects in its immediate neighbourhood, it clearly belongs to Type-A2. The figure (Figure 48) measures approximately 125 cm in height (Reinhard 1988: Fig. 36) and thus probably is one of the largest Avian Staff Bearer petroglyphs of the Study Area (I have not measured most of the Avian Staff Bearer petroglyphs in the Study Area). Notice the upward pointing triangular ‘fingers’ and ‘toes’; features that occur in other (Avian Staff Bearer) petroglyphs at Ariquilda and in the rest of the Study Area.

Figure 46. The Avian Staff Bearer on Panel ARQn-085 at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Photograph © by Johan Reinhard (digitally enhanced by the author).

Figure 47. The Avian Staff Bearer on Panel ARQn-085 at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek.

PDF-only – Figure 48. The Avian Staff Bearer on Panel ARQn-085 at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek.

Although Juan Chacama does not include facial features in his illustrations of this figure, it seems that these features (rectangular eyes and mouth) are present after all, although indeed they are only very faintly visible. The same goes for the circular appendages of the elbows. The one dangling from its right-hand elbow is clearly visible; the other is much more obscured.

Panel ARQn-081: A short distance SE of Panel ARQn-085 is Panel ARQn-081 with a possible example of the Type-A3 Avian Staff Bearer. It is much weathered.

Panels ARQn-089 and 168: A short distance NW of Panel ARQn-085 is the heavily decorated Panel ARQn-089. It has a possible example of the Type-A3 Avian Staff Bearer (Figure 49). It has triangles possibly representing ‘feathers’. Also its arms/hands are formed by triangles. Immediately east of this large panel is a much smaller outcrop (Panel ARQn-168) with an indistinct petroglyph of an ‘avianthrope’.

PDF-only – Figure 49. A possible Avian Staff Bearer on Panel ARQn-089 at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek.

Panel ARQn-108: This small panel (possibly part of Bloque 233) has a long-beaked profile-bird petroglyph and some other images, but also a Type-C anthropomorph with W-shaped arms and the typical finger-position of the Avian Staff Bearer. The head is much weathered (yellow arrow in Figure 50). To the left is a panel with a solar head petroglyph with facial features (blue arrow in Figure 50).

Figure 50. A possible Avian Staff Bearer on Panel ARQn-108 at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Photograph © by Coen Wubbels (digitally enhanced by the author). Information in his photo added by the author.

Panels ARQn-110 and 111: On Panel ARQn-111 (part of Bloque 233) is an anthropomorphic figure of the C-Type (Figure 51; yellow arrow in Figure 52). It has a radiant head, W-shaped arms with a ‘trophy-head-symbol’ dangling from each elbow. It does not have wing-elements and neither does hold staffs, but directly to its left (right for the observer) are two vertically arranged and parallel grooves that could represent the staffs. To the left of the ‘staffs’ is a possible Radiant Head petroglyph (green arrow in Figure 52). It seems to have been obliterated (on purpose?). On adjacent Panel ARQn-110 is a more distinct Radiant Head petroglyph, without facial features however (red arrow in Figure 52). It seems to have two ‘V-shaped’ ‘arms’ emerging from the head, one possibly holding a ‘staff’.

Figure 51. A possible Avian Staff Bearer on Panel ARQn-111 at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Drawing © by Maarten van Hoek.

PDF-only – Figure 52. A possible Avian Staff Bearer on Panel ARQn-111 at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Photograph © by Coen Wubbels (digitally enhanced by the author). Information in his photo added by the author.

Panel ARQn-115: Only a couple of metres to the NW is outcrop Panel ARQn-115 with several faded images including two anthropomorphs, one with W-shaped arms.

Panel ARQn-123: On the east side of the promontory and a short distance east of Bloque 265 is Panel ARQn-123 with an Avian Staff Bearer of the A3-Type (Figure 53). It clearly has wing-elements from the hip, but its arms are drooping. It has a simple circular head without appendages.

PDF-only – Figure 53. An Avian Staff Bearer on Panel ARQn-123 at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek.

Panels ARQn-125 and 129: A short distance further east is a much fragmented outcrop. On Panel ARQn-125 is a small Avian Staff Bearer of the A3-Type (Figure 54). It clearly has wing-elements from the hip, and again its arms are drooping. It has a simple circular head with three short, straight appendages. To its left might be another, much smaller Avian Staff Bearer petroglyph. On Panel ARQn-129 to the left is a very simple small petroglyph of a C-Type anthropomorph with W-shaped arms.

Figure 54. An Avian Staff Bearer on Panel ARQn-125 at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Photograph © by Johan Reinhard (digitally enhanced by the author). Information in his photo added by the author.

Panel ARQn-132: Further east is outcrop (?) Panel ARQn-132, which has a large number of images, including one small anthropomorph depicted in profile but with W-shaped arms, each holding a straight object. On the same panel is the large, arm-less anthropomorphic figure with rectangular extensions from its hips (Figure 55). A somehow comparable petroglyph occurs on a large boulder, probably at ARQn (Figure 56).

PDF-only – Figure 55. Petroglyph on Panel ARQn-132 at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph in Von Däniken 1997: Fig. 89.

PDF-only – Figure 56. Petroglyph on a panel at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph by Horacio Larrain Barros in: eco-antropologia blogspot.

Panels ARQn-141 and 144: Still further east and high up the cliff is a very large, fragmented almost vertical cliff with many petroglyphs. Panel ARQn-144 of this large outcrop has a rather large petroglyph of an Avian Staff Bearer of the A1-Type. It has wings from the hip or belly area, but the feathers are hardly visible (Figure 57). It holds a small, straight object in each hand (‘staffs’?) and the arms are somewhat W-shaped. Its head has a headdress that is comparable with elements decorating several abstract pipette-designs (perhaps depicting abstracted anthropomorphs?) that mainly are found at the south side of the valley. The west part of the vertical outcrop (Panel ARQn-141) has an anthropomorphic figure with W-shaped arms (an unfinished Avian Staff Bearer? – see video).

Figure 57. Avian Staff Bearer on Panel ARQn-144 at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek.

Panel ARQn-163: Located in the far eastern part of the gorge on a SE facing outcrop and about 5 m above ground level is a large outcrop (Panel ARQn-163) that has only a few petroglyphs. At the extreme end of the panel is a rare four-winged Avian Staff Bearer of the A3-Type. The petroglyph clearly shows an anthropomorphic figure with arms in the ‘surrendering’ position that simultaneously are wing-elements, although the ‘hands’ are indicated as well (see Figure 45F). But also from the hips wing-elements emerge. The feet are human-like.

The four-winged Avian Staff Bearer figure is repeated at least two times at Ariquilda-1. One possible example will be discussed at the south side of the valley (Panel ARQs-039), while Juan Chacama illustrates another four-winged petroglyph from an unknown location at Ariquilda-1 see (Figure 45D) although the wing-elements from the hip are different and may be compared with the strange image at Chiuchiu (see Figure 12). This Avian Staff Bearer has a long line between the legs; indicating male sex?

Panel ARQn-155: Located about 25 m east of Panel ARQn-163 is a very large decorated outcrop panel located about two meters above ground level. Apparently it has been damaged by high water torrents like several other panels at low levels. It has one faint anthropomorphic figure with W-shaped arms. We now cross the Quebrada de Aroma to explore the south side.

Panel ARQs-007: Almost opposite Panel ARQn-155 and thus on the south bank of the valley is a series of large, rectangular outcrops with numerous petroglyphs. Many of those panels have weathered considerably and most figures are faint and can only be distinguished with perfect lighting. It is certain that I missed quite a lot of the panels/petroglyphs. On Panel ARQs-007 is an Avian Staff Bearer of the A2-Type, while further west on the same panel may be an unfinished Avian Staff Bearer (also of the A2-Type?). At the extreme east are the faint remains of another possible Avian Staff Bearer of the A2-Type.

Panel ARQs-024A: The steeply sloping surface of a large boulder (Figure 57A) has numerous petroglyphs, mainly of zoomorphs (camelids). One very small anthropomorph in the lower right-hand corner, which definitely represents an Avian Staff Bearer of the A3-Type, seems to hold a large camelid on leash (scene framed in Figure 57B). On the panel are also three unconventional anthropomorphic figures (two larger examples and one smaller; indicated with blue arrows in Figure 57A) with ‘peculiar’ appendages from the body. Those appendages are vertically arranged and parallel to each other. Those anthropomorphs of the B-Type may be related to the Avian Staff Bearer although they do not seem to have arms. Indicated by a yellow arrow is another ‘strange’ winged figure.

Figure 57A. Boulder ARQs-024 at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Photograph © by Chileresponsibleadventure.com (Mistico Outdoors), digitally enhanced by the author. Courtesy of Sr. Billy Morales, Iquique, Chile. The framed area is enlarged in Figure 57B. Information in his photo added by the author.

PDF-only – Figure 57B. Detail of Panel ARQs-024A at Ariquilda-1, Chile, showing the very small Avian Staff Bearer with a camelid on leash. Photograph © by Chileresponsibleadventure.com (Mistico Outdoors), digitally enhanced by the author. Courtesy of Sr. Billy Morales, Iquique, Chile.

Panel ARQs-027: Outcrop Panel ARQs-027 (Bloque 69, Panel 1) west of ARQs-024 may have two unfinished (?) anthropomorphic figures; one possibly of the A3-Type Avian Staff Bearer.

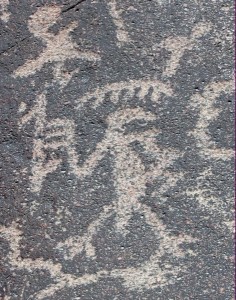

Panel ARQs-028: On adjacent Outcrop Panel ARQs-028 (Bloque 69, Panel 2) is a petroglyph of an avianthrope that (unfortunately) is superimposed (on or by?) camelid petroglyphs and therefore less distinct. Importantly, the avianthrope has a human head, but has its wings from the shoulder. It is flanked by two possible Staff Bearers (Figure 58). A little higher on the same panel is a definite Type-A3 Avian Staff Bearer with drooping arms and ill-defined legs (Figure 59). On adjacent Panel ARQs-30 (Bloque 69, Panel 3) is a much weathered petroglyph of a large anthropomorph that may be related to the Staff Bearer.

Figure 58. Petroglyphs on Panel ARQs-028 at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Photograph and drawing © by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure 59. Petroglyphs on Panel ARQs-028 at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Photograph and drawing © by Maarten van Hoek.

Panel ARQs-176: A small outcrop (Panel ARQs-176) about 2 m above Panel ARQs-034 (Bloque 70) has an unambiguous example of an Avian Staff Bearer of the A2-Type (Figure 60). The figure seems to have both its arms raised. This panel overlooks a small (mostly dry) waterfall that is located immediately to its west. High above Panel ARQs-176 is another panel with one of the most intricate solar symbols that I have seen at Ariquilda-1.

Figure 60. Petroglyphs on Panel ARQs-176 at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Photograph © by Johan Reinhard (digitally enhanced by the author). Information in his photo added by the author.

Panel ARQs-039B: West of the ‘waterfall’ is a large, east facing and much fragmented outcrop cliff, with several panels that are covered with petroglyphs. One (Panel ARQs-037) has a large petroglyph of a raptor (Figure 61). Lower down is vertical Panel ARQs-039B, which has probably the smallest petroglyph of a Type-A3 Avian Staff Bearer at Ariquilda-1 (indicated with a yellow arrow in Figure 62). Its fully pecked circular head has a few short rays. It has wing-elements from the hips and it may even have wing-elements from the shoulders as well (Figure 63). Interestingly, a possibly four-winged biomorph occurs on Panel ARQs-039A, which is located directly above Panel ARQs-039B (indicated with a green arrow in Figure 62).

PDF-only – Figure 61. Condor petroglyph (black) on Panel ARQs-037 (black square) at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Photograph and drawing © by Maarten van Hoek. Red squares: Panels ARQs-039 to 042 (see Figure 62).

PDF-only – Figure 62. Panels ARQs-039to 042 at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek.

Figure 63. Avian Staff Bearer on Panel ARQs-039B at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph by Carlos Aracena. My sketch of this petroglyph may well be inaccurate or incorrect.

Panel ARQs-040: Directly to the left of Panel ARQs-039A is Panel ARQs-040. Among the images (one possibly depicting a turtle) is a large, rectangular face or mask petroglyph with small dots for eyes and mouth and groups of linear appendages (thus much resembling the ‘solar’ heads of several Avian Staff Bearers). To its right is a very small image of an Avian Staff Bearer of the A2-Type (indicated with a red arrow in Figure 62). Although it does not hold staffs, it proves to have possible ‘trophy-head-elements’ dangling from the elbows (Figure 64). On adjacent Panel ARQs-041 may be a petroglyph of an avianthrope.

Figure 64. Petroglyphs on Panel ARQs-040 at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek.

Panel ARQs-050: Two small petroglyphs of possible Staff-Bearers occur on Panel ARQs-050, but the objects they carry are very small and are not held vertically (visible in the video at 2.36 minutes).

Panel ARQs-054: A small boulder at ground level has a petroglyph of an anthropomorph with W-shaped arms emerging from its radiant head.

Panel ARQs-076: At the west end of the gorge and almost opposite Panel ARQn-085 is a large, much fragmented, vertical outcrop cliff. On Panel ARQs-076 is a Type-A3 Avian Staff Bearer in the ‘saluting’ position (indicated in the video at 2.00 minutes).

Panels with Unknown Location. More petroglyphs of Staff-Bearers and Avian Staff Bearers were noted at Ariquilda-1 by other visitors. Felipe Pedro Lázaro made a photo of a possible Type-A1 Avian Staff Bearer at a location at Ariquilda-1 that is unknown to me (Figure 65). The straight vertical petroglyph next to this figure may represent a ‘staff’. The triangular wing-elements are repeated at the Type-A3 Avian Staff Bearer on Panel ARQn-089 (see Figure 49). Johan Reinhard made a photo of petroglyph Panel ARQs-188 featuring no less than three Staff-Bearers of the C-Type close together, each with elaborate headdress (Figure 66). Another Staff-Bearer petroglyph of the C-Type with one longer and a shorter ‘staff’ occurs at a location at Ariquilda-1 that is also unknown to me (Figure 67).

Figure 65. Avian Staff Bearer on a rock panel at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph by Felipe Pedro Lázaro.

PDF-only – Figure 66. Avian Staff Bearer on a rock panel at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Photograph © by Johan Reinhard (digitally enhanced by the author).

PDF-only – Figure 67. Petroglyph of a C-Type of a Staff Bearer petroglyph at Ariquilda 1, Chile. Photograph © by Dinko Kosanovic of Desierto Verde Expediciones.

Finally, a very distinct petroglyph of a Type-A1 Avian Staff Bearer was photographed by Carlos Aracena at a location at Ariquilda-1, also unknown to me. The fully pecked figure clearly holds a club-like ‘staff’ in his left hand (Figure 68). See update (May 2016) at the end of the paper.

Figure 68. Avian Staff Bearer on a panel at Ariquilda-1, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph by Carlos Aracena. My sketch of this petroglyph may well be inaccurate or incorrect.

Conclusive Remarks about Ariquilda-1. It proves that Ariquilda-1 no doubt is the site where the largest number of Avian Staff Bearers and related images are found. There must have been a specific rationale for this enormous concentration at this spot, which I will attempt to explain further on. Interestingly, the petroglyphs of Avian Staff Bearers at Ariquilda-1 vary enormously in magnitude, as if size did not matter. Also the location and orientation of the panels with Avian Staff Bearers does not show any preference. The largest example, on Panel ARQn-085, is found at the west end on a south sloping surface, with views that are completely blocked to the north and east. The two smallest examples, on Panels ARQs-039 and 040, are found in a more central part of the valley on east facing panels and have only limited views of the nearby valley floor. Views to the east are completely blocked. Other panels with Avian Staff Bearers or related imagery face NW, SE, NE and SW.

Mobile Item E: Pisagua D (Area – UTM: 375010.40 E and 7833927.53 S). On a textile bag, said to be found at Cemetery D near the coastal town of Pisagua (exact location unknown to me: 500 m O.D.? and 4 km inland?), is a very clear image of an A2-Type of the Avian Staff Bearer that is not holding staffs (Figure 69). Another textile bag shows another related image from (a different?) cemetery in the same area (Gallardo et al. 2012: Fig. 7B).

Figure 69. Avian Staff Bearer on a textile from Pisagua-D Cemetery, Chile. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph in Montt 2002: Fig. 24.